The 1950s marked a pivotal moment in the history of public health, with the development and success of the polio vaccine trials leading to the near-eradication of a disease that had paralyzed and killed thousands each year1. The trials were not just a scientific triumph; they also offered valuable insights into the importance of promoting medication adherence and the lessons learned in conducting mass vaccination campaigns1. These lessons have had lasting implications for the way we approach public health challenges today, especially in how we conduct and promote modern vaccination efforts, like those during COVID-19.

In the United States alone, annual outbreaks of polio paralyzed thousands of children, in severe cases, the disease carried a high risk of death1. The vaccine trials, led by Dr. Jonas Salk in the early 1950s, represented a beacon of hope1. In 1954, the largest clinical trial in history at the time began, involving over 1.8 million children across the U.S2. The results of these trials were groundbreaking: the vaccine was shown to be highly effective in preventing polio2. By 1961, the polio vaccine had become widely available, leading to a dramatic reduction in cases1,2. The success of the polio vaccine is one of the most significant public health victories of the 20th century, saving countless lives and preventing lifelong disabilities1,2.

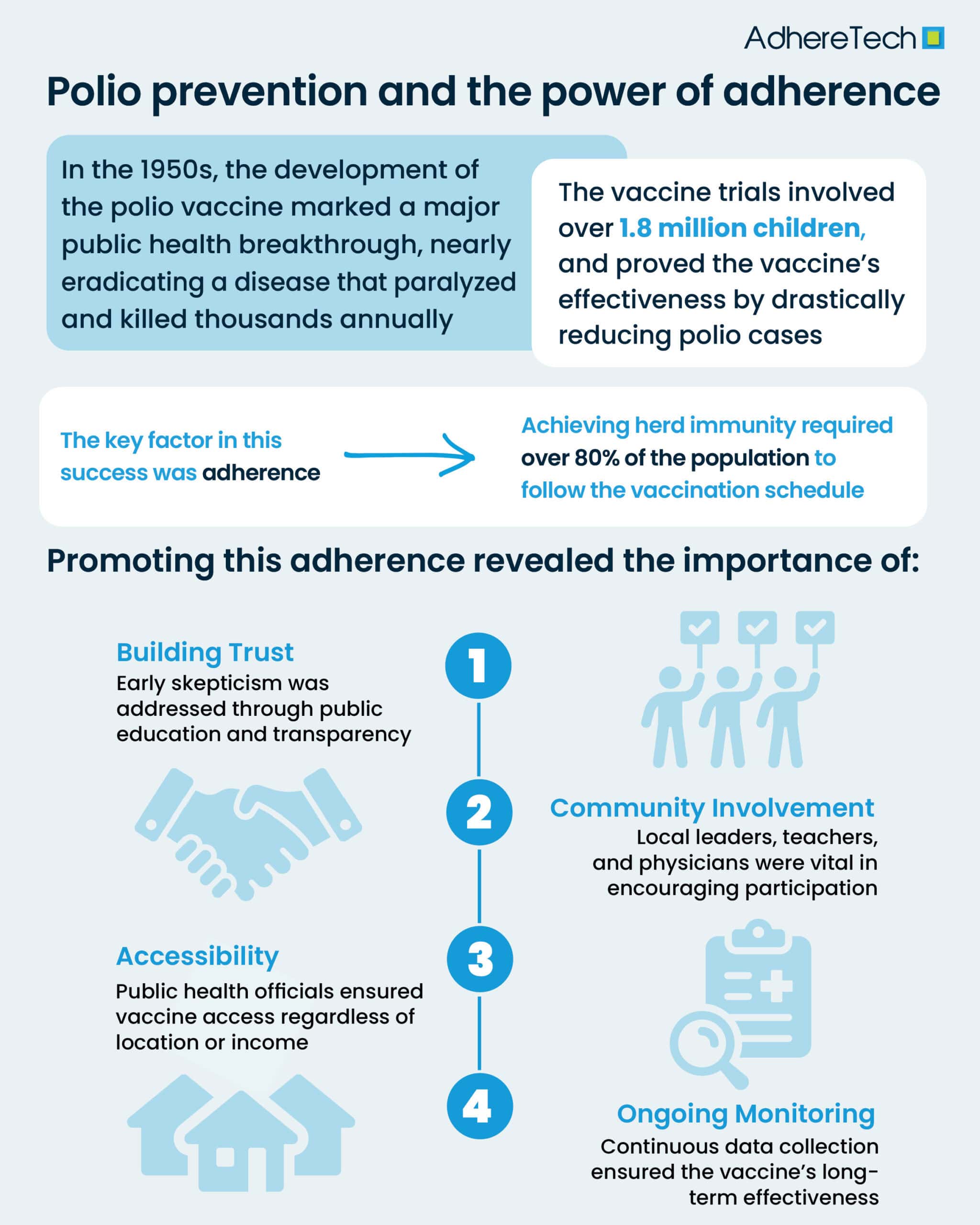

While the polio vaccine’s scientific success is well-remembered, the success of mass vaccination campaigns were significantly influenced by one crucial factor: adherence3. For the vaccine to work on a large scale, it was not enough for just a few people to get vaccinated. To guarantee “herd immunity,” public health officials had to ensure that the vaccine reached at least 80% of entire communities or populations, and that they remained consistently adherent to the designated vaccination schedule4.

In the case of the polio vaccine, several key lessons emerged in promoting adherence to mass vaccination efforts. These lessons have since shaped our approach to vaccination campaigns, both during the polio era and in the present day. One of the most important lessons from the polio vaccine trials was the necessity of building public trust5. Early in the 1950s, there was a significant amount of skepticism and fear surrounding new vaccines and treatments5. To address these concerns, health authorities, including the U.S. Public Health Service took proactive steps to educate the public about the safety and effectiveness of the existing treatments6.

Dr. Salk himself famously stated, “The people’s choice,” when asked who owned the patent for the vaccine, implying that the vaccine should belong to the public and not be commercialized for profit7. This transparency helped alleviate concerns and fostered a sense of shared responsibility in the fight against polio, enhancing the general public’s adherence to the vaccine5.

In modern vaccination efforts, such as with COVID-19, similar approaches to building trust are essential. Public health campaigns must focus on clear communication, addressing misinformation, and educating the public about the benefits and safety of vaccines. The success of the polio vaccine was also influenced by the strong involvement of local communities8. From the very beginning of the trials, local physicians, teachers, and community leaders were enlisted to help promote the vaccine and encourage children and families to participate8. Partnering with trusted community members to enhance community engagement plays a crucial role in overcoming barriers of distrust and logistical challenges.

Similarly, modern vaccination campaigns have benefited from community-level engagement. In regions with vaccine hesitancy, local leaders, including religious figures and influencers, are often crucial in helping to sway public opinion and encourage participation9. Engaging communities not only improves adherence but also helps tailor vaccination strategies to the specific needs and concerns of different populations.

One of the greatest challenges in ensuring widespread vaccine adherence is accessibility10. During the polio vaccine trials, public health officials worked to make the vaccine accessible to all children, regardless of socioeconomic status11. This meant reaching rural areas, organizing mass vaccination sites, and ensuring that those who needed the vaccine most could access it11. Today, the lessons learned from polio vaccine distribution are evident in the efforts to ensure equitable access to vaccines. Pop-up vaccination clinics to mobile units traveling to underserved communities help to make vaccines accessible and convenient, which is crucial for maximizing adherence rates11.

After the success of the initial polio vaccine trials, ongoing surveillance was essential in monitoring the vaccine’s impact and ensuring its effectiveness12. The rapid feedback loop from healthcare professionals and the general public allowed for quick responses to emerging concerns, such as the need for booster doses. Today, the concept of continuous monitoring remains integral to vaccine campaigns12. Monitoring vaccine safety and efficacy, tracking adverse events, and adapting strategies based on real-time data are essential to maintaining high levels of adherence and ensuring long-term success2,12.

The polio vaccine trials in the 1950s were a remarkable achievement, not just in terms of scientific innovation, but also in the lessons they taught us about public health campaigns. Ensuring widespread vaccine adherence requires trust-building, community involvement, accessibility, institutional support, and continuous feedback. These same principles continue to guide modern vaccination efforts, as we tackle current challenges like COVID-19 and other vaccine-preventable diseases.

As we move forward, the success of the polio vaccine reminds us that public health victories are not just about the science — they are about the people. With the right approach, we can overcome barriers to medication adherence, protect vulnerable populations, and continue to make strides in the global fight against infectious diseases.

References

- World Health Organization. “History of Polio Vaccination.” World Health Organization, World Health Organization, 2021, www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/history-of-vaccination/history-of-polio-vaccination.

- Meldrum, Marcia. ““A Calculated Risk”: The Salk Polio Vaccine Field Trials of 1954.” BMJ, vol. 317, no. 7167, 31 Oct. 1998, pp. 1233–1236, www.bmj.com/content/317/7167/1233.full, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.317.7167.1233.

- Sutter, R. W., and C. Maher. “Mass Vaccination Campaigns for Polio Eradication: An Essential Strategy for Success.” Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology, vol. 304, 2006, pp. 195–220, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16989271/, https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-36583-4_11.

- Breen, Tom. “Polio Vaccination Rates in Some Areas of the US Hover Dangerously close to the Threshold Required for Herd Immunity – Here’s Why That Matters.” UConn Today, 27 Sept. 2022, today.uconn.edu/2022/09/polio-vaccination-rates-in-some-areas-of-the-us-hover-dangerously-close-to-the-threshold-required-for-herd-immunity-heres-why-that-matters-2/.

- Pavia, Charles S, and Maria M Plummer. “Lessons Learned from the Successful Polio Vaccine Experience Not Learned or Applied with the Development and Implementation of the COVID-19 Vaccines.” Current Opinion in Immunology, vol. 84, 1 Oct. 2023, p. 102386, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S095279152300105X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2023.102386.

- Ozawa, Sachiko, and Meghan L Stack. “Public Trust and Vaccine Acceptance-International Perspectives.” Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, vol. 9, no. 8, 8 Aug. 2013, pp. 1774–1778, https://doi.org/10.4161/hv.24961.

- Tan, Siang Yong, and Nate Ponstein. “Jonas Salk (1914–1995): A Vaccine against Polio.” Singapore Medical Journal, vol. 60, no. 1, Jan. 2019, pp. 9–10, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6351694/, https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2019002.

- Closser, Svea, et al. “The Impact of Polio Eradication on Routine Immunization and Primary Health Care: A Mixed-Methods Study.” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 210, no. Suppl 1, 1 Nov. 2014, pp. S504–S513, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4197907/, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jit232.

- Sinuraya, Rano K, et al. “Vaccine Hesitancy and Equity: Lessons Learned from the Past and How They Affect the COVID-19 Countermeasure in Indonesia.” Globalization and Health, vol. 20, no. 1, 6 Feb. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-023-00987-w.

- Galagali, Preeti M., et al. “Vaccine Hesitancy: Obstacles and Challenges.” Current Pediatrics Reports, vol. 10, no. 4, 8 Oct. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40124-022-00278-9.

- Millward, Gareth. Poliomyelitis. Www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, Manchester University Press, 2019, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545991/.

- Harutyunyan, Vachagan, et al. “Securing the Future: Strategies for Global Polio Vaccine Security amid Eradication Efforts.” Vaccines, vol. 12, no. 12, Dec. 2024, p. 1369, www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/12/12/1369, https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12121369.