How The Birth Control Pill Changed Society

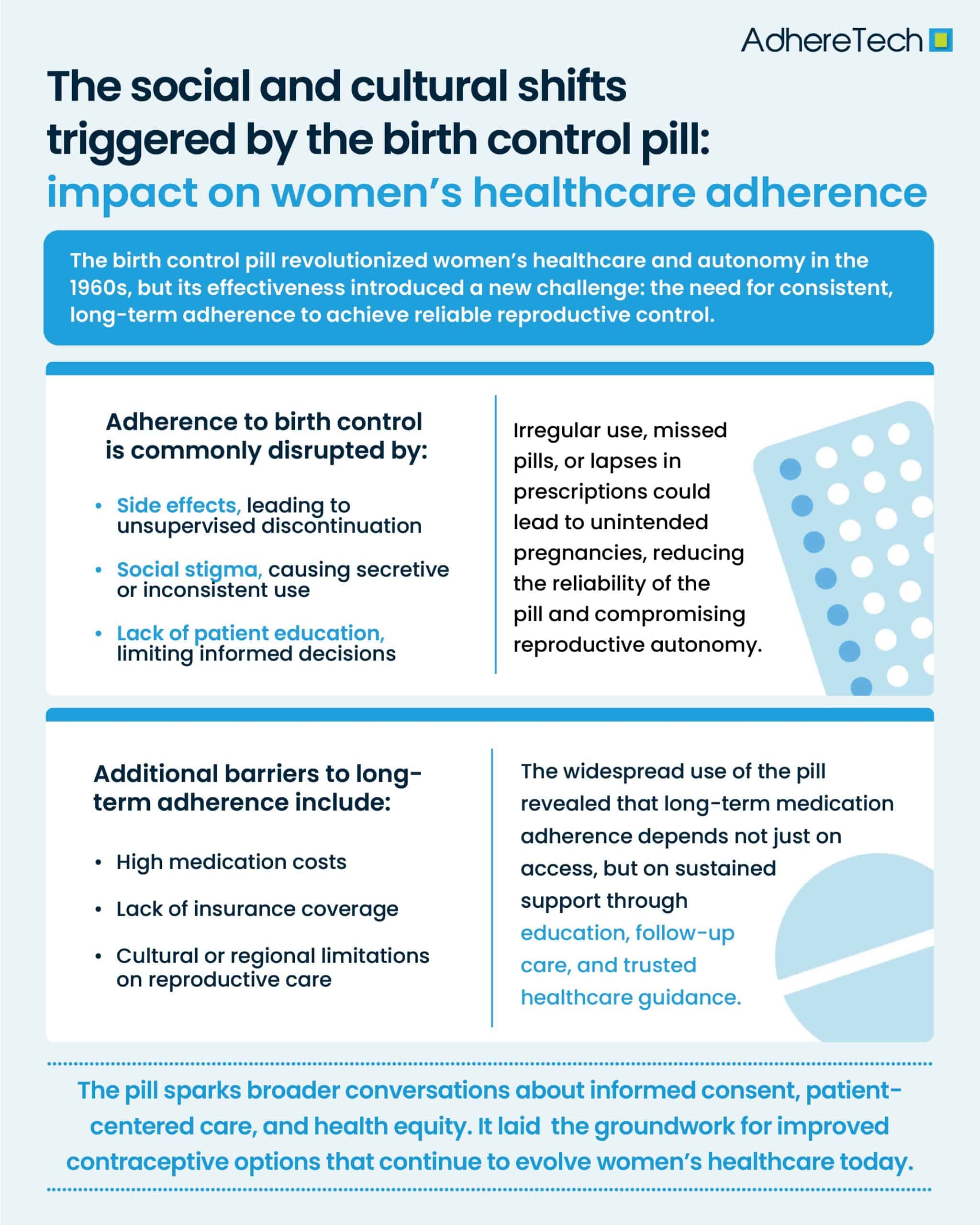

The introduction of the birth control pill in the 1960s marked a revolutionary shift in both social dynamics and women’s healthcare1. The pill offered a convenient, private, and highly effective means of contraception, offering unprecedented control over reproduction1. The pill became a symbol of women’s liberation, enabling greater autonomy in family planning and shifting the societal expectations around women’s roles2. However, alongside the pill’s benefits came a new challenge: adherence. Unlike traditional fertility control methods, such as condoms, diaphragms, and sterilization, the pill required consistent, daily use to work as intended3. This marked a significant shift in women’s healthcare routines, highlighting the need for long-term medication aThe Double-Edged Sword of Easy Access and Daily Responsibility”dherence to achieve desired health outcomes.

The Double-Edged Sword of Easy Access and Daily Responsibility

While the pill itself was highly effective when taken as directed, missed doses, inconsistent timing, or interruptions in access to prescriptions could all lead to unintended pregnancies, undermining the autonomy the pill was intended to provide2. Furthermore, the near immediate availability of the pill led to a lack of consideration and discussion regarding its consequences, such as adverse side effects – which led some women to discontinue the pill without medical guidance3. This ease of access to the pill led to a lack of attention to routine health monitoring, such as regular gynecological exams, blood pressure checks, and awareness of potentially harmful side effects4.

Cultural Stigma and Systemic Barriers to Adherence

Although early public health efforts around the pill highlighted the importance of regular use, structural and cultural barriers continued to remain. In many regions, this social stigma regarding the pill persisted for decades, influencing how women viewed their own use of contraception and adherence to long-term medication5.

Social Judgment and Secrecy Around Contraceptive Use

Some faced societal disapproval or judgment, leading to secrecy or inconsistent usage4. Additionally, healthcare disparities meant many women faced challenges due to high costs, lack of insurance, or cultural restrictions, impacting their ability to adhere to preventive health measures, including the pill6. The pill’s widespread use showed the medical community that women wanted greater control over their healthcare decisions and that they expected providers to respect their agency7. This shift led to more dialogue about informed consent, patient education, and a growing recognition of the importance of patient-centered care. This laid the foundation for modern discussions regarding adherence to long-term medications for chronic diseases and preventative care7.

The Ongoing Evolution of Reproductive Healthcare

The birth control pill was revolutionary in its time, but it also marked the beginning of an ongoing conversation about women’s health and autonomy. As the cultural and medical landscapes continue to evolve, so too will women’s healthcare. In recent years, new forms of contraception, such as intrauterine devices (IUDs), implants, and emergency contraception, have further expanded choices for women, giving them more options for managing their reproductive health8. Technology, too, is transforming healthcare adherence for women, with apps and digital tools helping women track their medication schedules and access reproductive healthcare more efficiently9.

A Lasting Legacy of Freedom and Responsibility

The birth control pill wasn’t just a medical breakthrough—it was a social revolution that reshaped women’s healthcare. It gave women control over their reproductive futures and paved the way for a more inclusive conversation about women’s healthcare needs. However, with this new freedom came new responsibilities, including the need to enhance long-term adherence, offering ongoing education and support to empower women to make their own informed, supported decisions regarding their health.

References

- Tyrer, Louise. “Introduction of the Pill and Its Impact.” Contraception, vol. 59, no. 1, Jan. 1999, pp. 11S16S, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10342090/, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010-7824(98)00131-0.

- Mayo Clinic Staff. “Combination Birth Control Pills – Mayo Clinic.” Mayoclinic.org, 13 Jan. 2023, www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/combination-birth-control-pills/about/pac-20385282.

- National Museum of Australia. “The Pill | National Museum of Australia.” Nma.gov.au, 2014, www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/the-pill, https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/the-pill.

- National Research Council (US) Committee on Population. “Contraceptive Benefits and Risks.” Nih.gov, National Academies Press (US), 2011, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK235069/.

- Britton, Laura E., et al. “An Evidence-Based Update on Contraception.” AJN, American Journal of Nursing, vol. 120, no. 2, Feb. 2020, pp. 22–33, journals.lww.com/ajnonline/Fulltext/2020/02000/CE__An_Evidence_Based_Update_on_Contraception.23.aspx?context=FeaturedArticles&collectionId=1, https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000654304.29632.a7.

- Daher, Marilyne, et al. “Gender Disparities in Difficulty Accessing Healthcare and Cost-Related Medication Non-Adherence: The CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Survey.” Preventive Medicine, vol. 153, Dec. 2021, p. 106779, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106779.

- Dehlendorf Christine,, et al. “Contraceptive Counseling.” Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, vol. 57, no. 4, Dec. 2014, pp. 659–673, https://doi.org/10.1097/grf.0000000000000059.

- Better Health Channel. “Contraception – Choices.” Vic.gov.au, 18 Oct. 2022, www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/healthyliving/contraception-choices.

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION. “Digital Tools Can Help Improve Women’s Health and Promote Gender Equality, WHO Report Shows.” Www.who.int, 8 Mar. 2024, www.who.int/europe/news/item/08-03-2024-digital-tools-can-help-improve-women-s-health-and-promote-gender-equality–who-report-shows.