Health insurance plays a pivotal role in facilitating access to medications and ensuring adherence to prescribed treatment regimens, especially in the USA, where medical fees can be extremely high. While insurance coverage can alleviate financial burdens and improve health outcomes, its effectiveness is influenced by various factors, including the structure of the insurance plan, out-of-pocket costs, and the presence of additional government healthcare support services. Furthermore, in 2023, approximately 9.5% of Americans were uninsured– which translates to roughly 25.3 million people1.

Impact of Health Insurance on Medication Access

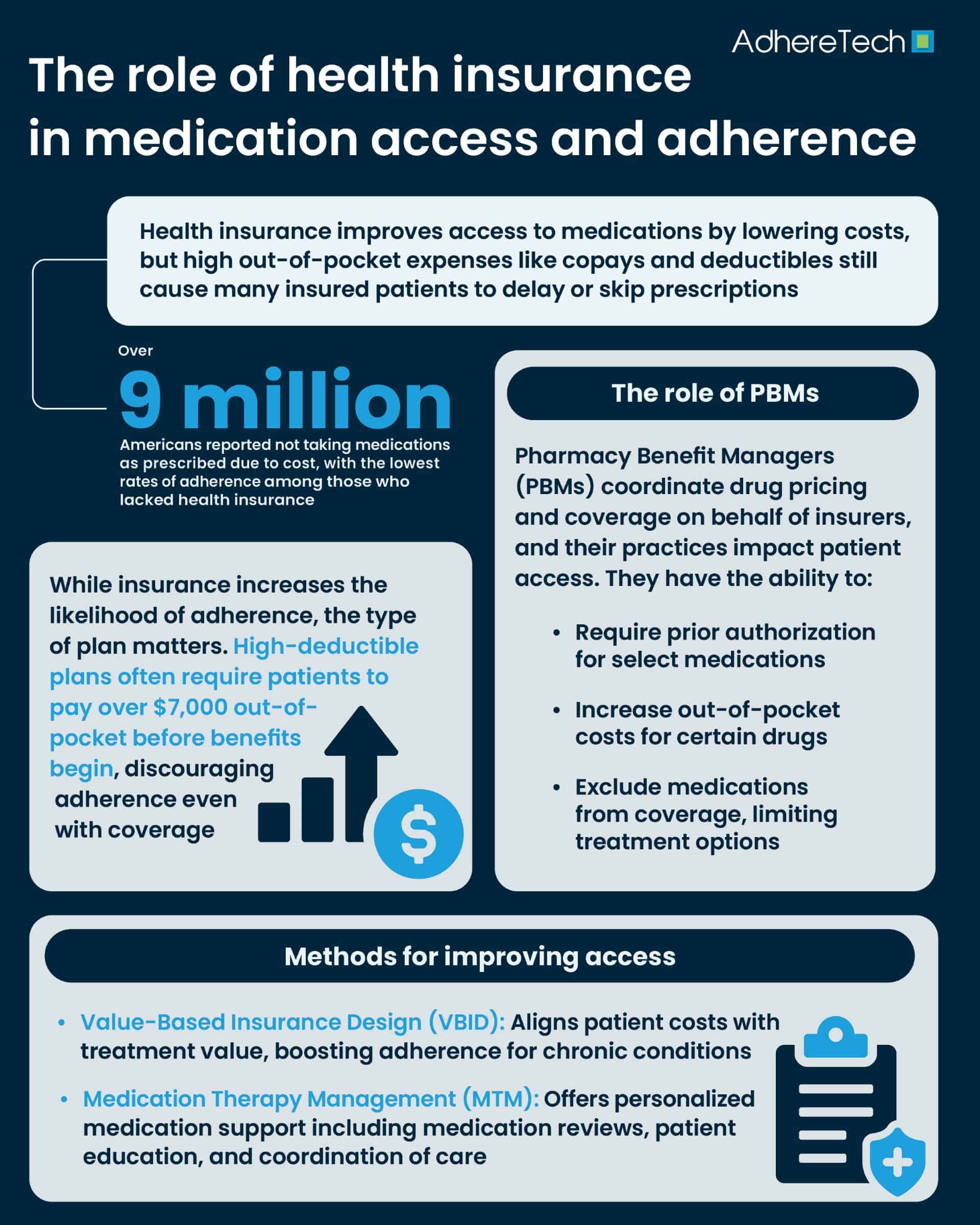

Health insurance coverage can significantly enhance access to necessary medications. Individuals with insurance are more likely to fill prescriptions promptly, reducing the risk of disease progression and complications. For instance, a study published in Preventing Chronic Disease found that a substantial portion of individuals aged 35 to 64 with employer-sponsored health insurance were more likely to adhere to antihypertensive medications compared to those without insurance coverage (41%)2 .

However, the type of insurance plan matters. High-deductible health plans (HDHPs), while lower in monthly premiums, often result in higher out-of-pocket costs for medications. Under HDHPs, patients are required to cover all the costs relating to non-preventative medications until they meet their deductible; in 2021, annual out-of-pocket deductibles were estimated at a minimum of $7,000 before insurance benefits kick in3. Resultantly, for non-preventative medications, patients must spend upwards of $7,000 in medication and healthcare costs before their insurance kicks in and they begin reaping the financial benefits of their plans. Even for preventative medications, only some HDHPs provide coverage before the deductible has been reached.

Moreover, while other insurance plans exist, a series of limitations such as high premiums, the need for referrals, and limitations to in-network providers can all create additional financial burdens that can deter patients from filling prescriptions or lead to partial adherence, undermining the intended benefits of insurance coverage. Research indicates that even modest increases in out-of-pocket expenses can significantly impact medication adherence4.

Financial Barriers Despite Insurance Coverage

Despite having health insurance, many individuals face financial barriers that impede medication access. High co-payments, deductibles, and co-insurance costs can accumulate, resulting in patients unable to afford their medications, especially for those with chronic conditions requiring long-term treatment. A report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revealed that over 9 million American adults did not take their medications as prescribed due to cost, with the lowest rates of adherence among those who lacked health insurance, but still impacting those with insurance coverage as well, emphasizing the limitations of certain insurance coverage5.

These financial constraints can lead patients to skip doses, reduce medication intake, or delay refills, strategies that can exacerbate health conditions and increase long-term healthcare costs. Addressing these financial barriers is crucial to improving medication adherence and overall health outcomes.

Role of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs)

Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) are intermediaries between insurers, pharmacies, and drug manufacturers6. They negotiate drug prices, manage formularies, and process prescription claims. While PBMs aim to reduce costs, their practices can sometimes create obstacles to medication access. For example, the requirement for prior authorization can delay the initiation of necessary treatments, particularly for medications used in opioid addiction therapy.

Additionally, PBMs may influence medication choices through formulary decisions, potentially limiting access to certain drugs. While these measures can reduce costs, they may also restrict patient access to the most “appropriate” medications for their conditions. For instance, PBMs can establish tier placements, with brand-name drugs often placed in higher tiers requiring higher out-of-pocket fees, and potentially limiting access7, which is particularly important for patients where generic medications are not available.

Value-Based Insurance Design

Value-Based Insurance Design (VBID) is an approach that aligns patients’ out-of-pocket costs with the value of services8. By reducing or eliminating copayments for high-value medications, VBID aims to encourage adherence to treatments that offer significant health benefits. Implementations of VBID have shown improvements in medication adherence for chronic conditions such as asthma, hypertension, and diabetes8.

This approach not only enhances medication adherence but also promotes better health outcomes by ensuring that patients have access to necessary treatments without financial deterrents.

Medication Therapy Management (MTM) Services

Medication Therapy Management (MTM) services are designed to optimize therapeutic outcomes for patients9. These services include medication reviews, patient education, and coordination of care. In the United States, Medicare Part D plans are required to offer MTM services to eligible beneficiaries, aiming to improve medication adherence and reduce adverse drug events10.

MTM services have been associated with improved medication adherence, particularly among patients with multiple chronic conditions11. A systematic review published in the Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy examined the impact of MTM services on medication adherence across various chronic diseases, and found that MTM interventions led to statistically significant improvements in medication adherence, as measured by the proportion of days covered across these conditions12. By providing personalized support, MTM services help patients manage their medications effectively, leading to better health outcomes.

Global Perspectives on Health Insurance and Medication Adherence

The impact of health insurance on medication adherence varies globally, influenced by the structure and accessibility of healthcare systems. In countries with universal health coverage, such as the United Kingdom, medication adherence rates tend to be higher due to reduced financial barriers13. Conversely, in nations without universal healthcare systems in place, individuals may face significant challenges in accessing medications, leading to lower adherence rates14.

In sub-Saharan Africa, countries like Ghana and Nigeria have implemented national health insurance schemes to improve medication access15. A study assessing the impact of these schemes found that enrollment in health insurance was associated with better medication adherence and blood pressure control among hypertensive patients. Specifically, patients enrolled in the National Health Insurance Authority had an adjusted odds ratio of a 4.5 improvement in medication adherence and 2.6 for improvements in blood pressure control16. However, even when the financial burdens associated with medication adherence are minimized, additional challenges remain, including low enrollment rates and disparities in accessing healthcare services.

Health insurance is a critical factor in medication access and adherence. While it can reduce financial barriers and improve health outcomes, its effectiveness is contingent upon the design of the insurance plan, the affordability of medications, and the availability of supportive services. Policymakers and healthcare providers must collaborate to address these factors, ensuring that health insurance fulfills its potential in promoting medication adherence and enhancing public health.

References

- Tolbert, Jennifer, et al. “Key Facts about the Uninsured Population.” Kaiser Family Foundation, 18 Dec. 2024, www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/.

- Baker-Goering, Madeleine M., et al. “Relationship between Adherence to Antihypertensive Medication Regimen and Out-of-Pocket Costs among People Aged 35 to 64 with Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance.” Preventing Chronic Disease, vol. 16, 21 Mar. 2019, https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd16.180381. Accessed 17 May 2020.

- “Frequently Asked Questions.” U.S. Office of Personnel Management, 2019, www.opm.gov/healthcare-insurance/healthcare/health-savings-accounts/frequently-asked-questions/.

- Hatah, Ernieda, et al. “How Payment Scheme Affects Patients’ Adherence to Medications? A Systematic Review.” Patient Preference and Adherence, May 2016, p. 837, https://doi.org/10.2147/ppa.s103057.

- Mykyta, Laryssa, and Robin Cohen. “Characteristics of Adults Aged 18–64 Who Did Not Take Medication as Prescribed to Reduce Costs: United States, 2021.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2 June 2023, stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/127680.

- Bollmeier, Suzanne G, and Scott Griggs. “The Role of Pharmacy Benefit Managers and Skyrocketing Cost of Medications.” Missouri Medicine, vol. 121, no. 5, Sept. 2024, p. 403, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11482839/.

- “Comer Releases Report on PBMs’ Harmful Pricing Tactics and Role in Rising Health Care Costs – United States House Committee on Oversight and Accountability.” United States House Committee on Oversight and Accountability, 25 July 2024, oversight.house.gov/release/comer-releases-report-on-pbms-harmful-pricing-tactics-and-role-in-rising-health-care-costs%ef%bf%bc/.

- Lee, Joy L., et al. “Value-Based Insurance Design: Quality Improvement but No Cost Savings.” Health Affairs, vol. 32, no. 7, July 2013, pp. 1251–1257, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0902. Accessed 9 Nov. 2021.

- Farley, Joel F. “Are the Benefits of Value-Based Insurance Design Conclusive?” Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, vol. 25, no. 7, 22 June 2019, pp. 736–738, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10397703/, https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2019.25.7.736. Accessed 17 June 2025.

- Yasin, Nanang Munif, et al. “Bridging Gaps in Medication Therapy Management at Community Health Centers: A Mixed-Methods Study on Patient Perceptions and Pharmacists’ Preparedness.” Exploratory Research in Clinical and Social Pharmacy, vol. 17, 16 Dec. 2024, p. 100554, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2667276624001513, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcsop.2024.100554.

- “American College of Clinical Pharmacy ® | ACCP.” Www.accp.com, www.accp.com/docs/govt/advocacy/Leadership%20for%20Medication%20Management%20-%20MTM%20101.pdf.

- de Oliveira, Djenane Ramalho, et al. “Medication Therapy Management: 10 Years of Experience in a Large Integrated Health Care System.” Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, vol. 26, no. 9, Sept. 2020, pp. 1057–1066, https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2020.26.9.1057.

- House, Elizabeth. “Elizabeth House Hospital.” Elizabeth House Hospital, 2025, www.elizabethhousehospital.co.uk/treatment-and-therapies/medication-therapy-management-mtm. Accessed 17 June 2025.

- Schönfeld, Sandra, et al. “Prevalence and Correlates of Cost-Related Medication Nonadherence to Immunosuppressive Drugs after Heart Transplantation.” Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, vol. Publish Ahead of Print, 18 May 2020, https://doi.org/10.1097/jcn.0000000000000683. Accessed 7 Aug. 2020.

- World Health Organization. “Universal Health Coverage (UHC).” World Health Organization, 26 Mar. 2025, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc).

- Carapinha, João L., et al. “Health Insurance Systems in Five Sub-Saharan African Countries: Medicine Benefits and Data for Decision Making.” Health Policy, vol. 99, no. 3, Mar. 2011, pp. 193–202, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.11.009.