Medication adherence is a critical component of effective healthcare, particularly for patients managing chronic diseases. Despite its importance, non-adherence remains a persistent challenge globally, with estimates suggesting that up to 50% of patients with chronic illnesses do not follow their prescribed treatment regimens1. In response, healthcare providers, insurers, and policymakers have increasingly explored compliance-based incentives—rewards or penalties linked to adherence—to improve health outcomes. However, the ethical implications of such strategies raise a series of complex questions and concerns.

Understanding Compliance-Based Incentives

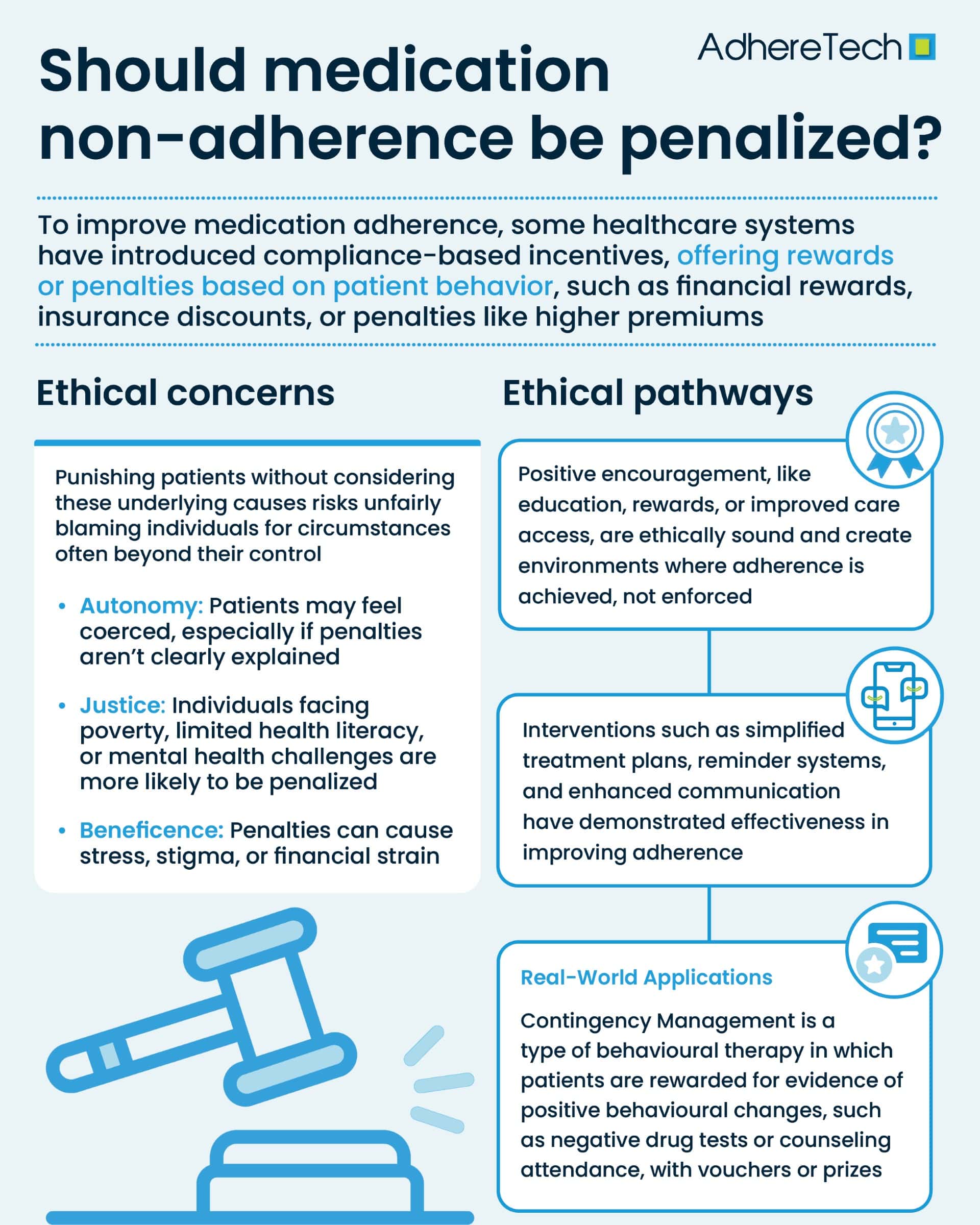

Compliance-based incentives are mechanisms designed to encourage patients to follow medical advice, including medication adherence, lifestyle modifications, or attendance at follow-up appointments2. These incentives can take many forms, including financial rewards, reduced insurance premiums, or conversely, penalties such as increased costs or denial of benefits for non-compliance2.

Research has found that incentivizing adherence can improve health outcomes, reduce healthcare costs, and foster a more efficient healthcare system. For example, a 2015 study in Health Affairs found that modest financial incentives improved medication adherence among patients with chronic conditions (the incentive group had significantly higher rates of smoking cessation than the information-only group, at 9–12 months after enrollment (14.7% vs. 5.0%) and 15–18 months after enrollment (9.4% vs. 3.6%)3. Yet, the approach is not without controversy, as questions remain about the fairness and potential unintended consequences of rewarding or punishing patient behavior.

Ethical Concerns Around Penalizing Non-Adherence

Penalizing non-adherence is a contentious ethical issue because it touches upon the principles of autonomy, justice, and beneficence4. Non-adherence can result from various factors, including socioeconomic barriers, mental health issues, lack of understanding, or side effects of medications5. Punishing patients without considering these underlying causes risks unfairly blaming individuals for circumstances often beyond their control.

At the core of medical ethics lies respect for patient autonomy—the right of individuals to make informed decisions about their own health6. Penalizing non-adherence may infringe upon this autonomy, especially if patients are not fully informed about the rationale for penalties or do not have meaningful alternatives. The threat of penalties could coerce patients into compliance without genuine understanding or agreement, which undermines trust in the patient-provider relationship.

Healthcare justice demands that policies do not disproportionately disadvantage vulnerable populations7. Non-adherence is often higher among patients facing socioeconomic hardships, limited health literacy, or systemic barriers to care8. Penalizing non-adherence without addressing these root causes risks exacerbating health inequities, as disadvantaged patients may be unable to comply despite their best efforts. Thus, punitive measures may unfairly burden those already marginalized.

The principles of beneficence (promoting well-being) and non-maleficence (avoiding harm) require that interventions improve patient health without causing undue harm9. While incentivizing adherence can enhance outcomes, penalties might induce stress, stigma, or financial hardship, potentially worsening health or leading patients to disengage from care entirely10.

The Role of Incentives Versus Penalties

Ethical healthcare interventions tend to favor incentives over penalties11. Positive incentives—such as rewards, educational support, or enhanced access to care—align better with respect for autonomy and justice11. These strategies empower patients and recognize the challenges they face in adhering to treatment.

Financial rewards, for example, have been shown to improve adherence in various contexts, including smoking cessation and diabetes management3. However, the sustainability of such incentives remains a concern, as benefits often diminish once incentives are removed.

On the other hand, penalties risk alienating patients and damaging trust12. In some health insurance models, increasing premiums or denying coverage for non-adherence have been proposed but rarely implemented due to ethical and legal concerns12. Moreover, penalties could lead patients to conceal non-adherence or avoid healthcare to escape repercussions.

Addressing Barriers to Adherence

Before considering penalties, it is critical to address systemic and personal barriers to adherence. These may include financial constraints, complex medication regimens, forgetfulness, side effects, or psychological factors5. Interventions such as patient education, simplified treatment plans, reminder systems, and enhanced communication with healthcare providers have demonstrated effectiveness in improving adherence13.

Efficacy of Incentive Programs For Treatment Adherence

Contingency management (CM) in substance use disorder treatment offers a useful lens through which to examine compliance incentives ethically14. CM provides patients with immediate rewards—often vouchers or prizes—when they demonstrate desired behaviors such as negative drug tests or attendance at counseling sessions14.

Research consistently shows CM’s effectiveness in promoting abstinence and engagement in treatment programs15. Importantly, CM operates through positive reinforcement rather than punishment, respecting patient autonomy by encouraging voluntary behavior change14. Patients are motivated by rewards rather than coerced by penalties, fostering a collaborative rather than adversarial relationship.

Furthermore, CM programs often incorporate individualized support to address barriers, such as transportation assistance or counseling, which mitigates justice concerns14. By recognizing and addressing social determinants, CM aligns more closely with ethical principles.

Balancing Public Health and Individual Rights

The debate over penalizing non-adherence also involves balancing public health interests with individual rights. Non-adherence can increase healthcare costs and contribute to poorer population health5. In some cases, such as infectious diseases, non-adherence may pose serious risks to others, justifying stronger measures.

Nevertheless, coercive penalties may backfire by increasing distrust and disengagement. Ethical frameworks suggest that public health policies should prioritize education, support, and voluntary participation, reserving penalties only for extreme or willful non-compliance that endangers others16.

Ethical Pathways Forward

The ethics of compliance-based incentives demand careful consideration of patient autonomy, justice, and beneficence. While improving medication adherence is a worthy goal, penalizing non-adherence often risks harming vulnerable patients and undermining trust in healthcare systems. Instead, ethically sound strategies focus on positive incentives, addressing barriers to adherence, and engaging patients through supportive, empowering interventions.

Healthcare policymakers and providers should strive to create environments where adherence is achievable and rewarding, not coerced or punished.

References

- Brown, Marie T., and Jennifer K. Bussell. “Medication Adherence: WHO Cares?” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, vol. 86, no. 4, Apr. 2011, pp. 304–314, https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0575.

- Aremu, Taiwo Opeyemi, et al. “Medication Adherence and Compliance: Recipe for Improving Patient Outcomes.” Pharmacy, vol. 10, no. 5, 2022, pp. 1–5, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9498383/, https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10050106.

- Volpp, K.G., et al. “A Randomized Controlled Trial of Financial Incentives for Smoking Cessation.” Journal of Vascular Surgery, vol. 49, no. 5, May 2009, pp. 1358–1359, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2009.03.023. Accessed 26 Oct. 2019.

- Varkey, Basil. “Principles of Clinical Ethics and Their Application to Practice.” Medical Principles and Practice, vol. 30, no. 1, 4 June 2020, pp. 17–28, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7923912/, https://doi.org/10.1159/000509119.

- Aljofan, Mohamad, et al. “The Rate of Medication Nonadherence and Influencing Factors: A Systematic Review.” Electronic Journal of General Medicine, vol. 20, no. 3, 1 May 2023, p. em471, https://doi.org/10.29333/ejgm/12946.

- Nineham, Laura. “Medical Ethics: Autonomy.” The Medic Portal, Dukes Education, 2020, www.themedicportal.com/application-guide/medical-school-interview/medical-ethics/medical-ethics-autonomy/.

- NHS England. “NHS England» a National Framework for NHS – Action on Inclusion Health.” Www.england.nhs.uk, 2023, www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/a-national-framework-for-nhs-action-on-inclusion-health/.

- “Suplemento Do XV Congresso de Trauma E Emergência Da Zona Da Mata Mineira.” Revista Médica de Minas Gerais, vol. 33, no. Supl.9, 1 Jan. 2023, https://doi.org/10.5935/2238-3182.v33s9. Accessed 31 May 2024.

- Tulane University. “Ethics in Health Care: Improving Patient Outcomes.” Tulane University, 19 Jan. 2023, publichealth.tulane.edu/blog/ethics-in-healthcare/.

- Krist, Alex H, et al. “Engaging Patients in Decision-Making and Behavior Change to Promote Prevention.” Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, vol. 240, no. 28972524, 2020, p. 284.

- Vlaev, Ivo, et al. “Changing Health Behaviors Using Financial Incentives: A Review from Behavioral Economics.” BMC Public Health, vol. 19, no. 1, 7 Aug. 2019, p. 1059, bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-019-7407-8, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7407-8.

- Smith, Carly. “First, Do No Harm: Institutional Betrayal and Trust in Health Care Organizations.” Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, vol. Volume 10, no. 10, Apr. 2017, pp. 133–144, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5388348/, https://doi.org/10.2147/jmdh.s125885.

- Schnorrerova, Patricia, et al. “Medication Adherence and Intervention Strategies: Why Should We Care.” Bratislava Medical Journal, 10 June 2025, https://doi.org/10.1007/s44411-025-00227-0. Accessed 14 June 2025.

- McPherson, Sterling, et al. “A Review of Contingency Management for the Treatment of Substance-Use Disorders: Adaptation for Underserved Populations, Use of Experimental Technologies, and Personalized Optimization Strategies.” Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, vol. Volume 9, Aug. 2018, pp. 43–57, https://doi.org/10.2147/sar.s138439.

- Prendergast, Michael, et al. “Contingency Management for Treatment of Substance Use Disorders: A Meta-Analysis.” Addiction, vol. 101, no. 11, Nov. 2006, pp. 1546–1560, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x.

- Turoldo, Fabrizio. “Responsibility as an Ethical Framework for Public Health Interventions.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 99, no. 7, July 2009, pp. 1197–1202, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2696664/, https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2007.127514.