Vaccines have transformed global health by preventing countless deaths from infectious diseases, yet despite overwhelming scientific evidence of their safety and efficacy, vaccine hesitancy persists1. From the smallpox vaccine protests of the 19th century to the digital misinformation campaigns of the 21st, public skepticism about immunization has deep historical roots2. One of the most influential turning points in modern vaccine hesitancy was the 1998 publication of a (now-debunked) study linking vaccines to autism—a moment that continues to shape public attitudes and medication adherence.

What Is Vaccine Hesitancy?

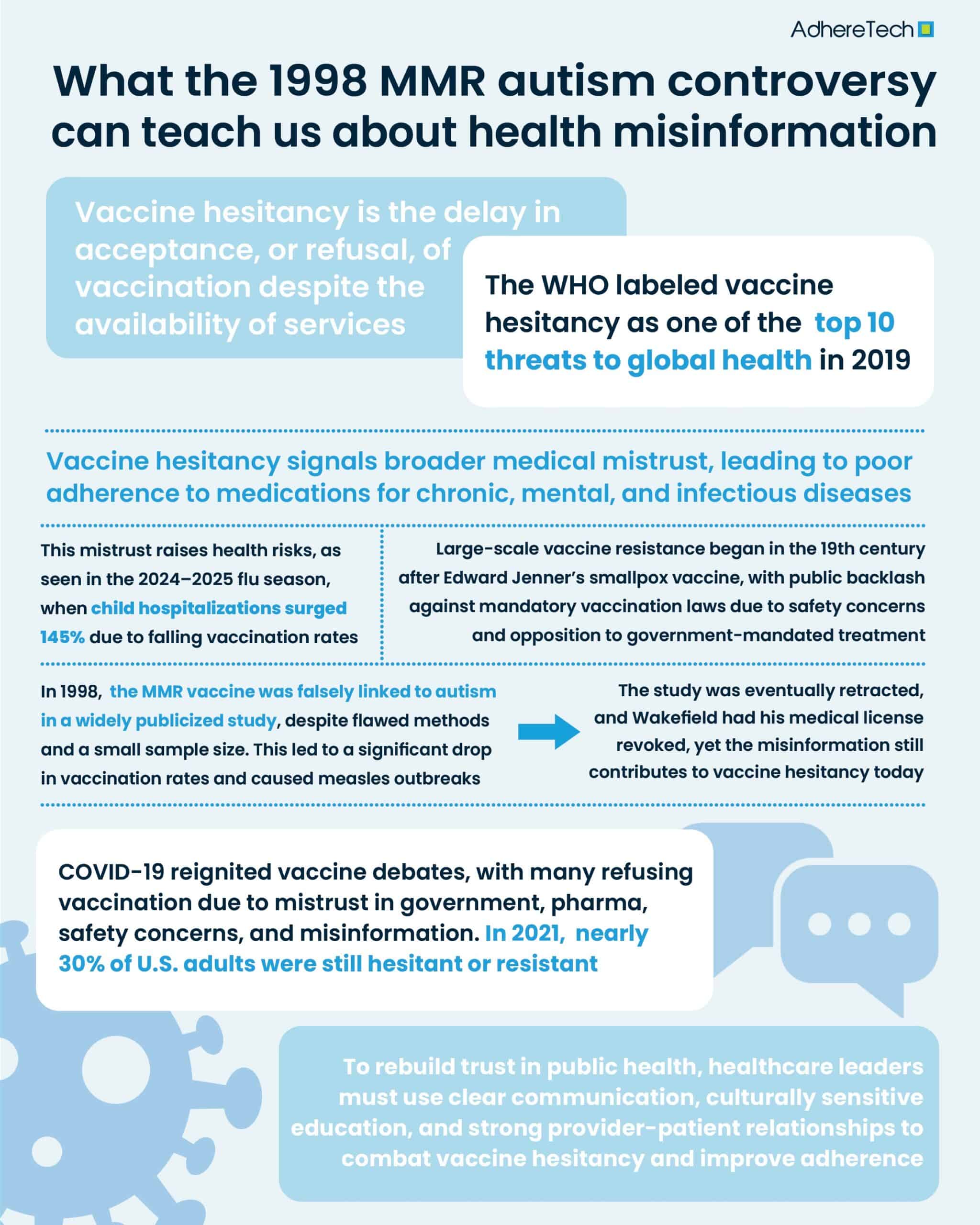

Vaccine hesitancy is the delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite the availability of services2. It’s not a new phenomenon; doubts about vaccines have existed since the earliest immunization campaigns. The World Health Organization (WHO) labeled vaccine hesitancy as one of the top 10 threats to global health in 20193.

The History of Vaccine Hesitancy: From Smallpox to the 1998 MMR Autism Study

The first recorded large-scale resistance to vaccines emerged in the 19th century, following Edward Jenner’s smallpox vaccine4. Governments in Europe and North America began enforcing mandatory vaccination laws, which triggered fierce public backlash4. Many objected to the idea of government-compelled medical treatment, while others feared the safety of a new and poorly understood medical intervention4.

Perhaps no moment in recent history has had a greater impact on vaccine hesitancy than the 1998 publication by Dr. Andrew Wakefield in The Lancet, which claimed a link between the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine and the development of autism spectrum disorders5. Despite being based on a small sample size of 12 children and having no control group, the study received widespread media attention and triggered a sharp decline in MMR vaccination rates in the UK and beyond, with MMR vaccine uptake in the UK falling from 92% in 1996 to 79% by 20036. This decline contributed to several measles outbreaks in Europe and the United States, reversing years of progress toward measles elimination.

Subsequent investigations revealed ethical violations and conflicts of interest in Wakefield’s research. In 2010, The Lancet officially retracted the study, and Wakefield lost his medical license7. Nonetheless, the damage among the public was already done.

How Vaccine Hesitancy Affects Medication Adherence

While vaccine hesitancy is specific to immunizations, it reflects broader issues of medical mistrust, which extend to medication adherence in general. Individuals who are skeptical of vaccines are also less likely to adhere to prescribed antibiotics, chronic disease medications, and mental health treatments9. A 2017 study in Vaccine found that parental vaccine hesitancy correlated with general skepticism toward pharmaceutical companies and government healthcare agencies10. This skepticism can manifest as reduced medication compliance across the board.

In clinical practice, this makes it harder for providers to ensure patients follow through on treatment plans, increasing the risk of preventable complications and hospitalizations. For instance, during the 2024–2025 flu season, pediatric flu hospitalizations surged by 145% compared to the previous year, with over 86 child deaths reported by mid-February. Experts attributed this increase, in part, to declining vaccination rates among children, which fell to 46% from 51% the previous year, largely due to vaccine hesitancy and misinformation11,12.

COVID Vaccine Hesitancy: A Contemporary Case Study in Misinformation and Public Distrust

The COVID-19 pandemic reignited the global debate around vaccines. Despite the rapid development of highly effective vaccines, significant segments of the population refused them due to distrust in government and pharmaceutical companies, concerns over safety and speed of development, and the influence of misinformation and conspiracy theories13. A 2021 Pew Research Center survey found that nearly 30% of U.S. adults remained hesitant or resistant to COVID-19 vaccines, even at the peak of pandemic-related deaths14. This resistance mirrored patterns first seen following the Wakefield study—demonstrating the long-lasting impact of past misinformation and the continued influence of social and cultural beliefs on health behaviors.

Healthcare providers, scientists, and policymakers must work to rebuild trust in public health. Strategies to combat vaccine hesitancy and improve medication adherence may include clear and transparent communication about risks and benefits, culturally sensitive education that addresses community-specific concerns, and strengthening of provider-patient relationships to foster trust.

Vaccine hesitancy is not a new phenomenon, but its modern form—amplified by misinformation and shaped by historical missteps like the 1998 Wakefield study—poses serious threats to public health. The ripple effect extends beyond immunizations, undermining medication adherence and trust in healthcare systems more broadly.

References

- Greenwood, Brian. “The Contribution of Vaccination to Global Health: Past, Present and Future.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 369, no. 1645, 19 June 2014, pp. 20130433–20130433, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4024226/, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0433.

- Browne, Matthew. “Epistemic Divides and Ontological Confusions: The Psychology of Vaccine Scepticism.” Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, vol. 14, no. 10, 22 June 2018, pp. 2540–2542, https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2018.1480244.

- World Health Organization. “Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019.” World Health Organization, 2019, www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019.

- Riedel, Stefan. “Edward Jenner and the History of Smallpox and Vaccination.” Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, vol. 18, no. 1, 2005, pp. 21–25, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1200696/, https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2005.11928028.

- Wakefield, Andrew J. “MMR Vaccination and Autism.” The Lancet, vol. 354, no. 9182, 11 Sept. 1999, pp. 949–950, www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(05)75696-8/fulltext, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(05)75696-8.

- Lever, Anna-Marie. “MMR Vaccine Uptake Reaches 14-Year High.” BBC News, 27 Nov. 2012, www.bbc.com/news/health-20510525.

- Rao, T. S. Sathyanarayana, and Chittaranjan Andrade. “The MMR Vaccine and Autism: Sensation, Refutation, Retraction, and Fraud.” Indian Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 53, no. 2, June 2011, pp. 95–96, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3136032/, https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.82529.

- BBC Trending. “The Volunteers Using “Honeypot” Groups to Fight Anti-Vax Propaganda.” BBC News, 10 May 2021, www.bbc.co.uk/news/blogs-trending-57051691.

- IOVA, CAMELIA FLORINA, et al. “Vaccine Adherence: From Vaccine Hesitancy to Actual Vaccination and Reasons for Refusal of Childhood Vaccines in a Group of Postpartum Mothers.” In Vivo, vol. 39, no. 1, 31 Dec. 2024, pp. 509–523, iv.iiarjournals.org/content/invivo/39/1/509.full.pdf, https://doi.org/10.21873/invivo.13855.

- McClure, Catherine C., et al. “Vaccine Hesitancy: Where We Are and Where We Are Going.” Clinical Therapeutics, vol. 39, no. 8, Aug. 2017, pp. 1550–1562, www.clinicaltherapeutics.com/article/S0149-2918(17)30770-1/fulltext, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.07.003.

- Malhi, Sabrina. “Rise of Pediatric Flu Cases Is Sending More Children to the Hospital.” The Washington Post, Mar. 2025, www.washingtonpost.com/health/2025/03/01/flu-season-children-hospitalized/?utm. Accessed 19 May 2025.

- Pracht, Etienne, et al. “Vaccine-Preventable Conditions: Disparities in Hospitalizations Affecting Rural Communities in the Southeast United States.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 22, no. 4, 21 Mar. 2025, pp. 466–466, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040466. Accessed 30 Mar. 2025.

- Troiano, Gianmarco, and Alessandra Nardi. “Vaccine Hesitancy in the Era of COVID-19.” Public Health, vol. 194, no. 1, Mar. 2021, pp. 245–251, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7931735/, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2021.02.025.

- Pew Research Center. (2021, March 5). Growing share of Americans say they plan to get a COVID-19 vaccine—or already have. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2021/03/05/growing-share-of-americans-say-they-plan-to-get-a-covid-19-vaccine-or-already-have/