The Obesity Epidemic within America

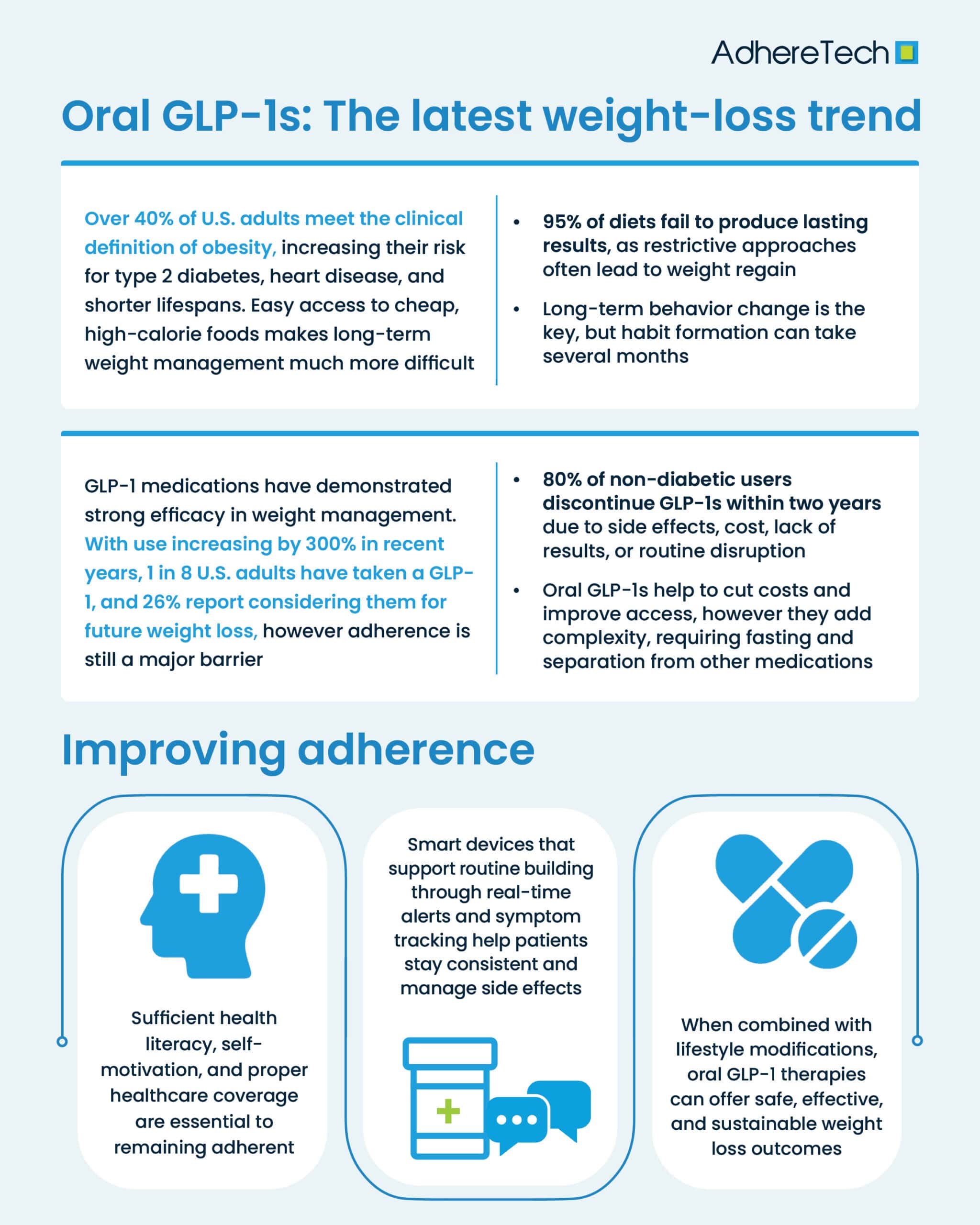

According to the CDC, as of August 2023, the prevalence of obesity in American adults was 40.3%, over a two-and-a-half-fold increase from 1976 (an estimated 15%), providing evidence of the growing obesity rates within modern America (Emmerich et al., 2024; Temple, 2022). Obesity is defined as an adult with a body mass index (BMI), which exceeds 30% or “excess body fat,” that increases one’s risk of developing numerous serious physical and mental health conditions (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2023). For example, roughly 90% of individuals diagnosed with Type II diabetes are considered obese or overweight, in comparison to only 9.4% of the total United States population receiving a Type II diabetes diagnosis (American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, 2018). Likewise, carrying additional weight can also increase one’s risk of high blood pressure, metabolic syndrome, stroke, heart disease, and other chronic illnesses (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2023).

The effects of obesity extend beyond physical consequences, which can also negatively impact an individual’s mental health. The heightened risk of low self-esteem, depression, eating disorders, etc., can all arguably be just as detrimental as the physical effects of obesity on one’s quality of life. (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2023). With a life expectancy as much as 14 years shorter than an individual in the healthy BMI range, the consequences of obesity can be exceptionally grave (Obesity Medicine Association, 2024).

Although there is increased recognition regarding the negative impacts of obesity on one’s emotional and physical well-being, losing weight remains challenging for many Americans. The United States obesity epidemic arguably began in 1970 driven by reduced trade restrictions and the increased availability and affordability of high-calorie, oversized processed foods (Klein, 2004). The epidemic has continued, as evidenced by recent research emerging from Philadelphia which found that their food portions were four times larger than those served in Paris, and significantly larger than typical portion sizes in the U.S. during the 1950s (Awan, 2023).

Notably, the high cost of nutritious and unprocessed foods serves as a major barrier for those attempting to alter their diet, leaving people with little option but to purchase fast food options that are higher in calories and lower in nutritional value (Awan, 2023). For instance, “value meals” from fast food chains, which offer low-priced, calorically dense foods have become a nightly staple for many Americans due to their convenience and affordability (Awan, 2023). In fact, 65% of Americans report eating fast food at least once a week and 36.6% reported consuming fast food daily (Fryar et al., 2018; Rogers, 2023).

The predominant issue with many of these ultra-processed foods is that they are typically low in nutrients and fiber, which translates into rapid spikes and crashes in blood sugar which reduce satiety (Sweney, 2024). Hence, despite often being high in caloric value, these foods lack substantial energy, resulting in the need to consume more food (and calories) to feel properly full.

Interestingly, these foods may also impair the functioning of dopaminergic pathways, with the potential to alter reward processing (Volkow et al., 2011). Foods high in sugar and unhealthy fats have been shown to increase dopamine release, however, when these foods are consumed on a frequent basis, this can reduce the functioning of dopamine receptors by desensitizing them (Luengo et al., 2024). This can create a positive feedback loop, in which individuals experience heightened cravings for more of such foods in order to compensate for this decreased reward stimulation (Luengo et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2001).

America’s Obsession & Challenges with Weight Loss

Weight loss is and has been a long-withstanding challenge within American society, with fad diets beginning as early as the 19th century (Harbster, 2015). Over the years various diets have been promoted and fluctuated in popularity. However, the overarching issue with the majority of them is that they involve a heavy restriction on certain food groups or eating windows (Rissetto, 2022). While these diets can provide quick weight loss results, they can lead to deprivation and nutrient deficiencies that make them unsustainable in the long term (Rissetto, 2022). Beyond the challenges imposed by these diets, additional factors, ranging from 400 genes linked to an increased risk of obesity and weight gain to reductions in metabolism and increased ghrelin (hunger) levels when losing weight, all make it exceptionally challenging for individuals to lose weight, and keep it off in the long-run (Northwestern Medicine, 2022).

As a result, it is not unsurprising that research indicates that 95% of diets fail to result in long-term weight loss, and as many as 90% of people who lose a substantial amount of weight will end up gaining it back, often due to individuals returning to their normal eating patterns after weight loss (Northwestern Medicine, 2022; Utah State University, 2018). The frequent cycle of repeated weight loss and gain is often referred to as “yo-yo” dieting (Thillainadesan et al., 2024). One of the biggest factors contributing to the failure of these diets to translate into long-term, substantial weight loss? Low adherence (Cruwys et al., 2020). In fact, research has found that diets motivated by weight control negatively predict adherence (β = −0.18, p = 0.001) (Cruwys et al., 2020).

Long-term lifestyle changes are necessary for sustained weight loss, however, research highlights it takes an estimated 66 days to form a new habit, but can take as long as eight months for habit formation (Northwestern Medicine Center, 2022; Schimelpfening, 2024). Nutritionists indicate that lifestyle changes are more challenging when they are entirely new to an individual as opposed to building on an existing behavior (Schimelpfening, 2024). Hence, it may be increasingly difficult for individuals to stick to a new diet if it entails a complete elimination mindset and the introduction of entirely new foods.

Given the persistent challenges of maintaining weight loss through diet alone and the increasing prevalence of obesity, attention has shifted toward other interventions, such as those focused on addressing the biological mechanisms that underlie appetite and metabolism. For instance, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), is a naturally produced hormone that is critical for regulating blood sugar levels and appetite (Müller et al, 2019). In 2005, the first GLP-1 agonist was approved by the FDA for Type II diabetes, a medication that mimics the action of GLP-1 to help control blood sugar levels (Dorrell, 2024).

Clinicians began to notice the additional weight management benefits of these medications in addressing metabolic syndrome in patients diagnosed with diabetes and patients with conditions exacerbated by being overweight or obese (Moorman, 2024). Consequently, the first GLP-1 agonist for weight loss was approved in 2015 (Sanders, 2022). New products have continued to be approved, particularly between 2018 and 2023, resulting in prescriptions for these medications increasing by 300%, with over 12% of adults reporting having taken a GLP-1 drug as of 2023 (Dorrell, 2024; Montero et al., 2024). To put this into perspective, an estimated one in every eight adults reported taking a GLP-1 as of 2023 (Montero et al., 2024). And as of 2025, Forbes found that 26% of Americans (roughly 1 in every 4) reported planning on using GLP-1 medications for weight loss (Valloppillil, 2025).

However, much like how adherence poses a significant challenge to successful weight loss via diets, it remains a significant issue with GLP-1s. Using these medications exclusively for weight loss seems to also predict higher rates of nonadherence, with Rodriguez et al., 2025 finding that discontinuation rates for GLP-1 receptor agonists “were significantly lower for patients with Type II diabetes (46.5% [95% CI, 46.2%-46.9%] by 1 year and 64.1% [95% CI, 63.7%-64.5%] by 2 years) compared with patients without Type II diabetes (64.8% [95% CI, 64.4%-65.2%] by 1 year and 84.4% [95% CI, 84.0%-84.8%] by 2 years)”. Notably, various factors are believed to influence these high nonadherence rates including hesitation regarding self-administering injections, stopping medications if weight loss is not immediate, unpleasant gastrointestinal side effects, and financial concerns given the high out-of-pocket costs and variable in-network costs associated with these medications (Shields Health Solutions, 2025).

To alleviate existing issues with these injectable medications, numerous companies are working to release oral GLP-1’s, with the aim of reducing GLP-1 shortages and the cost of these medications, while enhancing convenience (Tirrell, 2024). However, the oral versions of these medications also come with a series of potential challenges for medication adherence. For one, oral semaglutide must be taken at least 30 minutes before any food, beverage, or other oral medications for full efficacy (Hughes & Neumiller, 2020; Seo, 2025). This may prove challenging, especially for patients who are recommended to take other medications first thing in the morning on an empty stomach (Hughes & Neumiller, 2020). Attempting to manage multiple time-sensitive medications can disrupt an individual’s daily routine, increasing the risk of missing medications or consuming them outside of the recommended dosing window for full efficacy.

Moreover, when oral semaglutide was coadministered with thyroxine, thyroxine levels were shown to increase by up to 33%, raising concerns about potential drug interactions (Hughes & Neumiller, 2020). Elevated thyroxine levels can lead to dangerous heart symptoms, such as arrhythmias and tachycardia (Cleaveland Clinic, n.d.). Additionally, semaglutide is associated with over 270 medications that have known interactions, while Mounjaro has 415 such listings (Drugs.com, 2025) These uncertain or adverse drug interactions—and even the fear of them—may prompt patients or providers to discontinue GLP-1 therapies.

The dose of oral semaglutide for obesity is much higher (25–50mg daily) versus the injectable semaglutide (2.4mg weekly), which doctors have suggested oral GLP-1s run the risk for more pronounced side effects (Tirrell, 2024). This is particularly problematic given that in real-world studies, between 40 and 70% of patients have reported adverse GI events, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, with an injectable GLP-1 (Goodwin, 2025). While the vast majority of side effects reported for the oral semaglutide by Novo Nordisk are “mild to moderate and diminished over time,” experiencing adverse effects or fear regarding potential adverse effects to any drug has been shown to deter adherence to that medication (Baryakova et al., 2023). This highlights the importance of managing patients’ expectations and providing support to ensure patients have the resources in place to remain adherent to their treatment plan.

The concern with GLP-1s being promoted as short-term fixes, as opposed to long-term treatment methods, is also problematic. While GLP-1s may offer short-term benefits, these are unlikely to be sustained without ongoing use (Neale, 2024). Hence, while oral GLP-1s may increase access and usability for those with concerns over injections, adherence is likely to remain a prominent issue. Furthermore, implementation and adherence to a life-long sustainable diet, exercise regimen, and lifestyle modifications is essential for ensuring that when a patient begins to transition off of their medication, they have the established habits and behaviors in place to allow for weight maintenance.

With research indicating that stopping treatment with GLP-1 agonists within a year can lead to rebounds in body weight, loss of additional benefits, and potential worsening of cardiometabolic measures, helping patients remain adherent for the designated time period they are intended to take a GLP-1 is fundamental (Neale, 2024). Furthermore, implementation and adherence to a life-long sustainable diet, exercise regimen, and lifestyle modifications is essential for ensuring that when a patient begins to transition off of their medication, they have the established habits and behaviors in place to allow for weight maintenance. This poses the question: How can we improve adherence while patients are on GLP-1s?

Although no oral GLP-1 has currently been approved by the FDA for weight loss, numerous clinical trials are in their final phases and offer promising results that seem to suggest these drugs expect action dates from the FDA by the end of 2025 (Manalac, 2025; Tirrell, 2024). Research has already indicated low adherence to injectable GLP-1s when used for weight management, and highlighted particular concerns regarding adherence to daily injectables compared to weekly. One study found that 50.1% of patients discontinued daily GLP-1 receptor agonists, compared to 44.1% for weekly formulations (p < 0.001) (Kassem et al., 2024). Oral formulations presenting additional adherence barriers beyond a daily dosing regimen, including a strict dosing schedule, possible drug interactions, and the potential for increased development and/or intensity of side effects, may further complicate consistent use (Hughes & Neumiller, 2020; Tirrell, 2024).

Potential Barriers to Remaining Adherent to GLP-1s

A review of prescription medication adherence in chronic condition treatment highlights that a series of patient, illness, medication, healthcare system, and logistical and financial barriers exist that reduce adherence among patients with chronic conditions, including obesity, which has been classified as a complex chronic condition by the World Health Organization (2025) (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). Addressing these barriers is critical for promoting adherence, which presents a significant concern for anti-obesity medications.

Patient-Specific Barrier

Patients who experience changes in their routine and high stress may particularly struggle with remaining adherent to their medications (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). When considering oral GLP-1s, which will require patients to take their medication on an empty stomach without consuming any other oral medications, in addition to food or beverages for at least 30 minutes, this may significantly disrupt many patients’ existing daily routines. For instance, this may require individuals to wake up earlier to fit this medication into their daily routine, which is particularly problematic given that research indicates obesity can already heighten sleep disturbances (Jetpuri & Khan, 2022).

Moreover, 67.2% of US adults with obesity reported having at least one comorbidity (Marck et al., 2016). For individuals required to take other medications on an empty stomach, taking an oral GLP-1 may throw off their existing medication routine, causing them to forget to take their other medications after this 30 minute window.

Notably, patients on bisphosphonates, used to treat osteoporosis, are required to take their medication 30 minutes before their first food, drink, or medication of the day (Hannemann & Ulrich, 2024). One study found that orange juice lowered medication absorption rates by up to 60%, highlighting the importance of adhering to this dosing regimen (Hannemann & Ulrich, 2024). Another study found that for patients on weekly and monthly oral bisphosphonates, only 44% reported complying with all dosing instructions (Vytrisalova et al., 2015). Additional research found that significantly more patients with a weekly bisphosphonate dosing routine (about 50%) were adherent than those on the daily dosing schedule (about 33%) (Recker et al., 2005). These findings suggest that similarly complex routines for oral GLP-1s may pose comparable risks for nonadherence.

Additionally, the common gastrointestinal effects of GLP-1s may further disrupt daily routines, such as causing individuals to take time off work or avoid activities that may worsen their symptoms. These disruptions can heighten stress and reduce motivation to remain adherent, especially when the discomfort and disruptions outweigh the perceived long-term benefits.

Medication-Specific Barriers

A lack of information or trust, as well as regimen complexity, can further deter patients from taking their medications as prescribed (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). If patients are not properly informed of the associated side effects of GLP-1s, the time these take to resolve, and the need for consistency in order to see long-term sustained weight loss, they may discontinue their medication prematurely (Mayo Clinic, n.d.).

Moreover, a lack of trust in healthcare providers may make patients more hesitant to take these medications (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). For instance, if a patient has received previous weight loss regimens from their provider that have proved ineffective, they may be hesitant to believe a new regimen involving medication will have any substantial benefits.

The complexity of oral GLP-1 regimens, due to the timing at which they must be consumed for full efficacy, may further increase patients’ difficulty of following their provider’s instructions (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021).

Illness-specific Barriers

A lack of awareness regarding the potential consequences of obesity due to a lack of symptoms can be particularly detrimental when considering adherence to GLP-1s (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). While obesity can increase one’s risk of developing various chronic conditions (ex: cardiovascular disease,Type II diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders, and some types of cancer), there are no specific symptoms directly related to obesity (World Health Organization, 2024). For instance, some individuals may be classified as “obese,” but are considered “metabolically healthy,” with no co-existing chronic health conditions (Muñoz-Garach et al., 2016). The absence of immediate health issues may contribute to a false sense of security. However, risk of coronary heart disease and heart failure increases by 46% and 96% respectively, even for obese individuals with no signs of metabolic disease, abnormal blood pressure, cholesterol, or diabetes (Medical News Today Team, 2022). The lack of symptoms directly tied to obesity or a perceived sense of urgency may result in individuals not prioritizing weight loss, highlighting a critical illness-specific barrier to prevention and treatment. This low perceived risk could contribute to poor adherence to prescribed medications, and the lifestyle modifications necessary to support weight loss on these medications, heightening the risk of long-term health consequences.

Healthcare System Barriers

Issues within the healthcare system itself may also present significant barriers to individuals taking their GLP-1 medications as prescribed (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). If communication between patients and providers is lacking, research has shown that the risk of nonadherence increases (Zolnierek & DiMatteo, 2010). For instance, if healthcare providers fail to communicate the common side effects associated with GLP-1s, such as gastrointestinal issues, patients may deem the medication as harmful and discontinue treatment without consulting their provider.

Additionally, a lack of support or follow-up from providers can leave patients feeling isolated in managing their condition, which may further decrease adherence to treatment (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). If providers do not provide clear guidance on the potential side effects, expected weight loss, or other outcomes associated with GLP-1 medications, patients may develop unrealistic expectations.This may lead to disappointment and a greater likelihood of discontinuing the medication. Similarly, if providers are unavailable to address patients’ concerns or questions, it may exacerbate feelings of uncertainty and reduce motivation to continue treatment.

Logistical and Financial Barriers

Among the most frequently cited issues with GLP-1s in the media are their high costs and national shortages (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021. Although the FDA recently announced the resolution of the GLP-1 injection shortage, this shortage, largely due to an unexpected increase in demand without an adequate increase in production, lasted for over two years (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2025; Whitley et al., 2023). The rapid rise in demand resulted in substantial delays in access, insurance coverage denials, and increased strain on pharmacies and mail-order services trying to meet patient demand (Morris & Garritano, 2024). Interestingly, the production of oral GLP-1s is considerably simpler than subcutaneous injections, suggesting oral formulations may help to reduce supply chain concerns. However, industry experts have cautioned that widespread availability of oral GLP-1s may still require some time to fully realize.(Goodwin, 2024; Mattingly II et al., 2025).

Arguably, the larger issue with oral GLP-1s lies in their high costs. Notably, the list price for GLP-1s for both those with and without insurance is relatively high (GoodRx, n.d.; Klein, 2024). Consequently, it’s relatively unsurprising that a study from the Journal of the American Medical Association found that the lack of affordability of these medications presents a significant challenge: many of the people who would benefit from these medications, cannot access them due to their cost (Hwang et al., 2025). In order to be considered cost-effective, the net-price of existing GLP-1s would need to drop significantly (82% for Wegovy and 30% for Zepbound respectively) (Cohen, 2025). The ongoing high medication costs associated with GLP-1s may discourage or prevent continued adherence (Shield Health Solutions, 2025).

Moreover, due to the high costs of these drugs, insurance coverage is becoming increasingly less common for those intending to use it exclusively for weight loss, adding an additional barrier (Tong, 2025). For example, as of April 2025, Medicare and Medicaid will not be extended to cover weight loss drugs (Tin, 2025). Even for those with private insurance, many insurance providers will not cover prescription medications used exclusively for weight loss purposes (Morris, 2024). While the price of oral GLP-1s for weight loss have not yet been released, as these formulations are still awaiting FDA approval, they are still expected to be relatively expensive without insurance coverage (McKeown, 2022).

How to Enhance Medication Adherence for GLP-1s

While a series of barriers may present challenges to remaining medically adherent for those taking GLP-1s, targeted interventions can enhance adherence, and subsequently, patient health outcomes, for those with a chronic condition(s) (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). Facilitators can be broken down into five categories: information and knowledge, motivation, behavioral skills, and healthcare and system-specific factors (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). Although medication adherence is related to individual behavior, various healthcare, and system-specific factors can also dramatically affect such behavior. Hence, considering each component that emerges due to the complex interplay of social-ecological elements in medication-taking behaviors is crucial.

Information and Knowledge

A key aspect of enhancing medication adherence is ensuring patients have a comprehensive understanding of their disease and their prescribed medication (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). Health literacy is often defined as the way in which individuals access, understand, and use health information to improve their well-being (Upton et al., 2025). Research suggests that possessing adequate levels of health literacy can significantly impact weight loss, weight management, and associated health outcomes (Upton et al., 2025). This is likely because when information is presented in a clear and understandable manner, patients are more likely to understand the risks of their condition and the potential benefits of treatment, empowering them to engage in behavioral change.

For instance, if a patient is informed by their provider of the long-term risks and consequences of obesity, such as cardiovascular disease or Type II diabetes, they may become more inclined to adhere to their prescribed treatment to avoid such detriments. Similarly, by explaining the side effects of GLP-1s to patients, patients may become less fearful of the medications’ side effects and less likely to discontinue their medication, as they have been previously informed such effects are a common occurrence and not a reason to stop taking their medication(s). Likewise, using auditory and visual cues can serve as a simple and universal reminder system for patients, eliminating the complexity that may come with text-based reminder platforms, which may include complex language, language barriers, or translational errors. Consequently, interventions targeted at enhancing health literacy measures for obesity may help to promote adherence to weight-loss regimens, including GLP-1s (Upton et al., 2025).

Motivation

Motivation plays a significant role in whether patients take their medications as prescribed and can be broken down into three sub-categories including perceived necessity, concerns, and social motivation (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). Patients must perceive a need to take their medication as instructed, whether this be to improve their health or prevent future complications that could arise due to their condition (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). For instance, if a patient diagnosed with obesity understands that a 5% reduction in their body weight can result in clinically meaningful changes, such as a reduction in their risk of developing other chronic conditions, this will likely increase their desire to take their medication (Kompaniyets et al., 2023). Similarly, fears of the potential impacts of obesity may also translate into increased motivation to remain adherent (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021).

Arguably, motivation is heavily influenced by social factors as well (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). For instance, having a healthcare provider available to provide support and guidance throughout a weight-loss journey can help to ensure patients feel supported and encouraged in following their weight-loss regimen despite the challenges they may encounter (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). Research indicates that consistent, positive communication throughout a patient’s weight loss journey is a critical component of success (Albury et al., 2023). With this in mind, systems that incorporate behavioral reinforcement—such as reminders, rewards, or social support—can enhance motivation in a less burdensome way. For instance, AdhereTech’s smart devices use positive reinforcement by celebrating adherence “streaks” and providing access to a seven-day care team, creating a reliable and motivational support structure for patients.

Behavioral skills

Although successful medication adherence requires a joint effort between patients and providers, a patient’s behavioral skills can significantly influence whether or not they take their medication (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). For one, self-efficacy plays an essential role in adherence, defined as an individual’s belief in his or her capacity to execute the necessary behaviors required to produce the desired action (American Psychological Association, n.d.; Bandura, 1977). If an individual lacks confidence in their ability to manage their medication due to forgetfulness, confusion, negative side effects, etc., they may be less likely to follow their treatment (Martos-Mendez, 2015). Meanwhile, if an individual feels confident in their ability to take their medication as prescribed, such as eliminating forgetfulness by using a reminder system, adherence is likely to increase. AdhereTech fosters self-efficacy by offering smart devices that send real-time reminders via a gentle glow and chimes, as well as personalized text messages and phone calls. These features help reduce the cognitive burden placed on patients as the sole ones responsible for remembering to take their medication, promoting confidence in managing their medication routine.

Similarly, integrating medication into patients’ existing routines can enhance adherence, by working with patients as opposed to against them (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). For instance, let us consider a theoretical scenario, in which a nurse, Katie, who works the 6 am to 6 pm shift, is prescribed an oral GLP-1. Katie began taking her medication immediately upon waking up at 4 am before heading out for her daily workout, eliminating worry regarding the 30-minute fasting period required for GLP-1s from impacting her routine. By integrating medication into her daily routine, Katie’s behavior has an increased likelihood of becoming a habitual part of her daily routine. AdhereTech is designed to support routine-building with its customizable and habit-reinforcement features. Patients can choose a dosing schedule that aligns with their daily point and offers positive reinforcement — such as adherence streaks — to help reinforce medication routines as habitual behaviors.

One’s ability to cope with the potential side effects of their medication is also essential (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). Someone who is able to maintain a positive outlook and push through the initial gastrointestinal symptoms of GLP-1s for the long-term benefits associated with weight loss is far more likely to continue taking them, than someone with a present-oriented negative outlook, in which they only focus on the short-term, poor side effects. To assist with the potentially unpleasant side effects associated with GLP-1s, AdhereTech offers access to a live support team seven days a week. Patients can report side effects and AdhereTech’s care team offers support and ensures they are connected with a professional to discuss their concerns, helping patients remain motivated during the more challenging stages of their treatment.

Ensuring administrational ease of one’s medication is also crucial for promoting adherence (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). Arguably, the development of oral GLP-1s was driven primarily by patient concerns about the inconvenience of injections, with the goal of making GLP-1 therapy easier and more accessible to administer. However, issues may persist given the rigid regimen associated with oral GLP-1s, including the need to take the medication on a completely empty stomach and then fasting for 30 minutes, as well as remembering to take the medication daily, when compared to the injectable version which only requires a weekly injection and no fasting. Once again, a reminder system that reduces forgetfulness and allows for customization to ensure patients adhere to these requirements is likely to assist those who end up on oral GLP-1s.

Finally, good communication with one’s healthcare professional is another key component (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). By remaining in honest and consistent communication with one’s provider, providers can offer support to manage a patient’s concerns or questions, answer any questions, and help to set realistic expectations for patients. Evidently, this also requires healthcare professionals to remain in good communication with their patients ,since ignoring patients’ pressing questions or concerns may lead to a heightened risk of medication discontinuation.

Healthcare and system-specific factors

Healthcare and system-specific factors play a major, externally-influencing role on a patient’s adherence (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). Evidently, healthcare can serve as a massive inhibitor or facilitator of accessing GLP-1s. Patients without any form of medical insurance are unlikely to be able to afford these medications, and even for those with health coverage, many insurance companies are unwilling to cover these high-cost medications (Shields Health Solutions, 2025). Hence, good healthcare coverage plays a central role in whether or not patients take their medication, since it influences whether they can access them or not. Luckily, AdhereTech’s care team works to connect patients with financial resources to ensure they can maintain access to their medication.

Relatedly, ensuring patients have enough time to get their medication is also important (Dietz, 2023; Kvarnström et al., 2021). Without reminders, patients may forget to request a new prescription of their medication or shortages in GLP-1s may prevent their access, forcing patients to become nonadherent. AdhereTech’s devices are able to detect when patients are running low on their medication, and will send them a reminder notification before their medication runs out. This helps to prevent patients from forgetting to re-fill their prescription, and from becoming unintentionally nonadherent.

Concluding Thoughts

While GLP-1s offer significant benefits for conditions like obesity and diabetes, their success largely depends on patients’ ability to stick with their prescribed regimens. Factors such as side effects, dosing convenience, cost, and supply availability all play a role in influencing adherence. Advances like the development of oral formulations aim to address some of these barriers, with the potential to possibly improve the patient experience and commitment to treatment. Ultimately, healthcare providers must work closely with patients to manage expectations, address concerns, and tailor therapies to enhance adherence—ensuring that the full benefits of GLP-1s can be realized for those who need them most.

References

American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. (2018). Type 2 diabetes and metabolic surgery fact sheet. American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. https://asmbs.org/resources/type-2-diabetes-and-metabolic-surgery-fact-sheet/

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Self‑efficacy. In APA Division 44 – Resources for education. https://www.apa.org/pi/aids/resources/education/self-efficacy

Awan, O. (2023, January 25). How obesity in the U.S. has grown and what to do about it. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/omerawan/2023/01/25/has-the-obesity-epidemic-gotten-out-of-hand-in-america/

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215.

Baryakova, T. H., Pogostin, B. H., Langer, R., & McHugh, K. J. (2023). Overcoming barriers to patient adherence: the case for developing innovative drug delivery systems. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 22(5), 387-409.

Bryant, S. (2015, January 30). Battling with the scale: A look back at weight‑loss trends in the U.S. Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business. Library of Congress. https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2015/01/battling-with-the-scale-a-look-back-at-weight-loss-trends-in-the-u-s/

Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Thyrotoxicosis: What it is, causes, symptoms & treatment. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21741-thyrotoxicosis

Cohen, J. P. (2025, March 17). At current prices, GLP‑1s aren’t cost‑effective, limiting access to patients. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/joshuacohen/2025/03/17/at-current-prices-glp-1s-arent-cost-effective-limiting-access-to-patients/

Cruwys, T., Norwood, R., Chachay, V. S., Ntontis, E., & Sheffield, J. (2020). “An important part of who I am”: the predictors of dietary adherence among weight-loss, vegetarian, vegan, paleo, and gluten-free dietary groups. Nutrients, 12(4), 970.

Dietz, W. H. (2023, August 31). Patient adherence to anti-obesity medications. STOP Obesity Alliance. https://stop.publichealth.gwu.edu/LFD-aug23

Dorrell, M. (2024, January). Rx history: The rise of GLP-1s. Innovative Rx Strategies. https://innovativerxstrategies.com/rx-history-glp1s/

Drugs.com. (2025a). Semaglutide interactions checker. https://www.drugs.com/drug-interactions/semaglutide.html#:~:text=There%20are%20274%20drugs%20known,moderate%2C%20and%201%20is%20minor.

Drugs.com. (2025b). Mounjaro interactions checker. https://www.drugs.com/drug-interactions/tirzepatide,mounjaro.html#:~:text=There%20are%20415%20drugs%20known,moderate%2C%20and%201%20is%20minor.

Emmerich, S. D., Fryar, C. D., Stierman, B., & Ogden, C. L. (2024, September). Obesity and severe obesity prevalence in adults: United States, August 2021–August 2023 (NCHS Data Brief No. 508). National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db508.htm

Fryar, C. D., Hughes, J. P., Herrick, K. A., & Ahluwalia, N. (2018, October). Fast food consumption among adults in the United States, 2013–2016 (NCHS Data Brief No. 322). National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db322.htm stacks.cdc.gov+5

GoodRx. (n.d.). GLP-1 agonist. GoodRx. https://www.goodrx.com/classes/glp-1-agonists?srsltid=AfmBOooAAVfxfIOCW0Bo4ggYqvuLYU9SSmrqQSAW-umTklrP_vfxCji8

Goodwin, K. (2024, March 28). Will oral weight‑loss drugs break open an already lucrative market? BioSpace. https://www.biospace.com/will-oral-weight-loss-drugs-break-open-an-already-lucrative-market/

Goodwin, K. (2025, March 10). GLP-1 side effects only one factor driving patient discontinuation rates. BioSpace. https://www.biospace.com/drug-development/glp-1-side-effects-only-one-factor-driving-patient-discontinuation-rates

Hannemann, K., & Ulrich, A. (2024, April 15). 11 medications that should be taken on an empty stomach. GoodRx. https://www.goodrx.com/drugs/medication-basics/taking-medication-empty-stomach

Hughes, S., & Neumiller, J. J. (2020). Oral semaglutide. Clinical Diabetes, 38(1), 109-111.

Hwang, J. H., Laiteerapong, N., Huang, E. S., & Kim, D. D. (2025, March). Lifetime health effects and cost-effectiveness of tirzepatide and semaglutide in US adults. In JAMA Health Forum (Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. e245586-e245586). American Medical Association.

Jetpuri, Z., & Khan, S. (2022, November 2). Sleep disorders and obesity: A vicious cycle. UT Southwestern Medical Center. https://utswmed.org/medblog/obesity-sleep-disorders/

Kassem, S., Khalaila, B., Stein, N., Saliba, W., & Zaina, A. (2024). Efficacy, adherence and persistence of various glucagon‐like peptide‐1 agonists: nationwide real‐life data. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, 26(10), 4646-4652.

Klein S. (2004). Fat land: how Americans became the fattest people in the world. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 113(1), 2.

Klein, H. E. (2024, May 16). Most insured adults still have to pay at least part of the cost of GLP-1 drugs. AJMC. https://www.ajmc.com/view/most-insured-adults-still-have-to-pay-at-least-part-of-the-cost-of-glp-1-drugs

Kvarnström, K., Westerholm, A., Airaksinen, M., & Liira, H. (2021). Factors contributing to medication adherence in patients with a chronic condition: a scoping review of qualitative research. Pharmaceutics, 13(7), 1100.

Luengo, N., Goldfield, G. S., & Obregón, A. M. (2024). Association between dopamine genes, adiposity, food addiction, and eating behavior in Chilean adult. Frontiers in Nutrition, 11,

Manalac, T. (2025, May 5). Novo’s Wegovy inches closer to becoming first FDA-approved GLP-1 weight-loss pill. BioSpace. https://www.biospace.com/fda/novos-wegovy-inches-closer-to-becoming-first-fda-approved-glp-1-weight-loss-pill

Marck, C. H., Neate, S. L., Taylor, K. L., Weiland, T. J., & Jelinek, G. A. (2016). Prevalence of comorbidities, overweight and obesity in an international sample of people with multiple sclerosis and associations with modifiable lifestyle factors. PloS one, 11(2), e0148573.

Martos-Mendez, M. J. (2015). Self-efficacy and adherence to treatment: The mediating effects of social support. Journal of Behavioral Social Sciences 7(2). https://doi.org/10.5460/jbhsi.v7.2.52889

Mattingly, T. J., & Conti, R. M. (2025, January). Marketing and Safety Concerns for Compounded GLP-1 Receptor Agonists. In JAMA Health Forum (Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. e245015-e245015). American Medical Association.

Mayo Clinic. (2024, January 7). How fast does semaglutide kick in?. https://diet.mayoclinic.org/us/blog/2024/how-fast-does-semaglutide-kick-in/

McKeown, L.A. (2022, October 5). Sky-high cost of SGLT2i and GLP1 agonists deter first line use. tctMD. https://www.tctmd.com/news/sky-high-cost-sglt2i-and-glp1-agonists-deter-first-line-use

Medical News Today. (n.d.). Why fad diets don’t work. Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/317546

Montero, A., Sparks, G., Presiado, M., & Hamel, L. (2024, May 10). KFF Health Tracking Poll May 2024: The public’s use and views of GLP-1 drugs. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/poll-finding/kff-health-tracking-poll-may-2024-the-publics-use-and-views-of-glp-1-drugs/

Moorman, J. (2024, July 19). GLP-1 medications and weight loss: Helping patients navigate beyond the trends. Wolters Kluwer. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/expert-insights/glp-1-medications-and-weight-loss-help-patients-navigate-beyond-trends

Morris, M. S. (2024, October 15). Does insurance cover weight-loss medications such as Wegovy or Zepbound?. GoodRx. https://www.goodrx.com/insurance/health-insurance/weight-loss-drugs-covered-by-insurance?srsltid=AfmBOopdpGXsjNNjqX-AiiU6pYk23U6sRDwTBG9mBNnZKaw4OgHDFckw

Morris & Garritano. (2024, April 9). Why is there a shortage of GLP-1 diabetes type 2 medications such as Ozempic?. Morris & Garritano.https://morrisgarritano.com/resource/why-is-there-a-shortage-of-glp-1-diabetes-type-2-medications-such-as-ozempic/

Müller, T. D., Finan, B., Bloom, S. R., D’Alessio, D., Drucker, D. J., Flatt, P. R., Fritsche, A., Gribble, F., Grill, H. J., Habener, J. F., Holst, J. J., Langhans, W., Meier, J. J., Nauck, M. A., Perez-Tilve, D., Pocai, A., Reimann, F., Sandoval, D. A., Schwartz, T. W., Seeley, R. J., … Tschöp, M. H. (2019). Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). Molecular metabolism, 30, 72–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2019.09.010

Muñoz-Garach, A., Cornejo-Pareja, I., & Tinahones, F. J. (2016). Does Metabolically Healthy Obesity Exist?. Nutrients, 8(6), 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8060320

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (2023, May). Health risks of overweight & obesity. In Understanding adult overweight & obesity. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/adult-overweight-obesity/health-risks

Neale, T. (2024, November 13). Many patients quit taking GLP-1 drugs: Understanding why is key. tctMD. https://www.tctmd.com/news/many-patients-quit-taking-glp-1-drugs-understanding-why-key

Nelson, C., & Harris, K. (2018). The dieting dilemma. Utah State University. https://extension.usu.edu/nutrition/research/the-dieting-dilemma

Niewijk, G. (2024, May 30). Research shows GLP‑1 drugs are effective but complex. UChicago Medicine. https://www.uchicagomedicine.org/forefront/research-and-discoveries-articles/research-on-glp-1-drugs

Northwestern Medicine. (2022, December). How your body fights weight loss. HealthBeat: Healthy Tips. https://www.nm.org/healthbeat/healthy-tips/how-your-body-fights-weight-loss nm.org+8nm.org+8nm.org+8

Obesity Medicine Association.(2024). Rising obesity rates in America: A public health crisis. Obesity Medicine Association. https://obesitymedicine.org/blog/rising-obesity-rates-in-america-a-public-health-crisis/

Rissetto, V. (2022, February 7). Why fad diets don’t work. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/why-fad-diets-dont-work globalnews.ca+5healthline.com+5reddit.com+5

Rodgers, E. (2023, September 19). 75+ fast food consumption statistics. DriveResearch. https://www.driveresearch.com/market-research-company-blog/fast-food-consumption-statistics/ b

Rodriguez, P. J., Zhang, V., Gratzl, S., Do, D., Cartwright, B. G., Baker, C., … & Emanuel, E. J. (2025). Discontinuation and Reinitiation of Dual-Labeled GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Among US Adults With Overweight or Obesity. JAMA Network Open, 8(1), e2457349-e2457349.

Sanders, D. M. (2022, June 16). Efficacy of GLP-1 agonists for weight loss in adults without diabetes: Liraglutide and semaglutide. Clinical Advisor. https://www.clinicaladvisor.com/features/glp-1-agonists-weight-loss-adults-without-diabetes-liraglutide-semaglutide/

Schimelpfening, N. (2024, May 6). Trying to form new diet habits? Here’s how long it may take. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health-news/trying-to-form-new-diet-habits-heres-how-long-it-may-take

Seo, H. (2025, April 21). Why GLP-1 weight-loss drugs are hard to make into pills. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-glp-1-weight-loss-drugs-are-hard-to-make-into-pills/

Shields Health Solutions. (2025, April 2). Addressing GLP-1 access and adherence challenges with specialty pharmacy solutions. https://shieldshealthsolutions.com/glp1-access-adherence-specialty-pharmacy/

Sweeney, E. (2024, September 25). Experts explain why you feel hungry after eating. Men’s Health. https://www.menshealth.com/health/a62324563/why-youre-always-hungry-after-eating/#

Temple N. J. (2022). The origins of the obesity epidemic in the USA-lessons for today. Nutrients, 14(20), 4253. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14204253

Thillainadesan, S., Lambert, A., Cooke, K. C., Stöckli, J., Yau, B., Masson, S. W., … & Hocking, S. L. (2024). The metabolic consequences of ‘yo-yo’dieting are markedly influenced by genetic diversity. International Journal of Obesity, 48(8), 1170-1179.

Tin, A. (2025, April 4). Medicare and Medicaid will not cover weight loss drugs, Trump administration decides. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/medicare-and-medicaid-will-not-cover-weight-loss-drugs-trump-administration-decides/

Tirrel, M. (2024, September 17). GLP-1 pills: A new frontier in weight loss treatment. https://www.cnn.com/2024/09/17/health/glp-1-pills-weight-loss-treatment

Tong, N. (2025, January 8). Found introducing oral dissolvable GLP‑1 tablet at reduced price. Fierce Healthcare. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/telehealth/found-introducing-oral-dissolvable-glp-1-tablet

Upton, A., Spirou, D., Craig, M., Saul, N., Winmill, O., Hay, P., & Raman, J. (2025). Health literacy and obesity: A systematic scoping review. Obesity Reviews, e13904.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2025, April 28). FDA clarifies policies for compounders as national GLP‑1 supply begins to stabilize. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-clarifies-policies-compounders-national-glp-1-supply-begins-stabilize

Valloppillil, S. (2025, February 25). The GLP-1 revolution: Everyone and their moms are on GLP-1s. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/sindhyavalloppillil/2025/02/25/the-glp-1-revolution—everyone-and-their-moms-are-on-glp-1s/

Volkow, N. D., Wang, G. J., & Baler, R. D. (2011). Reward, dopamine and the control of food intake: implications for obesity. Trends in cognitive sciences, 15(1), 37-46.

Vytrisalova, M., Touskova, T., Ladova, K., Fuksa, L., Palicka, V., Matoulkova, P., … & Stepan, J. (2015). Adherence to oral bisphosphonates: 30 more minutes in dosing instructions matter. Climacteric, 18(4), 608-616.

Wang, G. J., Volkow, N. D., Logan, J., Pappas, N. R., Wong, C. T., Zhu, W., … & Fowler, J. S. (2001). Brain dopamine and obesity. The lancet, 357(9253), 354-357.

Whitley, H. P., Trujillo, J. M., & Neumiller, J. J. (2023). Special report: potential strategies for addressing GLP-1 and dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist shortages. Clinical Diabetes, 41(3), 467-473.

World Health Organization (2024, March 1). Obesity: Health consequences of being overweight. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/obesity-health-consequences-of-being-overweight#:~:text=Being%20overweight%20or%20obese%20can,endometrial%2C%20breast%20and%20colon).

World Health Organization. (2025, May 7). Obesity and overweight. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

Zolnierek, K. B. H., & DiMatteo, M. R. (2009). Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Medical care, 47(8), 826-834.