An estimated 1.2 million Americans are living with HIV, human immunodeficiency virus, a virus that attacks the body’s CD4 cells which help to fight off infections (CD4 cells), making individuals more susceptible to various infections, diseases, and cancers.1, 2, 3 If left untreated, the virus progresses, destroying individuals’ immune systems over time, leading to significant health declines and the onset of AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome).3 Once HIV has advanced to the stage of AIDS, the estimated survival rate is 3 years, resulting in nearly 20,000 deaths among adults and adolescents living with the disease in 2022.1, 3 Although no cure exists, various advancements in modern medicine, such as PrEP, PEP, and ART therapy, can significantly reduce the transmission of the disease and lower the viral load of HIV in one’s blood to an undetectable level, allowing individuals living with HIV to live long and healthy lives.3, 4

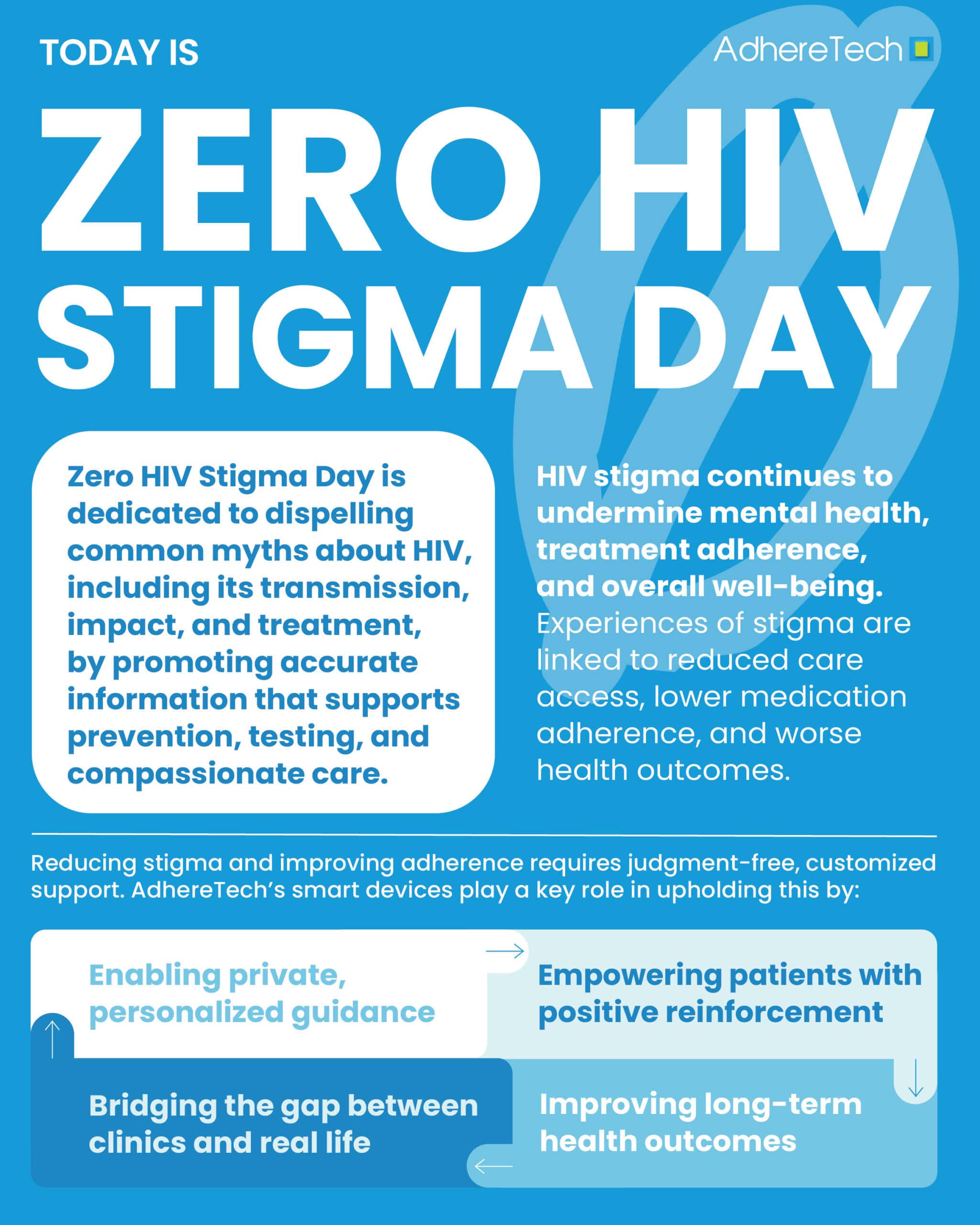

Despite such advancements, the stigma and discrimination surrounding HIV remains a pressing issue that can significantly impact one’s quality of life and their treatment outcomes.5 The negative societal perception of HIV can result in “self-stigma,” where individuals living with the disease take on the negative perceptions and stereotypes others have of those living with HIV and begin to internalize them.6 This can result in psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and feelings of shame, all of which can detrimentally impact an individual’s quality of life and adherence to their prescribed medication regimens.5, 7

Unfortunately, stigma in the healthcare setting is not uncommon either, which can reinforce an individual’s negative self perception while simultaneously resulting in a series of outcomes detrimental to one’s physical health.5 Research indicates that experiences of HIV-stigma can result in less access to treatment, lower utilization of HIV services, and poor medication adherence, all of which contribute to worsened health outcomes.5

Consequently, Zero HIV Stigma Day is observed annually on July 21st, a day dedicated to facilitating conversations regarding HIV, debunking misconceptions, and emphasizing the importance of testing and treatment.8 Together, we can begin to dismantle the stigma and discrimination associated with HIV, ensuring that all individuals living with HIV receive the treatment and support they deserve in order to live long, healthy lives.

The HIV Epidemic: An Overview

On June 5th, 1981, the CDC published an article discussing an unusual five cases of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) among gay men residing in Los Angeles, who previously, had been considered perfectly healthy.9 Confusion grew as all these men exhibited additional signs of various infections and significantly weakened immune systems, resulting in two of them passing away before the report’s publication, and the other shortly after.9

On this same day, the CDC was informed of a cluster of cases of Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS), a rare and aggressive form of cancer, among gay men in New York and California.9 Both PCP and KS are associated with weakened immune system functioning, and the individuals being diagnosed with these conditions, presented with severe immunodeficiencies, only surviving a few months after their symptoms presented.9 In an effort to identify the risk factors and a definition for this unknown syndrome, the CDC established a task force a few days afterwards.9

Unfortunately, with these symptoms first being identified predominantly among the gay population, who were already experiencing a significant amount of discrimination and stigma during this time, stigma surrounding this unknown syndrome spiraled, with the press, and consequently society, largely equating its acquisition with being gay.9,10

However, throughout the 1980s additional cases continued to emerge of what would become known as Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), with women and children also contracting the disease.7 As additional cases emerged, it became evident that the disease seemed to disproportionately impact marginalized communities, such as gay men, individuals struggling with drug injection (needle-based), sex workers, those receiving blood transfusions, etc.10 As the number of cases and populations impacted continued to grow, misinformation ran rampant, with the public growing concerned they could acquire the disease through everyday contact with those diagnosed. For example, in 1985,at the age of 13, Ryan White was diagnosed with AIDS after receiving a blood transfusion. Public hysteria contributed to Ryan’s school district initially refusing to let him return to school, despite the CDC ruling out casual contact, food, water, air, or surfaces as possible mechanisms of transmission of the disease.9,10 Despite medical experts speaking at his court case, it took about a year and a half for Ryan to be able to return to school, and even then stigma surrounding his diagnosis persisted, with people insinuating Ryan must have been gay or done something wrong to develop the disease.9 Negative public perception was widespread, with with a poll from the Los Angeles Times finding that the majority of Americans believed people living with AIDS should be quarantined from the rest of society, this same year.9

By 1986, the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses announced that the virus which causes AIDS was to be officially known as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV).9 After this, treatment advances began to emerge. In 1987, Azidothymidine (AZT), now referred to as zidovudine, was developed to prolong the life of those living with HIV and prevent transmission for HIV from mother to child when taken during pregnancy, however, it was only considered moderately efficacious.10 By the mid 1990s, more effective combination therapies emerged, but these regimens frequently required consuming 20+ pills daily and a series of unpleasant side effects.8

A decade later in 1996, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) became available and was established as the standard of care for HIV in America, reducing AIDS related deaths by 47% in 1997.10 While the initial regimen required a vast combination of drugs, as time continued, combination pills continued to be developed, simplifying the dosing regimen to what it is today, which can be as little as once daily dosing.10 Testing for HIV continued to improve, from the first home testing kit approved in 1996 and the first rapid test approved in 2002.10

In 2012, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), was developed, which is a prescription medication that is highly effective in preventing the risk of acquiring HIV for those a risk when taken as prescribed.10 As of 2024, lenacapvir, a long-acting injectable administered twice a year for protection against HIV was named the breakthrough drug of the year.11 Prevention remains the predominant strategy for reducing the transmission and immunodeficiency complications associated with HIV, and while no cure exists, the advancement of new medications has allowed those living with HIV to live long, healthy lives.4

HIV: Stigma in the Modern Day

Despite efforts to raise awareness and dismantle the stigma surrounding HIV and AIDS, public health messages occurring in the 1990s and early 2000s continued to imply that the disease’s development was rooted in societally-unacceptable personal behaviors, such as promiscuity and sharing needles.10 Such messages had a lasting, negative effect, continuing to fuel blame and further marginalize communities disproportionately impacted by HIV, which has translated into a higher risk of being discriminated in medical care, housing, and employment opportunities.10

In 2021, throughout the world, 21% of people living with HIV reported being denied health care within the past 12 months.12 Moreover, there are 47 countries that still maintain travel restrictions for people living with HIV, resulting in individuals residing in or attempting to travel to these regions often being placed at higher risk of being subject to stigma, discrimination, and violence.12

Recent reports indicate, that within the United States, only 32% and 33% of people report being comfortable working with a coworker living with HIV or interacting with a teacher living with HIV, and uncomfortably increased slightly from 2022 to 2023, underscoring the persistence of such stigma.13 Another report found that 90% of Americans believed HIV stigma still existed as of 2023, with nearly 40% of Americans still believing HIV predominantly impacted members of the LGBTQ+ community.14 Unfortunately, many individuals living with HIV still report experiencing high rates of stigma and discrimination, in dating, sex, as well as accessing and receiving healthcare services, all of which can profoundly impact their adherence to their antiretroviral medication regimens.15, 16

A cross-sectional study of 120 women found a significant correlation between perceived HIV stigma and adherence to their HIV medication regimen (ARV) (p = 0.045; OR: 2.274), 62.7% of women with low HIV stigma were adherent to their ARV regimens when compared to women with higher stigma, where only 32.8% were classified as adherent.17 Another study of 120 youth receiving HIV treatment found that internalized HIV stigma was associated with lower likelihood of ART adherence (p = 0.008; OR: 0.64).18 Moreover, research has shown that internalized HIV stigma was significantly associated with lower levels of adherence motivation (β = −0.52, p < .001) and lower levels of adherence-related behavioral skills (β = −0.72, p = .002).18

Additional research reinforces that HIV stigma is negatively correlated with adherence (r = -0.17, p < 0.05), in addition to increased stress (r = 0.25, p < 0.01).19 Moreover, HIV-related stress was correlated with poorer adherence (r = -0.22, p <0.01), suggesting stigma can have both direct and indirect impacts on negative adherence outcomes.19 This proves particularly concerning, given that this particular study reported that individuals who experienced 4 or more stigmatizing experiences had adherence levels that placed them at considerable risk for developing treatment resistance.19 Consequently, the research overwhelmingly suggests that HIV stigma significantly reduces medication adherence, which can lead to disease progression or treatment resistance, both of which worsen overall health outcomes.

Myth-Busting: Debunking Widespread Misinformation and Misconceptions

In honor of Zero HIV Stigma Day, it is critical to begin informing the public with the facts regarding HIV, and dismantle the widespread public misconceptions of the disease.

- HIV Can be Contracted from Touching or Being Around Someone Living with the Disease

- The CDC has confirmed that the only possible mechanisms of HIV transmission are through particular body fluids such as “blood, semen, vaginal fluid, rectal fluid, or breast milk.”20

- People Living with HIV Should Not Have Children

- As long as HIV-positive pregnant women adhere to life-saving HIV treatments throughout their pregnancy and during breastfeeding, their children can be HIV-free.20

- HIV Only Affects Members of the LGBTQ+ Community

- The first documented cases of AIDS in America in the 1980s were among men who identified as gay or men who were intimate with other men.20 While HIV disproportionately impacts individuals of the LGBTQ+ community, it is by no means exclusive.20 In fact, in 2022, 22% of new HIV diagnoses were attributed to heterosexual contact.1

- Adherence is Not a Challenge for Patients Diagnosed with HIV

- While adherence is typically defined at an 80% threshold, adherence to ART regimens (for HIV) requires a minimum threshold of at least 85% to ensure the medications efficacy.21 Why? Nonadherence, classified as anything below 85%, can severely compromise the effectiveness of treatment and can prevent virus suppression, which can result in HIV drug resistance, contributing to disease progression and poorer long-term health outcomes.21 A series of societal, personal, and healthcare related factors, can make achieving such stringent adherence requirements exceptionally challenging for those living with HIV, regardless of the consequences associated with nonadherence.

- There Are No Symptoms of HIV Until the Disease Progresses into AIDS

- Although many people are unaware of the early symptoms of HIV until it progresses into AIDS, many (but not all) individuals experience flu-like symptoms.22 Research suggests up to 80% of individuals with HIV experience such symptoms, which most commonly include fever, sore throat, and/or body rashes.23 However, these symptoms usually persist for an average of 1-2 weeks after the infection period, and then disappear until the disease has significantly progressed and damaged one’s immune systems, which may take up to 10 years.23 While the incubation period symptoms associated with HIV are commonly caused by an array of other viruses and conditions, if someone experiences several of these symptoms and believes they may have been at risk of HIV within the prior few weeks, testing is essential to ensure timely intervention.23

- For individuals at risk of exposure to HIV, routine testing is essential, regardless of symptom presence.

How Can We Reduce the Stigma and Improve Adherence?

Reducing HIV stigma and improving medication adherence not only requires dismantling and reframing public perceptions, but also necessitates tools, systems, and support that make it easier for individuals living with HIV to remain on track with their medication without judgement, fear, or unnecessary burden. AdhereTech’s smart devices can play a transformative role in achieving such goals.

- Enable Private, Personalized Support

- Many individuals living with HIV have reported nonadherence due to their fear of the stigma associated with taking their medications publicly.24 AdhereTech’s devices are specifically designed to address the physical barriers related to stigma and nonadherence. These devices provide discreet, personalized support, allowing patients to choose a dosing regimen that aligns with their daily schedule, enabling them to take their medications during times of privacy as opposed to when they are in a public setting. Moreover, patients can customize how they receive reminders: they can choose silent visual cues, a soft chime, and/or text-messaging prompts depending on their personal preferences and environment. This flexibility ensures reminders are subtle and non-disruptive for patients, helping them to remain adherent without drawing unnecessary attention to themselves.

- In addition, the bottles have no identifying labels or logos related to the type of medication inside, preserving patient privacy and reducing the risk of unwanted disclosure. Together, these features empower individuals living with HIV to manage their health with greater confidence, autonomy, and dignity, free from the fear of potential judgement.

- Empowering Patients with Support

- For many individuals living with HIV, stigma contributes to their risk of social isolation, which can further diminish medication adherence, and subsequently, translate to worsened health outcomes.25 AdhereTech utilizes the principles of behavioral psychology, creating a judgement free environment that offers the support necessary to remain adherent. Rooted in positive reinforcement, when patients take their doses consistently, they receive text-based notifications congratulating them on their adherence “streak” to encourage continued adherence. Similarly, when patients miss a dose, they receive a singular notification offering them the chance to explain why they did not take their medication, offering patients to select judgement-free, pre-written responses. Patients are never reprimanded for nonadherence, but rather provided with additional support if nonadherence persists for an extended period of time, ensuring their health and well-being remains a consistent priority.

- Additionally, AdhereTech’s care team is available 7-days a week to answer any questions regarding a patient’s device, update any patient-requested modifications (ex: changing reminder features, updating dosing windows, etc.), and connect patients with additional support upon request. This approach ensures patients feel supported in remaining adherent, but seeks to eliminate messaging fatigue by never bombarding patients with text-based messages.

- Technology: Bridging the Gap Between Clinics and Real Life

- Unfortunately, research highlights that HIV stigma is common in healthcare. Both anticipated and experienced stigma among people living with HIV can increase internalized stigma, reducing trust in healthcare providers and engagement in HIV care, such as medication adherence.26 AdhereTech’s smart devices help bridge this gap by offering real-time, discreet support that empowers patients to remain adherent without judgement. By minimizing the need for direct, in-person check-ins and allowing patients to interact with support only when needed—such as after consistent nonadherence or upon request—this approach can reduce stigma-related anxiety pertaining to the healthcare systems. Furthermore, patients can rely on AdhereTech’s care team and reminders to provide consistent support regardless of their diagnoses, which may help with rebuilding patients’ trust in the healthcare system.

- Improving Long-Term Health Outcomes

- Research consistently points to poor treatment adherence as a critical factor in HIV progression, leading to the potential for drug resistance, treatment failure, an increased risk of transmission to others, and a weakened immune system that makes individuals more susceptible to certain infections and cancers.27, 28, 29, 30 By improving adherence, AdhereTech can help to ensure viral suppression is sustained, reducing the risk of drug resistance and allowing those living with HIV to live long, healthy lives.29 Notably, higher TFV-DP levels are indicative of greater HIV suppression, with levels above 1250 f/mol necessary to achieve HIV RNA levels below the threshold of detection.31 At the end of a 12-week randomized control trial, patients utilizing AdhereTech’s device had a median TFV-DP level of 1887 f/mol compared to patients without the devices who had an average level of 1048 f/mo), demonstrating the devices impact on adherence and treatment success.31 Given nonadherence to antiretroviral drugs has been found to be associated with hospital mortality, enhancing adherence should not be viewed as an aspirational goal, but rather a necessity.32

References

1 Hiv.gov. (2025). U.S. statistics. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/data-and-trends/statistics#:~:text=Approximately%201.2%20million%20people%20in,sex%20with%20men%20(MSM)

2 Hiv.gov. (2023). What are HIV and AIDS?. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/about-hiv-and-aids/what-are-hiv-and-aids

3 Hiv.gov. (2023). HIV and AIDS: The basics. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/fact-sheets/hiv-and-aids-basics#:~:text=HIV%20attacks%20and%20destroys%20the,and%20the%20onset%20of%20AIDS

4 Medline Plus. (n.d.). HIV: PrEP and PEP. National Library of Medicine. https://medlineplus.gov/hivprepandpep.html

5 Tran, B. X., Phan, H. T., Latkin, C. A., Nguyen, H. L. T., Hoang, C. L., Ho, C. S. H., & Ho, R. C. M. (2019). Understanding Global HIV Stigma and Discrimination: Are Contextual Factors Sufficiently Studied? (GAPRESEARCH). International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(11), 1899. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16111899

6 Centers for Disease Control.(2022). Let’s stop HIV together. HHS.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/stophivtogether/hiv-stigma/index.html#:~:text=HIV%20internalized%20stigma%20can%20lead,tested%20and%20treated%20for%20HIV.

7 Mitzel, L. D., Vanable, P. A., & Carey, M. P. (2019). HIV-Related Stigmatization and Medication Adherence: Indirect Effects of Disclosure Concerns and Depression. Stigma and health, 4(3), 282–292. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000144

8 Hiv.gov. (2025). Zero HIV stigma day.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hiv.gov/events/awareness-days/zero-hiv-stigma-day

9 Hiv.gov. (2024). A timeline of HIV and AIDS. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/history/hiv-and-aids-timeline#year-1981

10 Gilead Sciences. (n.d.). History of the HIV epidemic. Gilead HIV. https://www.gileadhiv.com/landscape/history-of-hiv/

11 Cox, D., & Barros Guinle, M. I. (2024, December 12). This drug is the “breakthrough of the year” — and it could mean the end of the HIV epidemic. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/goats-and-soda/2024/12/12/g-s1-37662/breakthrough-hiv-lenacapavir

12 UNAIDS. (2024, December 31). HIV and stigma and discrimination: Human rights fact sheet series [PDF]. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/07-hiv-human-rights-factsheet-stigma-discrmination_en.pdf

13 GLAAD. (2023). State of HIV stigma study: 2023 [Data report]. GLAAD. Retrieved June 24, 2025, from https://glaad.org/endhivstigma/2023/

14 Thomas, D. J. (2023). Study finds HIV stigma persists across U.S. South. The Atlantic Journal Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/news/health-news/report-hiv-stigma-persists-across-america-especially-in-the-south/JOXEKMELVFCRRGG73LLGJFNVLU/

15 Terrence Higgins Trust. (2022, December 1). New data exposes shocking stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV [Press release]. Terrence Higgins Trust. https://www.tht.org.uk/news/new-data-exposes-shocking-stigma-and-discrimination-against-people-living-hiv

16 Perger, T., Davtyan, M., Foster, C., Evangeli, M., Berman, C., Kacanek, D., … & Bhopal, S. (2025). Impact of HIV-related stigma on antiretroviral therapy adherence, engagement and retention in HIV care, and transition to adult HIV care in pediatric and young adult populations living with HIV: A literature review. AIDS and Behavior, 29(2), 497-516.

17 Nurfalah, F., Yona, S., & Waluyo, A. (2019). The relationship between HIV stigma and adherence to antiretroviral (ARV) drug therapy among women with HIV in Lampung, Indonesia. Enfermeria clinica, 29, 234-237.

18 Masa, R., Zimba, M., Tamta, M., Zimba, G., & Zulu, G. (2022). The Association of Perceived, Internalized, and Enacted HIV Stigma With Medication Adherence, Barriers to Adherence, and Mental Health Among Young People Living With HIV in Zambia. Stigma and health, 7(4), 443–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000404

19 Kalichman, S. C., Katner, H., Banas, E., Hill, M., & Kalichman, M. O. (2020). HIV-related stigma and non-adherence to antiretroviral medications among people living with HIV in a rural setting. Social science & medicine, 258, 113092.

20 RED. (2021). 7 common myths about HIV/AIDS (and why they’re not true). RED. https://www.red.org/reditorial/aids-information/hiv-aids-myths-and-why-theyre-not-true/?gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=22333595968&gbraid=0AAAAAD-ioYqz0s5rd0s3YjJPr6DdlBJWX&gclid=Cj0KCQjw0qTCBhCmARIsAAj8C4ZPHJLaXBcUCaMW9tlp54Zp15_SpVkrTgYyf6CpBMxFK_Q-QRXZfcYaAiYOEALw_wcB

21 Chen, Y., Chen, K., & Kalichman, S. C. (2017). Barriers to HIV Medication Adherence as a Function of Regimen Simplification. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 51(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9827-3

22 Mass General Brigham. (2024). Myths and truths about HIV and AIDS. Mass General Brigham Incorporate. https://www.massgeneralbrigham.org/en/about/newsroom/articles/myths-and-truths-about-hiv-and-aids

23 NHS. (2021, April 22). HIV and AIDS – Symptoms. NHS UK. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/hiv-and-aids/symptoms/

24 Martinez, J., Harper, G., Carleton, R. A., Hosek, S., Bojan, K., Clum, G., Ellen, J., & Adolescent Medicine Trials Network (2012). The impact of stigma on medication adherence among HIV-positive adolescent and young adult females and the moderating effects of coping and satisfaction with health care. AIDS patient care and STDs, 26(2), 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2011.0178

25 Wu, Q., Tan, J., Chen, S., Wang, J., Liao, X., & Jiang, L. (2024). Incidence and influencing factors related to social isolation among HIV/AIDS patients: Protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos one, 19(7), e0307656.

26 Schweitzer, A. M., Dišković, A., Krongauz, V., Newman, J., Tomažič, J., & Yancheva, N. (2023). Addressing HIV stigma in healthcare, community, and legislative settings in Central and Eastern Europe. AIDS research and therapy, 20(1), 87.

27 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, Office of AIDS Research. (2025, January 13). HIV treatment adherence [Fact sheet]. HIVinfo. https://hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/fact-sheets/hiv-treatment-adherence

28 ViiV Healthcare. (2025, March). Treatment adherence for people living with HIV. ViiV Healthcare. https://viivhealthcare.com/ending-hiv/stories/positive-perspectives/treatment-adherence-for-people-living-with-hiv/

29 T. Tchakoute, C., Rhee, S. Y., Hare, C. B., Shafer, R. W., & Sainani, K. (2022). Adherence to contemporary antiretroviral treatment regimens and impact on immunological and virologic outcomes in a US healthcare system. PLoS One, 17(2), e0263742.

30 Schaecher, K. L. (2013). The importance of treatment adherence in HIV. AJMC, 19(12). https://www.ajmc.com/view/a472_sep13_schaecher_s231

31 Ellsworth, G. B., Burke, L. A., Wells, M. T., Mishra, S., Caffrey, M., Liddle, D., Madhava, M., O’Neal, C., Anderson, P. L., Bushman, L., Ellison, L., Stein, J., & Gulick, R. M. (2021). Randomized Pilot Study of an Advanced Smart-Pill Bottle as an Adherence Intervention in Patients With HIV on Antiretroviral Treatment. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999), 86(1), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002519

32 Neto, N. B., Marin, L. G., de Souza, B. G., Moro, A. L., & Nedel, W. L. (2021). HIV treatment non-adherence is associated with ICU mortality in HIV-positive critically ill patients. Journal of the Intensive Care Society, 22(1), 47–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1751143719898977