The foundational concept behind New Year’s resolutions dates back to ancient times, embedded within spirituality.1 Four thousand years ago, the Babylons made promises to stay on the good side of their gods, and a similar practice continued within ancient Rome.1 In Christianity, the first day of the year became a time for self-reflection and intention setting to continually improve in the future.1

Over time, these practices have evolved beyond religion, but the New Year continues to represent a fresh start during which many individuals making promises to themselves centering around self-improvement or engaging in behavioral change with the expectation of positive outcomes for physical and/or mental health outcomes.1, 2 For instance, some of the most popular and commonly set New Year’s resolutions include weight loss, healthier eating habits, and engaging in physical activity.2 Despite individuals’ best intentions, as time from the first of January increases, the behaviors enacted based on achieving such resolutions diminish.2, 3 A study of 200 New Yorkers found that one week into the New Year 77% of participants had maintained their set resolutions, this decreased to 55% after one month, 43% after three months, 40% after six months.2, 3 At the two year follow up, only 19% of individuals had maintained their resolutions.2, 3 Hence, while setting New Year’s resolutions is easy, executing them over long-term periods can be exceptionally challenging.

Why New Year’s Resolutions Fail: Exploring the Challenges Associated with Long-Term Habit Formation

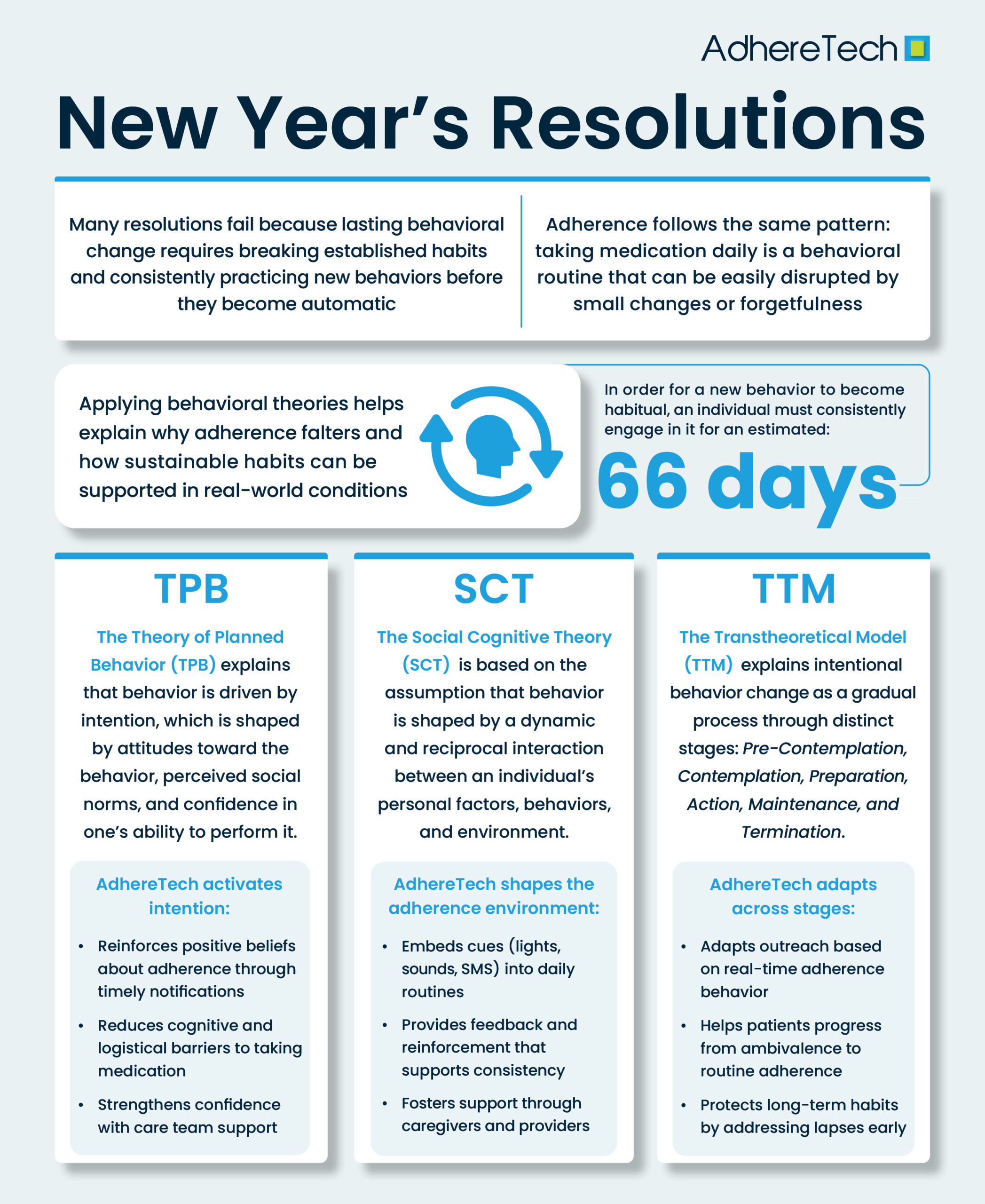

Some of the most common New Year’s resolutions, such as engaging in physical activity, starting new diets, and losing weight, are rooted in behavioral change. However, behavioral change is inherently difficult because it requires individuals to break established habits while simultaneously adopting new behaviors that may feel unfamiliar or require additional effort.2, 4 Human beings are creatures of habit, with daily routines and long-term behaviors often automatic responses to environmental cues.5 Habits are formed through repeated actions in consistent contexts, eventually becoming automatic, resulting in a reduced reliance on conscious decision-making.5 This automaticity enables individuals to conserve cognitive resources for more complex tasks, which subsequently enhances the efficiency of our daily routines.5

Importantly, research suggests that an individual must consistently engage in a new behavior for an estimated 66 days to become habitual.6 This process underscores why many resolutions are likely to fail. Even for motivated individuals, it can be challenging to maintain a new behavior for long enough that it becomes automatic. For example, without proper planning, something as simple as a busy work schedule or sleeping through one’s alarm may result in an individual falling off track with their diet or workout regimen. The same principle applies to medication adherence. Taking medication every day at the same time is, at its core, a behavioral routine.7 When patients begin treatment, or transition to a new regimen, they become increasingly vulnerable to missed doses because the behavior has not become automatic.7 Minor changes in routine or forgetfulness can quickly cascade into unintentional non-adherence, derailing the habit formation process.

Behavioral Insights from New Year’s Resolutions: Supporting Long-Term Medication Adherence

While “cheating” on a diet or failing to follow an intended workout schedule can be disheartening, the consequences of failing to follow one’s medication as prescribed are far more grave. Each year, medication non-adherence causes an estimated 125,000 preventable deaths and 33-69% of medication-related hospital admissions, with indirect and direct healthcare costs totaling over 300 billion in the United States alone.8

As of 2024, every three in four Americans had at least one chronic condition, and over half had two or more.9 Moreover, 66% of adults within the United States have reported using prescription medications, indicating that over half of the adult American population has a prescribed medication regimen they have been prescribed to follow.10 Despite the potential deadly consequences of failing to adhere to one’s medication regimen, research indicates that across chronic conditions, the likelihood of adherence remains the same as a coin toss, an estimated 50%.11

These patterns underscore a large issue for behavioral change: knowing the “right” or “best” behavior is rarely the driving force behind long-term engagement. People can fully understand the importance of exercising, eating well, and taking their medication as instructed, but still struggle to follow through with the behaviors necessary to translate these goals into habits. Information, intention, and even strong motivation may not be enough to translate behavior into a consistent action when inevitable disruptions in daily life occur. To meaningfully improve medication adherence, utilizing behavioral theories to understand why people engage, disengage, and form lasting habits is essential. The following frameworks offer insight into how adherence can be supported within the real world, not just under ideal, theoretical conditions.

Behavioral Change Theories to Explore Medication Non-Adherence

- The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

- TPB proposes that people engage in behavior based on their intention to perform a behavior. It posits that their intention is dependent on their attitudes toward the behavior, perceived social norms, and sense of control over performing the intended behavior.12

- Attitudes → Formed based on their beliefs about the pros and cons of performing a particular behavior,12 such as taking or not taking medication.

- Subjective norms → Refers to a person’s beliefs about what others think about the individual engaging in the intended behavior, in addition to their motivation to abide by the wishes of others.12

- Perceived behavioral control → An individual’s belief that they have the resources and opportunities to perform a particular behavior and overcome potential barriers associated with engaging in the behavior.12

- Ex: A patient may be hesitant to take their medication if they are not experiencing symptoms and do not believe medication is necessary (attitude), feel that others will judge them for taking medication (subjective norms), and believe that they cannot manage a complex dosing schedule (perceived behavioral control).

- TPB proposes that people engage in behavior based on their intention to perform a behavior. It posits that their intention is dependent on their attitudes toward the behavior, perceived social norms, and sense of control over performing the intended behavior.12

- Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)

- SCT is based on the assumption that behavior is shaped by a dynamic and reciprocal interaction between an individual’s personal factors, behaviors, and environment.13

- Personal factors → Refer to things such as beliefs, expectations, and personality.13

- Behavior: The specific actions or conduct performed by the individual.12

- Environmental influences → An individual’s external surroundings, social context, and stimuli (rewards or punishments) in which the intended behavior occurs.13

- Ex: A patient stops taking their medication because they do not perceive immediate benefits (personal), consistently forget to take doses (behavior), and/or feel unsupported by friends and family (environmental). Utilizing SCT, the theory suggests that over time, these factors will reciprocally influence one another:13 missed doses may reinforce doubts about the efficacy of medication, withdrawing from seeking out support to take medication as prescribed will reduce personal motivation, and the person’s environment will lack the necessary cues or reinforcement necessary to promote sustained medication adherence.

- SCT is based on the assumption that behavior is shaped by a dynamic and reciprocal interaction between an individual’s personal factors, behaviors, and environment.13

- The Transtheoretical Model (TTM)

- TTM, also known as the stages of change theory, is a model commonly used in clinical frameworks to outline steps towards change.14 Each stage helps to explain how ready an individual is to engage in behavior change, explaining the process toward behavioral change throughout each stage.14

- Pre-Contemplation: The individual has no intention of taking steps towards behavioral change.14

- Ex: An individual may lack awareness of their condition or the consequences of missing doses, believing that skipping medication occasionally is harmless.

- Contemplation: An individual possesses the intent to take action and intends to do so in the future.14

- Ex: An individual recognizes that missing doses could contribute to declines in their physical or mental health, but they are unsure about how, when, or whether to start taking their medication consistently.

- Preparation: The individual has intentions of taking action and has begun taking steps towards engaging in behavior change.14

- The individual decides they need to start improving their adherence. In this phase, they begin preparing for how to do this, such as by setting reminders, organizing their medication, or speaking with their healthcare provider about a plan.

- Action: The individual has engaged in behavior change for a short duration of time.14

- The individual begins to actively take the steps necessary to adhere to their medication schedule. This may include behaviors such as setting and following medication reminders, tracking doses daily, or utilizing another form of tracking method to facilitate consistent adherence.

- Maintenance: The individual has engaged in behavior change over an extended period of time.14

- The individual consistently takes their medication as prescribed over time, integrating it into their daily routine and addressing minor lapses without abandoning or allowing such slips to derail their regimen.

- Termination: (In theory) The individual has achieved complete self-efficacy in engaging in the changed behavior.14

- Adherence has become fully habitual; the individual no longer struggles with remembering doses, and missing medication is no longer a realistic risk. This stage is defined as “a period with zero temptation for relapse and the achievement of 100% self-efficacy.”14 Even with strong self-efficacy, uncontrollable circumstances can disrupt adherence – travel delays, delays in prescription refills, human forgetfulness, sudden and unprompted changes in routine, or changes in insurance or medication costs.

- Pre-Contemplation: The individual has no intention of taking steps towards behavioral change.14

- TTM, also known as the stages of change theory, is a model commonly used in clinical frameworks to outline steps towards change.14 Each stage helps to explain how ready an individual is to engage in behavior change, explaining the process toward behavioral change throughout each stage.14

While not an explicit theory of behaviorism, research indicates that small, incremental changes are often the most effective method for building durable, long-term habits.5 Gradual changes can help individuals integrate new behaviors into their existing routines, representing small, sustainable changes as opposed to drastic changes that introduce entire variations in routines.5 For instance, smaller dietary adjustments have been associated with greater success in the maintenance of healthy eating habits when compared with crash and/or exceedingly restrictive diets.5 Despite limited research, the same concept is likely to hold when considering medication adherence. Capitalizing on the process commonly referred to as “anchoring,” tying a new behavior into an established routine, such as pairing medication with coffee, teeth brushing, etc., can aid in this gradual shift towards long-term habit formation.5

How AdhereTech Leverages the Principles of Behaviorism to Support Long-Term Medication Adherence

Adherence is a complex behavior influenced by beliefs, environmental cues, social context, and habit strength. AdhereTech’s technology is intentionally designed to leverage the principles of well-established behavioral science frameworks, including the Theory of Planned Behavior, Social Cognitive Theory, and the Transtheoretical Model, to support sustainable improvements in adherence.

Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

TPB emphasizes that medication-taking behavior is driven by intention, shaped by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. AdhereTech’s strategic design allows it to directly strengthen each of these areas:

Attitudes: A patient’s beliefs about the pros and cons associated with performing a particular behavior,12 such as taking or not taking medication.

AdhereTech devices are designed to reduce or eliminate many of the perceived disadvantages that undermine adherence – such as remembering doses, managing complex schedules, or navigating technology. AdhereTech’s ability to provide real-time adherence data to care teams allows for timely, supportive outreach to patients that can reinforce the importance and health impact of following their regimen(s) as prescribed. Furthermore, AdhereTech’s SMS capabilities allow healthcare professionals to enable messaging that can be tailored to remind patients of the importance and health benefits of taking their medication as prescribed. When combined with motivational features – such as encouraging messages that acknowledge adherence “streaks” – these elements work together to positively shift patients’ attitudes and strengthen their belief in the importance and advantage of following their regimen as prescribed.

Subjective Norms: Refers to a person’s beliefs about what others think about the individual engaging in the intended behavior, in addition to their motivation to abide by the wishes of others.12

AdhereTech supports positive subjective norms by offering supportive, nonjudgmental reminders and optional care-team engagement that frame adherence as a shared goal rather than an individual burden. When providers receive real-time alerts and offer empathetic outreach, patients view their adherence as something encouraged and valued by their care team, rather than monitored or criticized. This sense of collaborative support can strengthen the perception that consistent medication-taking is both expected and socially reinforced, increasing a patient’s motivation to adhere to their prescribed regimen. Moreover, the caregiver feature—which allows designated caregivers to receive notifications about their loved one’s medication-taking behaviors, adds a layer of empathetic, relationship-based support, further reinforcing the social encouragement surrounding adherence.

Perceived Behavioral Control: An individual’s belief that they have the resources and opportunities to perform a particular behavior and overcome potential barriers associated with engaging the behavior.12

AdhereTech strengthens perceived behavioral control by reducing the cognitive and logistical burdens that frequently undermine adherence. AdhereTech’s Aidia system simplifies the most challenging aspects of medication-taking, such as remembering doses, managing complex schedules, and troubleshooting device issues, through automatic reminders, real-time connectivity, and passive data capture. In addition, 7-day live support ensures patients can quickly resolve technical questions or connect with their care team promptly, preventing small issues from escalating into missed doses. Collectively, these features increase a patient’s confidence in their ability to manage their regimen successfully, reinforcing the belief that they have both the capability and the support needed to remain adherent over time.

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)13

SCT highlights the reciprocal interaction of personal beliefs, behavior, and environment.13 AdhereTech intentionally modifies each of these domains to break negative behavioral patterns, reinforcing positive ones.

Personal Factors: Refer to things such as beliefs, expectations, and personality.13

AdhereTech strengthens personal factors by directly addressing common uncertainties and barriers that undermine patient’s confidence in their ability to remain adherent. For example, patients may forget whether they have taken a dose or may feel unsure about the importance of their prescribed regimen. Aidia reduces these uncertainties by providing real-time, intuitive reminders that alert patients when a dose is forgotten and can connect patients to their designated care team when doses are missed. This timely guidance helps patients build confidence in their ability to follow their regimen, reinforces the expectation that adherence is both achievable and beneficial, and motivates patients to maintain consistent medication-taking behavior. Over time, these positive personal experiences reinforce the patient’s belief in their own capability and the value of adherence.

Behavior: The specific actions or conduct taken by the individual.13

AdhereTech actively shapes daily medication-taking behavior by delivering reminders via lights, chimes, and SMS messaging, based on individualized dosing schedules that integrate medication into established routines. These external cues reduce reliance on memory alone, supporting patients in establishing a reliable routine without feeling overwhelmed. By consistently prompting action, reinforcing adherence behaviors via motivational messaging, and allowing care teams to track patients’ progress, AdhereTech helps to transform adherence from a sporadic behavior into a stable, automatic behavior. This structured behavioral support encourages patients to take their medication consistently while reinforcing the connection between action and positive health outcomes.

Environment: An individual’s external surroundings, social context, and stimuli (rewards or punishments) in which the behavior occurs.13

AdhereTech creates a supportive environment by sending automated notifications when doses are missed and enabling real-time, empathetic human outreach. This system ensures patients are never navigating adherence challenges alone, providing timely reinforcement and reminders exactly when needed. In addition, optional caregiver notifications allow loved ones to participate in adherence support, creating a broader social network that reinforces adherence. By shaping the environment to consistently support medication-taking, AdhereTech removes external barriers, provides cues and safety nets, and fosters a context in which consistent adherence becomes the default behavior rather than an exception.

Transtheoretical Model (TTM)14

Because patients move through each of the stages outlined by the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) at different paces,14 AdhereTech is structured to meet individuals where they are and support transitions in adherence from early ambivalence to long-term maintenance.

Pre-Contemplation:

In this stage, AdhereTech provides early, empathetic outreach by leveraging real-time adherence data. If a patient misses doses, care teams can intervene in a nonjudgmental way to raise awareness of the importance of consistent medication-taking. These interactions help patients begin reflecting on their adherence patterns and the potential health risks associated with inconsistency, laying the groundwork for later stages of change.

Contemplation:

During contemplation, Aidia’s reminders, feedback, and escalation protocols provide actionable insights that help patients connect their behaviors to meaningful health outcomes. The reminders and feedback help to subconsciously reinforce medication-taking behaviors, while patient care teams can clarify the consequences of missed doses and demonstrate how adherence will positively impact their health. In doing so, AdhereTech reduces uncertainty and strengthens motivation, helping patients consider adopting more consistent medication routines.

Preparation:

In the preparation stage, patients can experiment with reminders, habit-anchoring, and organizational strategies that fit into their daily routines. The AdhereTech device enables patients to develop a structured plan for taking medication consistently without overwhelming their existing, habitual routines with new behaviors. Customizable dosing schedules and reminders allow patients to experiment with developing a reminder system that seamlessly integrates into their existing routines. By enabling small, manageable adjustments, AdhereTech prepares patients for a successful transition to active adherence.

Action:

During the action phase, Aidia supports patients with real-time prompts, habit reminders, and troubleshooting assistance. The system’s automated reminders eliminate the need for patients to track their own adherence behaviors, reducing cognitive load and preventing forgetfulness. Built-in accountability features, such as notifications to care teams when doses are missed, help prevent lapses from escalating and reinforce the behavior as intentional and achievable. This active support ensures that adherence becomes a consistent, repeatable practice rather than an occasional effort.

Maintenance:

AdhereTech helps stabilize these new adherence habits by embedding medication-taking into daily routines, reinforcing small lapses, and ensuring patients receive timely support to avoid forgetting doses. This continuous guidance supports long-term adherence, helping patients maintain behavior change even when daily routines or circumstances fluctuate.

Termination:

Even at this stage, AdhereTech provides safeguards against external disruptions such as travel, schedule changes, or prescription delays. Its global functionality allows patients to adjust dosing times to match their current time zone, while automated reminders ensure that fluctuating schedules do not disrupt adherence. Additionally, the device’s embedded electronic magnetic field can detect when prescriptions are running low and alert both patients and providers to prevent interruptions in medication access. By offering ongoing environmental and behavioral support, AdhereTech helps patients sustain long-term adherence despite unpredictable challenges, ensuring that consistent medication-taking remains a stable, integrated part of their daily routine.

Supporting Gradual, Sustainable Behavior Change

Research shows that lasting habits emerge from incremental changes rather than radical shifts. 5AdhereTech’s approach aligns with this principle by reducing friction, lowering cognitive effort, and embedding medication into existing routines. Through a process similar to “anchoring,”5 patients naturally align medication-taking to familiar daily anchors—coffee, morning hygiene, or bedtime rituals – without needing to reconstruct their entire routine around taking their medication.

By combining behavioral science with thoughtfully designed technology, AdhereTech not only improves immediate adherence but also nurtures the slow, stable repetition of consistent adherence behaviors that translate to habit formation, supporting long-term health.

From Resolutions to Routine: Applying Behavioral Science to Medication Adherence

Just as New Year’s resolutions illustrate, knowing what we should do is rarely enough to support long-lasting behavioral change.2, 4 Setting a resolution to exercise or eat healthier demonstrates intention, but sustaining that behavior requires repeated action, environmental support, and reinforcement until it becomes habitual, occurring subconsciously and automatically.1, 2 Medication adherence operates on the same principles: taking medication consistently is a behavior that must be integrated into daily routines, supported by reminders, social encouragement, and systems that minimize barriers.

Like resolutions, adherence is vulnerable to lapses; missed doses can quickly disrupt habit formation, particularly when routines change or cognitive load is high. However, leveraging insights from behavioral science, such as intention formation, social support, environmental cues, and gradual habit-building, can transform adherence from a well-intentioned but fragile behavior into a stable, self-sustaining routine. By applying these strategies, much like successful approaches to maintaining resolutions, patients can move beyond short-term compliance toward long-term, reliable adherence, ultimately supporting better health outcomes and reducing the personal and societal costs of missed medication.

References

1 Elsig, C. M. (2024, January 10). The psychology behind behaviour change: Why do New Year’s resolutions fail?. Calda Clinic. https://www.caldaclinic.com/news/the-psychology-behind-behaviour-change-why-do-new-years-resolutions-fail/

2 Oscarsson, M., Carlbring, P., Andersson, G., & Rozental, A. (2020). A large-scale experiment on New Year’s resolutions: Approach-oriented goals are more successful than avoidance-oriented goals. PloS one, 15(12), e0234097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234097

3 Norcross, J. C., & Vangarelli, D. J. (1988). The resolution solution: Longitudinal examination of New Year’s change attempts. Journal of substance abuse, 1(2), 127-134.

4 Call, M. (2024, April 15). Why is behavior change so hard?. University of Utah Health. https://healthcare.utah.edu/integrative-health-wellness/resiliency-center/news/2024/04/why-behavior-change-so-hard

5 Akash, M. S., & Chowdhury, S. (2025). Small changes, big impact: A mini review of habit formation and behavioral change principles.

6 Lally, P., van Jaarsveld, C. H. M., Potts, H. W. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(6), 998–1009. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

7 Phillips, L. A., Burns, E., & Leventhal, H. (2021). Time-of-Day Differences in Treatment-Related Habit Strength and Adherence. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 55(3), 280–285. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kaaa042

8 Benjamin R. M. (2012). Medication adherence: helping patients take their medicines as directed. Public health reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974), 127(1), 2–3. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491212700102

9 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, October 4). About chronic diseases. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/chronic-disease/about/index.html

10 Health Policy Institute. (n.d.). Prescription Drugs. Georgetown University. https://hpi.georgetown.edu/rxdrugs/

11 Mathes, T., Pieper, D., Antoine, S. L., & Eikermann, M. (2012). 50% adherence of patients suffering chronic conditions–where is the evidence?. German medical science : GMS e-journal, 10, Doc16. https://doi.org/10.3205/000167

12 Kopelowicz, A., Zarate, R., Wallace, C. J., Liberman, R. P., Lopez, S. R., & Mintz, J. (2015). Using the theory of planned behavior to improve treatment adherence in Mexican Americans with schizophrenia. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 83(5), 985–993. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039346

13 Nickerson, C. (2025, March 31). Albert Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory. SimplyPsychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/social-cognitive-theory.html

14 Raihan, N., & Cogburn, M. (2023, March 6). Stages of Change Theory. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556005/