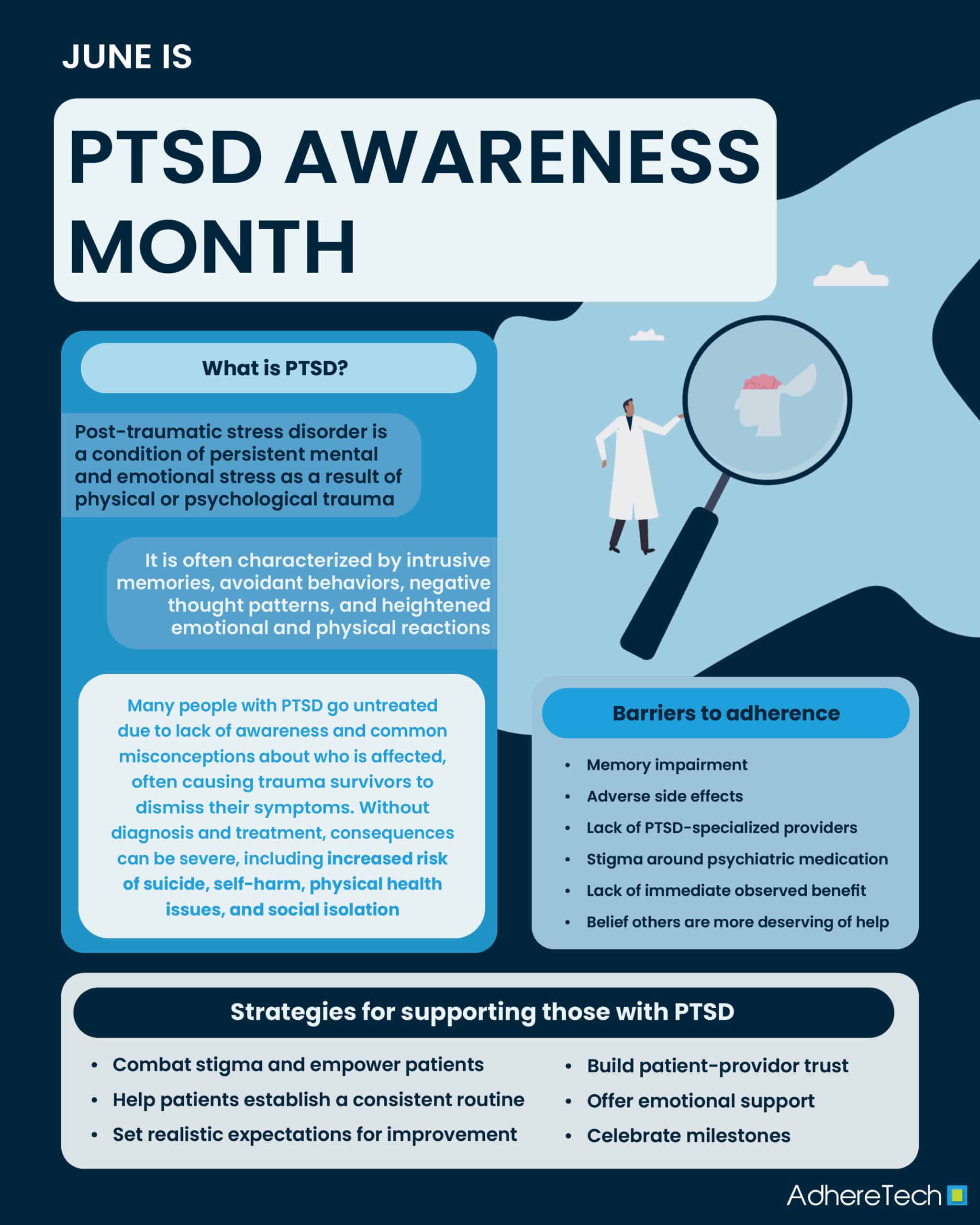

Post-traumatic stress disorder, commonly referred to as PTSD, is defined as persistent mental and emotional stress as a result of physical or psychological trauma, often characterized by intrusive memories of the traumatic event, avoidance of the event both physically and mentally, negative changes in thoughts and mood as well as physical and emotional reactions.1 Although 70% of people will experience a potentially traumatic event at some point in their lives, only 5.6% go on to develop PTSD.2 While the reasons for this are still largely unknown, particular risk factors–such as mental health issues, a lack of social support, prolonged or early exposure to a traumatic event/experience, and physical injury from a traumatic event–can increase the likelihood of an individual developing PTSD.1

An estimated 40% of people with PTSD recover within one year, with treatments often entailing psychotherapy and/or medications, such as anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medicines.2 However, numerous barriers prevent patients from seeking treatment, resulting in only 50% of people with PTSD seeking treatment, and of those, only 58% receiving care from a mental health professional.3 Unfortunately, many patients who meet the criteria for a PTSD diagnosis do not receive appropriate treatment, often due to a lack of understanding or awareness.4 For instance, PTSD is frequently—but inaccurately—associated solely with military combat, leading to misconceptions about who can be affected.5 The myth that veterans are the only individuals who develop PTSD, in addition to the majority of people considering veterans as exclusively men, can cause the facts to be overlooked.5, 6 For instance, women veterans experience disproportionately high rates of PTSD compared to male veterans (13% vs. 6%).7 Moreover, the lifetime prevalence of PTSD is about two to three times higher in women (10-12%) compared to men (5-6%), with women more exposed to high-impact trauma than men, such as sexual trauma.8 The stigma and misconceptions surrounding PTSD can prevent those having experienced non-combat forms of trauma (such as natural disasters, sexual trauma, personal violence, etc.) from seeking help.9

Likewise, many primary care providers lack clinician awareness of PTSD symptoms, and may fail to ask their patients about traumatic experiences, focusing instead on the depressive or anxiety symptoms that often accompany PTSD, leading to the condition being overlooked.10, 11 Without the appropriate diagnosis, proper treatment cannot ensue, and the consequences are immense, including an increased risk of suicide, self-harm, physical health conditions, and social isolation.12

Unfortunately, even for patients who receive the appropriate diagnosis and treatment plan for PTSD, challenges in remaining adherent to the designated treatment plan persist. For instance, the Mind Your Heart Study found that PTSD was associated with significantly lower levels of medication adherence, even after controlling for depression, demographics, alcohol use, and medical comorbidities (Adjusted OR = 1.47, 95% CI 1.03-2.10; P = 0.04).13 Notably, patients with PTSD were more likely to report forgetting (Unadjusted OR 1.90, 95% CI 1.44-2.52, P < 0.001) or deciding to skip their medication (Unadjusted OR 2.01 95% CI 1.44-2.82, P < 0.001), suggesting that PTSD serves as a significant risk factor for both unintentional and intentional medication nonadherence.13

With regard to unintentional medication adherence, PTSD can disrupt an individual’s short and long-term memory by causing changes in associated brain regions, such as the hippocampus, amygdala, and pre-frontal cortex.14 One of the hallmarks of PTSD’s impact on general memory includes increased forgetfulness, which may increase individuals’ risk of forgetting to take their medication.13, 14, 15

For intentional medication adherence, a series of barriers exist that may prevent individuals from taking their medications as prescribed. Concerns over treatment, the lack of providers with expertise in PTSD, stigma, poor prior experiences with the healthcare system, and pride in perceived self-efficacy and self-reliance have all been reported as barriers to individuals seeking treatment for PTSD.16 Among combat veterans, many expressed concern about taking psychiatric medication to alleviate their symptoms due to the overarching stigma associated with their use.16, 17 Concern over stigmatizing labels associated with a PTSD diagnosis (and mental health conditions more broadly) have also presented as significant barriers to those considering seeking treatment.16 Moreover, a desire to manage PTSD symptoms independently, along with a sense of comparative insignificance– in which individuals believe others need more help than them– have also been highlighted as reasons why some who meet the diagnostic criteria for PTSD avoid seeking treatment.16

Despite these barriers, strong evidence suggests the benefits of various medications in helping to treat PTSD, such as fluoxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine XR, etc., with studies indicating symptom improvement in 35% of people who did not take anti-depressants v. 55% who did, showing a 20% improvement.18, 19 This highlights the potential benefits of such medications in alleviating symptoms of irritability, depression, anxiety, and insomnia in those with PTSD.18 However, it is important to consider that anti-depressants often have a delayed onset, meaning it can take up to 6 weeks before a patient experiences the benefits of the treatment.18 This lack of immediate benefit, in addition to the various unpleasant side effects associated with these medications (such as nausea, headaches, and dizziness), can make it even more challenging for patients to continue taking their medication as prescribed.20 While the previous barriers listed for intentional nonadherence may decrease the likelihood of patients seeking or beginning treatment, it is critical to consider that even for those who do, the impact of SSRIs presents a series of additional challenges that make remaining on treatment increasingly challenging.

Improving Medication Adherence Among Patients with PTSD

Despite increasing recognition of the challenges facing individuals with PTSD from seeking, initiating, and continuing medication, little research has focused on specific strategies to enhance it. However, various guidelines from the National Institute of Mental Health,21 and additional resources, offer insight into potential strategies for supporting those with PTSD that can be extended to include supporting those who are prescribed medications to remain adherent.

- Offer Support

Emotional support is critical for supporting those with PTSD and for enhancing medication adherence.21, 22 Having a strong social support system, including support from healthcare providers, family, and friends, has been associated with an increased likelihood of treatment initiation for those with PTSD.16 Likewise, research has found that social support enhances medication adherence across various conditions.23

- Establish a Consistent Routine

PTSD can significantly impair an individual’s memory formation, memory recall, and working memory, leading to increased forgetfulness and difficulty remembering to complete everyday tasks–such as taking medication.14, 21 Healthcare providers should aim to integrate a patient’s medication dosing regimen into their daily routine in a way that promotes habit formation, reducing the need for conscious effort, and improving medication adherence.24 Moreover, medication reminders may prove useful in combating forgetfulness if they gently remind patients to take their medication.25 When implementing this, it is important to take the patient’s triggers into account. Identifying these triggers and customizing reminders to patient preference is essential to ensure empathetic and patient-centered support.21

- Therapeutic Alliance and Setting Realistic Expectations

As noted, anti-depressants are the common line of medication used in PTSD treatment, but such medications can take up to 6–8 weeks for noticeable improvements to be identified.26 This delayed onset of action, in addition to unpleasant side effects, can be discouraging and increase the risk of nonadherence. Providers should set realistic expectations early on in treatment, explaining the importance of remaining adherent to see potential long-term benefits. Similarly, providers should work to foster a strong therapeutic alliance with patients, in which the provider builds a collaborative and trusting relationship with their patients.27 This helps to ensure patients feel heard and supported, increasing the likelihood of them following their provider’s recommendations, such as taking their medication.28

- Challenge Stigma and Empower Patients

Procedures aimed at reducing societal stigma and internal stigma surrounding PTSD are essential for facilitating mental health treatment.16 For instance, believing that getting help is socially acceptable and that others’ negative views do not detract from the disorder and need for treatment, have been shown to increase the likelihood of individuals with PTSD seeking treatment.16, 29 Furthermore, providers should work with patients by discussing all available treatment options, including psychotherapy, medication, or a combination of both.16 By providing evidence-based information regarding the potential benefits of medication, in addition to psychotherapy, providers can increase patient’s trust and willingness to initiate or remain on their medication(s).

- Celebrate Milestones

Healing from trauma, and PTSD, is not linear, but acknowledging small wins is vital in building patient confidence and fostering motivation.30 Celebrating small wins, such as taking medication consistently for three days in a row, helps to reinforce the behavior, making patients more likely to continue engaging their treatment routine.30 Celebrations release chemicals–like dopamine– into the brain, which can enhance a patient’s mood and contribute to a more positive outlook on their treatment journey.30 Even small gestures, such as a message of congratulations for remaining adherent to medication, can serve as powerful reinforcements that help patients remain engaged and feel as though their progress has been recognized.

Additional Resources

- Looking for a mental health care provider, therapist, or counselor who specializes in PTSD treatment? Click here!

- How can I get help for myself or a loved one in a crisis?

Contact information for emergency resources such as the (988) Suicide and Crisis Lifeline and Veterans Crisis Line (988, press 1).

Resources for family and friends supporting a loved one with PTSD? Click here!

References

1 Mayo Clinic. (2024, September). Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – Symptoms and causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/post-traumatic-stress-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20355967

2 World Health Organization. (2024, May 27). Post-traumatic stress disorder. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/post-traumatic-stress-disorder

3 Koenen, K. C., Ratanatharathorn, A., Ng, L., McLaughlin, K. A., Bromet, E. J., Stein, D. J., … & Kessler, R. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the world mental health surveys. Psychological medicine, 47(13), 2260-2274.

4 Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US). Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2014. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 57.) Chapter 3, Understanding the Impact of Trauma. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207191/

5 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2025, May 31). Myth: All Veterans Have PTSD. https://www.va.gov/vetsinworkplace/training/EAP/lesson04/04_003_hs01.htm

6 National Veterans Foundation. (2017, January 24). Transitioning from military to civilian: The unique challenges of female veterans. National Veterans Foundation. https://nvf.org/transitioning-female-veterans/

7 Friedman, J. K., Taylor, B. C., Campbell, E. H., Allen, K., Bangerter, A., Branson, M., … & Burgess, D. J. (2024). Gender differences in PTSD severity and pain outcomes: Baseline results from the LAMP trial. Plos one, 19(5), e0293437.

8 Olff, M. (2017). Sex and gender differences in post-traumatic stress disorder: an update. European journal of psychotraumatology, 8(sup4), 1351204.

9 Jacobs, A. (2024, June 4). F.D.A. panel rejects MDMA-aided therapy for PTSD. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/04/well/ptsd-treatment-mdma.html

10 Bruce, S. E., Weisberg, R. B., Dolan, R. T., Machan, J. T., Kessler, R. C., Manchester, G., … & Keller, M. B. (2001). Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care patients. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 3(5), 211.

11 Williams, A. A. (2019, June 12). Posttraumatic stress disorder: Often missed in primary care. The Journal of Family Practice, 66(10), 618-623. https://blogs.the-hospitalist.org/content/posttraumatic-stress-disorder-often-missed-primary-care

12 Henley, M. (2023, May 15). When PTSD goes untreated: The hidden dangers and long-term effects. Animo Sano Psychiatry. https://animosanopsychiatry.com/when-ptsd-goes-untreated-the-hidden-dangers-and-long-term-effects/

13 Kronish, I. M., Edmondson, D., Li, Y., & Cohen, B. E. (2012). Post-traumatic stress disorder and medication adherence: results from the Mind Your Heart study. Journal of psychiatric research, 46(12), 1595-1599.

14 Lockett, E. (2023, March 24). Living with Memory loss as a symptom of PTSD. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/mental-health/memory-loss-and-ptsd#causation

15 Roberts, A. L., Liu, J., Lawn, R. B., Jha, S. C., Sumner, J. A., Kang, J. H., Rimm, E. B., Grodstein, F., Kubzansky, L. D., Chibnik, L. B., & Koenen, K. C. (2022). Association of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder With Accelerated Cognitive Decline in Middle-aged Women. JAMA network open, 5(6), e2217698. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.17698

16 Smith, J. R., Workneh, A., & Yaya, S. (2019). Barriers and facilitators to help‐seeking for individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(2), 137-150. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22456

17 Mittal, D., Drummond, K. L., Blevins, D., Curran, G., Corrigan, P., & Sullivan, G. (2013). Stigma associated with PTSD: Perceptions of treatment seeking combat veterans. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 36(2), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0094976

18 InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Learn More – Medication for post-traumatic stress disorder. [Updated 2023 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532841/

19 Schrader, C., & Ross, A. (2021). A review of PTSD and current treatment strategies. Missouri medicine, 118(6), 546–551.

20 Chu A, Wadhwa R. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554406/

21 National Institute of Mental Health.(2023). Post-traumatic stress disorder(NIH Publication No. 23-MH-8124). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/health/publications/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd/post-traumatic-stress-disorder_1.pdf

22 Reblin, M., & Uchino, B. N. (2008). Social and emotional support and its implication for health. Current opinion in psychiatry, 21(2), 201-205.

23 Scheurer, D., Choudhry, N., Swanton, K. A., Matlin, O., & Shrank, W. (2012). Association between different types of social support and medication adherence. The American journal of managed care, 18(12), e461-7.

24 Hassett, T. C., & Hampton, R. R. (2017). Change in the relative contributions of habit and working memory facilitates serial reversal learning expertise in rhesus monkeys. Animal cognition, 20(3), 485-497.

25 Gleeson, J. R. (2018, April 19). 8 easy ways to remember to take your medication. University of Michigain: Michigan Medicine. https://www.michiganmedicine.org/health-lab/8-easy-ways-remember-take-your-medication

26 Uher, R., Mors, O., Rietschel, M., Rajewska-Rager, A., Petrovic, A., Zobel, A., … & McGuffin, P. (2011). Early and delayed onset of response to antidepressants in individual trajectories of change during treatment of major depression: a secondary analysis of data from the Genome-Based Therapeutic Drugs for Depression (GENDEP) study. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 72(11), 5274.

27 Solmi, M., Miola, A., Croatto, G., Pigato, G., Favaro, A., Fornaro, M., … & Carvalho, A. F. (2020). How can we improve antidepressant adherence in the management of depression? A targeted review and 10 clinical recommendations. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 43, 189-202.

28 Keller, S. M., Zoellner, L. A., & Feeny, N. C. (2010). Understanding factors associated with early therapeutic alliance in PTSD treatment: Adherence, childhood sexual abuse history, and social support. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(6), 974–979. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020758

29 Sayer, N. A., Friedemann-Sanchez, G., Spoont, M., Murdoch, M., Parker, L. E., Chiros, C., & Rosenheck, R. (2009). A qualitative study of determinants of PTSD treatment initiation in veterans. Psychiatry, 72(3), 238-255.

30 DVAP Riverside. (2024, November 21). Celebrating milestones and achievements in the healing journey. https://dvapriverside.org/celebrating-milestones-and-achievements-in-the-healing-journey/