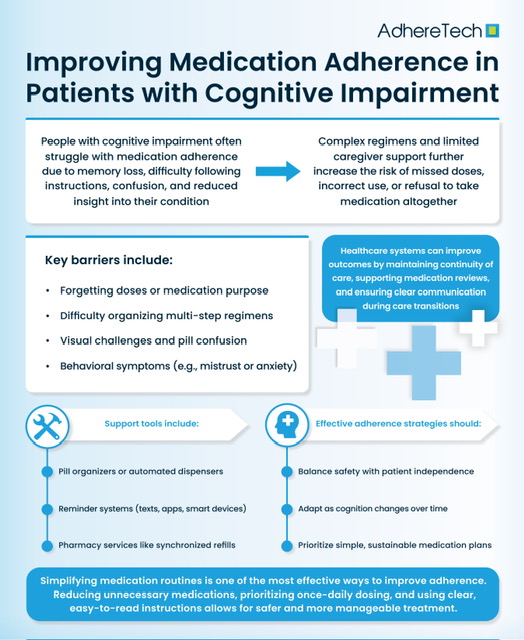

Medication adherence is a cornerstone of effective healthcare.1 For individuals with cognitive impairment, however, taking medications correctly and consistently can be a daily challenge.2 Memory loss, reduced executive function, confusion about instructions, and decreased insight into illness all contribute to missed doses, incorrect timing, or accidental overuse.2 These challenges place patients at higher risk for worsening symptoms, avoidable hospitalizations, and reduced quality of life.2 Improving medication adherence in this population requires a thoughtful, compassionate, and an approach that addresses both clinical and human factors.

Understanding the Barriers

Cognitive impairment spans a wide range of conditions, including mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer disease, vascular dementia, Parkinson related cognitive decline, and brain injury.3 Each condition affects medication adherence in different ways, but common barriers are easy to identify.

Memory deficits are often the most obvious obstacle. Patients may forget whether they have taken a medication, forget scheduled dosing times, or forget the purpose of the medication entirely.4 Executive dysfunction adds another layer of difficulty.4 Planning, sequencing tasks, and problem solving are required to manage even simple medication regimens.4 Visual and spatial impairments can make it hard to read labels or distinguish pills.4 In later stages, patients may develop mistrust or fear, leading to intentional refusal of medications.3,4

Complex medication regimens also contribute to poor adherence.5 Multiple daily doses, similar looking pills, frequent changes, and unclear instructions overwhelm patients who already struggle with cognition.5 Finally, social factors such as living alone, limited caregiver support, or financial constraints further complicate adherence.6

Simplifying the Medication Regimen

One of the most effective strategies for improving adherence is simplifying the medication regimen whenever possible.5 Clinicians should regularly review all prescribed and over the counter medications to identify opportunities for deprescribing. Reducing unnecessary medications not only improves adherence but also lowers the risk of adverse drug events, which can further impair cognition.5

When medications are necessary, once daily dosing should be prioritized. Extended release formulations can be helpful if clinically appropriate.6 Aligning medication schedules with daily routines such as meals or bedtime can also improve consistency.7 Clear, concise instructions using plain language are essential, and written instructions should be easy to read with large fonts and minimal medical jargon.8

Using Medication Aids and Technology

Medication aids are powerful tools for supporting patients with cognitive impairment. Simple pill organizers with daily or weekly compartments can significantly reduce missed doses when used correctly.9 For patients with more advanced impairment, locked or automated pill dispensers can provide medications at scheduled times while preventing double dosing.9

Technology also offers additional support. Electronic reminders through smartphone apps, smart speakers, or text messages can prompt patients or caregivers when it is time to take medications.10 Some devices also track adherence and alert caregivers if a dose is missed.10 While not all patients are comfortable with technology, even basic reminder systems can be highly effective when matched to the individual’s abilities.

Engaging Caregivers and Family Members

Caregivers play a critical role in medication adherence for patients with cognitive impairment.11 Family members, friends, or professional caregivers often serve as medication managers, especially as impairment progresses.11 Their involvement should be encouraged early, before adherence problems become severe.

Education is key. Caregivers need clear explanations of each medication’s purpose, dosing schedule, and potential side effects.12 Written medication lists should be kept up to date and shared across healthcare settings. Encouraging caregivers to observe medication administration can help identify barriers such as difficulty swallowing pills or confusion about timing.12

It is also important to recognize caregiver burden. Managing medications can be stressful and time consuming. Offering support, resources, and respite can improve caregiver well being and indirectly enhance adherence for the patient.13

Creating Supportive Healthcare Systems

Healthcare systems can do more to support medication adherence in cognitively impaired patients. Continuity of care is especially important.14 Frequent changes in providers or pharmacies increase the risk of medication errors and confusion.14 Whenever possible, patients should use a single pharmacy that can provide medication synchronization and packaging services.14

Pharmacists are valuable partners in adherence efforts. They can conduct medication reviews, identify drug interactions, recommend simplification strategies, and provide adherence packaging such as blister packs.15 Regular follow up appointments allow clinicians to reassess adherence, monitor for side effects, and adjust regimens as cognitive function changes.15

Clear communication across care settings is essential. Hospitalizations and transitions of care are high risk periods for medication errors.16 Discharge instructions should be reviewed with both patients and caregivers, and follow up calls can help ensure medications are being taken correctly at home.16

Addressing Behavioral and Psychological Factors

Medication refusal or inconsistent use is not always due to forgetfulness. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of cognitive impairment such as anxiety, depression, paranoia, or agitation can interfere with adherence.17 Addressing these symptoms may improve cooperation with medication routines.

A calm, respectful approach to medication administration is crucial.18 Arguing or forcing medications can damage trust and increase resistance. Instead, offering choices, explaining the purpose in simple terms, and maintaining a consistent routine can reduce distress.18 In some cases, switching formulations such as using liquids or crushing pills when safe may improve acceptance.18

Ethical Considerations and Autonomy

Balancing safety with autonomy is a delicate issue in patients with cognitive impairment. Early in the disease course, patients should be involved in decisions about medication management and future planning.19 Advance discussions about when caregiver oversight may become necessary can ease transitions later.19

As impairment progresses, surrogate decision makers may need to take a more active role. The goal should always be to respect the patient’s values and preferences while ensuring their safety and well being.20 Regular reassessment of capacity and adherence helps guide these decisions.20

Measuring Success and Adapting Over Time

Improving medication adherence is not a one time intervention. Cognitive impairment is often progressive, and strategies that work today may be insufficient tomorrow. Ongoing monitoring is essential. Signs of poor adherence include unexplained symptom worsening, frequent refill delays, or discrepancies between reported and actual medication use.

Success should be measured not only by adherence rates but also by patient outcomes and quality of life. A simpler regimen that is consistently followed may be more beneficial than a complex ideal plan that is rarely executed. Flexibility and willingness to adapt are key.

References

Alzheimer’s Society. “Taking Dementia Medications | Alzheimer’s Society.” Www.alzheimers.org.uk, 2024, www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/treatments/dementia-medication/taking-dementia-medications.

Arlt, Sönke, et al. “Adherence to Medication in Patients with Dementia.” Drugs & Aging, vol. 25, no. 12, 2008, pp. 1033–1047, link.springer.com/article/10.2165%2F0002512-200825120-00005, https://doi.org/10.2165/0002512-200825120-00005.

Burnier, Michel. “Medication Adherence and Persistence as the Cornerstone of Effective Antihypertensive Therapy.” American Journal of Hypertension, vol. 19, no. 11, 1 Nov. 2006, pp. 1190–1196, academic.oup.com/ajh/article/19/11/1190/178087, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.04.006.

Chippa, Venu, and Kamalika Roy. “Geriatric Cognitive Decline and Polypharmacy.” PubMed, StatPearls Publishing, 2023, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574575/.

Cloak, Nancy, et al. “Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms in Dementia (BPSD).” PubMed, StatPearls Publishing, 27 Feb. 2024, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551552/.

Clough, Alexander J, et al. “Medication Management Information Priorities of People Living with Dementia and Their Carers: A Scoping Review.” Age and Ageing, vol. 53, no. 9, 1 Sept. 2024, academic.oup.com/ageing/article/53/9/afae200/7758863, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afae200.

Corrigan, Patrick W., et al. “The Rational Patient and Beyond: Implications for Treatment Adherence in People with Psychiatric Disabilities.” Rehabilitation Psychology, vol. 59, no. 1, 2014, pp. 85–98, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034935.

Elliott, Rohan A, et al. “Ability of Older People with Dementia or Cognitive Impairment to Manage Medicine Regimens: A Narrative Review.” Current Clinical Pharmacology, vol. 10, no. 3, 2015, pp. 213–21, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26265487, https://doi.org/10.2174/1574884710666150812141525.

Klinedinst, Tara C., et al. “The Roles of Busyness and Daily Routine in Medication Management Behaviors among Older Adults.” Journal of Applied Gerontology, vol. 41, no. 12, 11 Aug. 2022, p. 073346482211202, https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648221120246.

Laven, Anna. “How Pharmacists Can Encourage Patient Adherence to Medicines.” The Pharmaceutical Journal, 1 Aug. 2018, pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/how-pharmacists-can-encourage-patient-adherence-to-medicines.

Marnfeldt, Kelly, and Kate Wilber. “The Safety-Autonomy Grid: A Flexible Framework for Navigating Protection and Independence for Older Adults.” The Gerontologist, vol. 65, no. 6, 17 Mar. 2025, academic.oup.com/gerontologist/advance-article/doi/10.1093/geront/gnaf111/8082030, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaf111.

Mone, Pasquale, et al. “Extended-Release Metformin Improves Cognitive Impairment in Frail Older Women with Hypertension and Diabetes: Preliminary Results from the LEOPARDESS Study.” Cardiovascular Diabetology, vol. 22, no. 1, 21 Apr. 2023, p. 94, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37085892/, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-01817-4. Accessed 27 June 2024.

Montine, Thomas J., et al. “Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults and Therapeutic Strategies.” Pharmacological Reviews, vol. 73, no. 1, 9 Dec. 2020, pp. 152–162, https://doi.org/10.1124/pharmrev.120.000031.

Muñoz-Contreras, María Cristina, et al. “Role of Caregivers on Medication Adherence Management in Polymedicated Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease or Other Types of Dementia.” Frontiers in Public Health, vol. 10, 24 Oct. 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.987936.

O’Conor, Rachel, et al. “Managing Medications among Individuals with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: Patient‐Caregiver Perspectives.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, vol. 72, no. 10, 15 July 2024, https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.19065.

“People Affected by Dementia Try out a Smart Reminder Device.” Alzheimer’s Society, 2025, www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-support/publications-and-factsheets/dementia-together/people-dementia-try-smart-reminder-device.

Polenick, Courtney A, et al. “Stressors and Resources Related to Medication Management: Associations with Spousal Caregivers’ Role Overload.” The Gerontologist, vol. 60, no. 1, 24 Oct. 2018, pp. 165–173, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny130.

Sherman, Deborah Witt, et al. “A Systematic Review of the Relationship between Social Isolation and Physical Health in Adults.” Healthcare, vol. 12, no. 11, 1 Jan. 2024, p. 1135, https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111135.

Varghese, Shawn, et al. “Medication Supports at Transitions between Hospital and Other Care Settings: A Rapid Scoping Review.” Patient Preference and Adherence, vol. Volume 16, Feb. 2022, pp. 515–560, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8887864/, https://doi.org/10.2147/ppa.s348152.

Wilkins, James M. “Reconsidering Gold Standards for Surrogate Decision Making for People with Dementia.” Psychiatric Clinics of North America, vol. 44, no. 4, Dec. 2021, pp. 641–647, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2021.08.002.