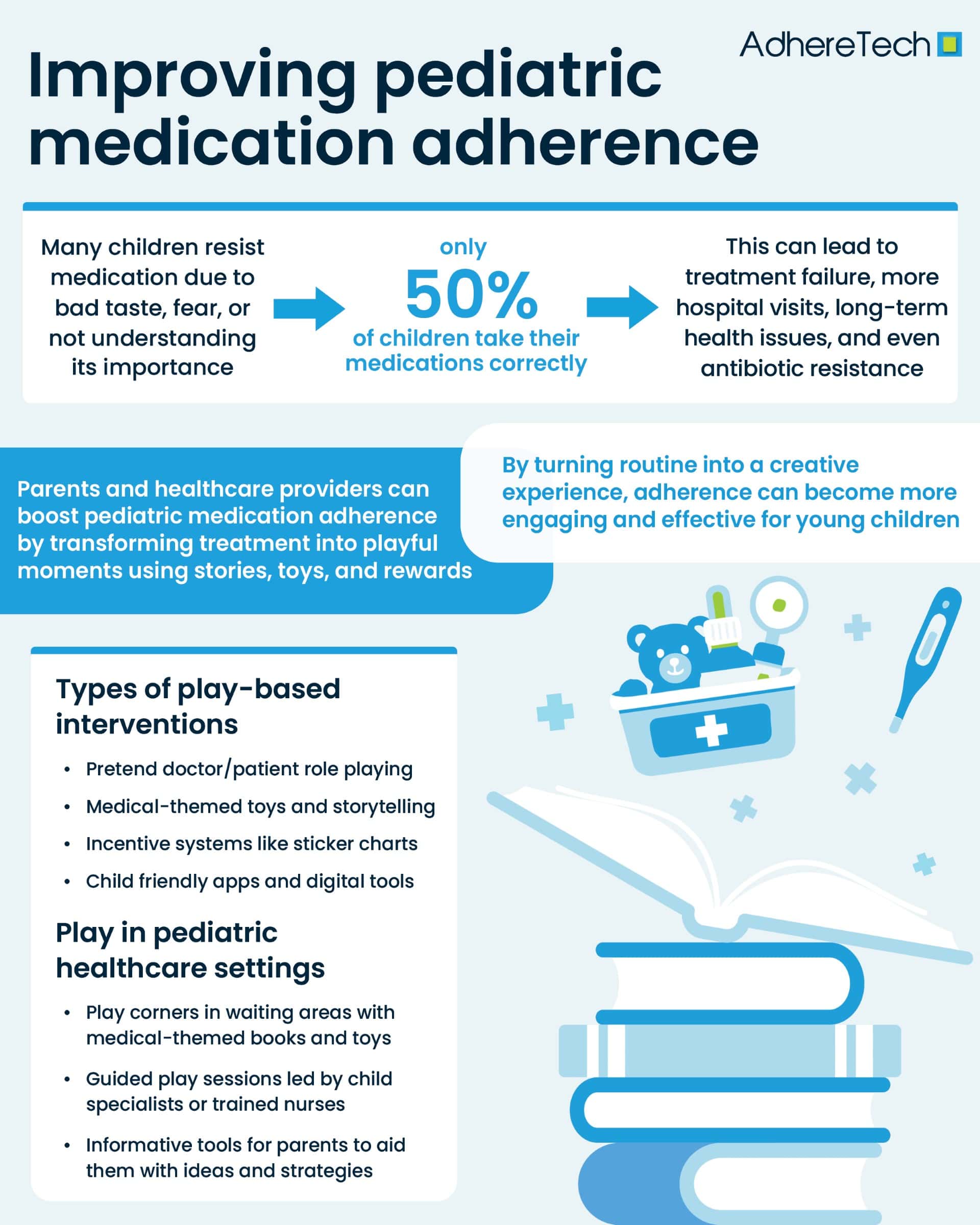

Pediatric medication adherence remains a persistent challenge in healthcare, with many children resisting treatment due to unpleasant tastes, fear, or simply not understanding why the medication is necessary. This resistance can have serious consequences, including treatment failure1, more frequent hospitalizations1, long-term health complications2, and even the development of drug resistance—particularly in the case of antibiotics3. Adherence is especially critical for managing both acute and chronic pediatric conditions, yet research from the World Health Organization indicates that only about 50% of children follow their prescribed medication regimens correctly4.

What Makes Pediatric Adherence Different from Adults?

Unlike adults, children face unique barriers to adherence. They depend heavily on caregivers, may struggle to grasp the importance of taking medicine, and are often more sensitive to the sensory aspects of medications, such as taste and texture5. These factors complicate efforts to maintain consistent treatment, making it vital to find solutions tailored to a child’s developmental stage and emotional needs.

How Play-Based Techniques Can Improve Medication Adherence in Children

One of the most promising and innovative approaches to this issue involves the use of play-based techniques6. Grounded in developmental psychology and educational theory, play-based interventions engage children in age-appropriate, meaningful activities that help them understand, accept, and participate in their treatment7. These techniques can include role-playing, where children act out being doctors or patients; using medical-themed toys like syringes or stethoscopes for imaginative play; storytelling that features characters managing similar health challenges; and incorporating games, sticker charts, or digital apps that gamify the medication process8.

The Psychology Behind Play: Why It Works for Medication Adherence

Play has a profound impact on pediatric adherence by addressing several key psychological and behavioral hurdles9. First, it helps reduce anxiety and fear. Children often associate medication with discomfort or past negative experiences, but through play, they can develop more positive associations10. For example, when a child practices giving a doll its medicine, the real experience becomes less intimidating. In fact, a study published in the Journal of Pediatric Psychology found that therapeutic play significantly reduces procedural anxiety and increases cooperation among young patients11.

Types of Play-Based Interventions for Pediatric Patients

Children respond well to various forms of interactive learning, and play-based interventions can take many creative and engaging forms. One effective approach is role-playing, where children assume roles such as doctors or patients to act out real-life medical scenarios, helping them become more comfortable with treatment routines. Another method involves the use of medical-themed toys—items like stethoscopes, syringes, and pill bottles—allowing children to explore healthcare concepts through pretend play. Storytelling is also powerful; books or personalized stories featuring characters who take medicine can make the experience more relatable and less intimidating. Incorporating games and rewards, such as turning medication schedules into opportunities to earn stickers or small prizes, adds a fun and motivating element. Additionally, digital gamification—using apps and augmented reality tools—can transform medication time into an interactive, game-like experience that keeps children engaged while reinforcing adherence behaviors.

How Parents Can Use Play to Encourage Medication Adherence at Home

At home, caregivers can use a variety of strategies to make medication routines more enjoyable and less stressful for children. One effective approach is to create a medication story—framing the treatment in imaginative terms, such as telling the child that “this syrup helps your white blood cells become superheroes,” which can make the experience more engaging and meaningful. Incorporating toys and props is another helpful method; demonstrating how to take medicine using dolls or action figures allows children to understand the process through play. Establishing a reward system can also boost motivation, with stickers, small tokens, or special privileges offered as positive reinforcement for taking medicine consistently. Finally, involving the child in the routine—by letting them choose the cup, hold the spoon, or help open the container under supervision—gives them a sense of control and participation, making the experience feel more empowering and less intimidating.

Best Practices for Using Play in Pediatric Healthcare Settings

Healthcare providers can also incorporate play-based interventions within clinical environments to support pediatric medication adherence. One effective approach is to create medical play corners in waiting areas, filled with medical-themed books and toys that encourage exploration and familiarity with healthcare concepts. Guided therapeutic play sessions, led by child life specialists or trained nurses, can help children express their feelings and build confidence around medical procedures12. Educating parents is equally important—providing them with practical strategies and toolkits enables them to continue play-based support at home7. In more complex or long-term cases, collaboration with professional play therapists can offer tailored interventions that address deeper emotional or behavioral challenges, ensuring a more comprehensive and child-centered approach to care13.

How Medication Adherence Games Drive Success in Chronic Pediatric Illness

In a case study published in Pediatrics, HopeLab released the Re-Mission video game in 2006 and conducted a randomized controlled trial between 2004 and 2005. The study enrolled 375 adolescents and young adults aged 13 to 29 from 34 medical centers across the United States, Canada, and Australia. Its goal was to assess the effectiveness of Re-Mission in improving treatment adherence, cancer-related knowledge, and self-efficacy among young cancer patients. Results showed that playing Re-Mission significantly increased consistent medication adherence, accelerated gains in cancer knowledge, and boosted patients’ confidence in managing their treatment14.

Medication time doesn’t need to be a source of stress or conflict. By tapping into a child’s natural inclination to play, caregivers and healthcare professionals can transform it into a moment of connection, learning, and healing. As more evidence supports the effectiveness of play-based interventions, it’s becoming clear that play isn’t just about fun—it’s a powerful tool for turning resistance into routine and fear into familiarity. Through stories, games, toys, and technology, we can reshape the future of pediatric medication adherence into something far more engaging, effective, and child-friendly.

References

- Aljofan, Mohamad, et al. “The Rate of Medication Nonadherence and Influencing Factors: A Systematic Review.” Electronic Journal of General Medicine, vol. 20, no. 3, 1 May 2023, p. em471, https://doi.org/10.29333/ejgm/12946.

- Walsh, Caroline A., et al. “The Association between Medication Non‐Adherence and Adverse Health Outcomes in Ageing Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis.” British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, vol. 85, no. 11, 2019, pp. 2464–2478, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6848955/, https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.14075.

- Jimmy, Benna, and Jimmy Jose. “Patient Medication Adherence: Measures in Daily Practice.” Oman Medical Journal, vol. 26, no. 3, May 2021, pp. 155–159, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3191684/, https://doi.org/10.5001/omj.2011.38.

- Mennella, Julie A., et al. “The Bad Taste of Medicines: Overview of Basic Research on Bitter Taste.” Clinical Therapeutics, vol. 35, no. 8, Aug. 2013, pp. 1225–1246, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3772669/, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.06.007.

- El-Rachidi, Sarah, et al. “Pharmacists and Pediatric Medication Adherence: Bridging the Gap.” Hospital Pharmacy, vol. 52, no. 2, Feb. 2017, pp. 124–131, https://doi.org/10.1310/hpj5202-124.

- UNICEF. “Learning through Play: Strengthening Learning through Play in Early Childhood Education Programmes.” UNICEF, 2018.

- “Play in Hospital – Alder Hey Children’s Hospital Trust.” Alder Hey Children’s Hospital Trust, 16 Oct. 2024, www.alderhey.nhs.uk/conditions/patient-information-leaflets/play-in-hospital/.

- Nijhof, Sanne L., et al. “Healthy Play, Better Coping: The Importance of Play for the Development of Children in Health and Disease.” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, vol. 95, no. 95, Dec. 2018, pp. 421–429, www.cs.uu.nl/groups/MG/multimedia/publications/art/healthyplay%20neubiorev2018.pdf, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.09.024.

- Li, Ho Cheung William, and Violeta Lopez. “Effectiveness and Appropriateness of Therapeutic Play Intervention in Preparing Children for Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial Study.” Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, vol. 13, no. 2, Apr. 2008, pp. 63–73, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6155.2008.00138.x.

- Godino-Iáñez, María José, et al. “Play Therapy as an Intervention in Hospitalized Children: A Systematic Review.” Healthcare, vol. 8, no. 3, 29 July 2020, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7551498/, https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030239.

- British Association of Play Therapists. “What Is Play Therapy? – the British Association of Play Therapists.” British Association of Play Therapists, 31 May 2023, www.bapt.info/play-therapy/what-is-play-therapy/.

- Beale, Ivan L., et al. “Improvement in Cancer-Related Knowledge Following Use of a Psychoeducational Video Game for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer.” Journal of Adolescent Health, vol. 41, no. 3, Sept. 2007, pp. 263–270, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.04.006.