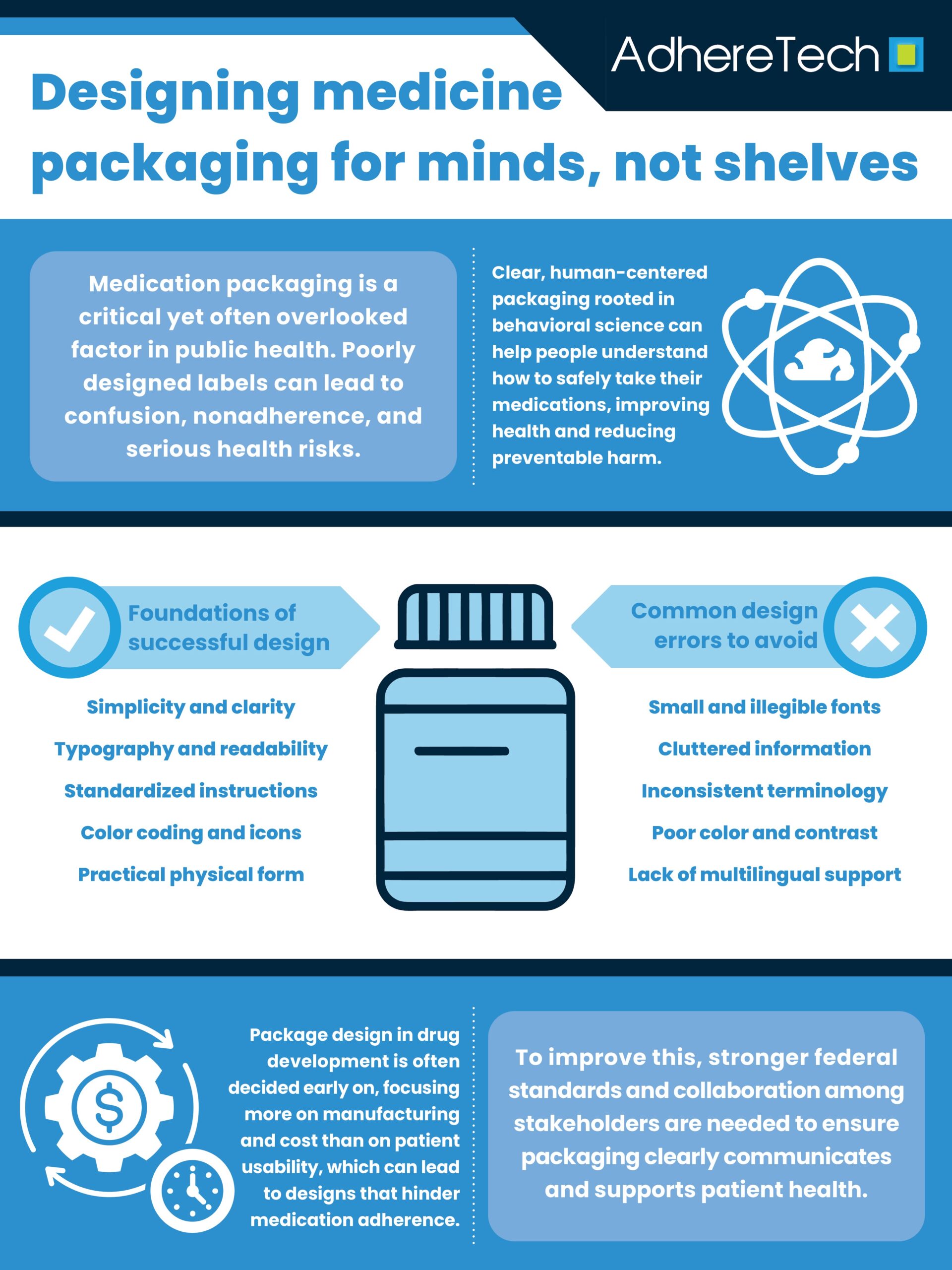

Medication packaging plays a crucial role in public health.1 Beyond protecting the product, good packaging guides safe and effective use.1 However, for many patients, especially those with limited health literacy1 (which is defined as the extent to which people can locate, comprehend, and apply information and services to make informed health decisions and take appropriate actions for themselves and those around them2). Medication labels can be confusing, unclear, or even misleading. Poorly designed packaging contributes to medication errors, unintentional nonadherence, and preventable hospitalizations.3

Thoughtful design—rooted in behavioral science, accessibility, and human-centered principles—can improve the usability of medication packaging and labels for a diverse population.4

Why Packaging Design Matters

Consider a patient with multiple prescriptions. They open their cabinet to find numerous bottles, all of which have small fonts, unclear abbreviations, and inconsistent instructions. One label says “Take twice daily”; another says “Take every 12 hours.” Does this mean they can consume these doses at the same time? Does twice daily mean they must be taken 12 hours apart?

When they pick up a new round of their prescription, the pills are blue and circular as opposed to oval-shaped and white, is this the same medication? Is this a different dose? Is it safe to take?

Confusion like this isn’t rare. According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM), 90 million Americans have limited health literacy.5 Even patients with high levels of health literacy can struggle when medical instructions are vague, poorly formatted, or buried in complex tiny text on the dosing and informational manual provided.6

The World Health Organization estimates that poor adherence to medications causes up to 50% of treatment failures and thousands of deaths annually.7 Packaging can be a powerful tool to reverse that trend.

Recommendations for “Good” Packaging Design:

- Comprehension: The ability for patients to understand the meaning and implications of medication instructions and packaging

- Using simple language, making directions clear and consistent

- Accessibility: Affording all patients the opportunity to acquire the same information.

- Supporting users with visual or cognitive impairments

- Simple language (easily understood)

- Providing necessary translation services

- Safety: Ensuring all patients understand prescribed instructions, are aware of potential interactions, and maintain accurate medication lists to prevent drug interactions.

- Preventing dosing errors and mix-ups

- Warning to patients about dangers of not taking or taking too much medication

- Adherence: Degree to which patient behavior corresponds with agreed upon recommendations from healthcare providers, including timing, dosing, and frequency.

- Devices that help people stick to regimens

- Clear, consistent instructions that clearly outline dosing, timing, and frequency.

The Problems with Current Packaging

Despite regulations, current medication packaging often fall short of these recommendations. Common issues include:

1. Small and Illegible Fonts

Text size is often too small for older adults or patients with visual impairments. Critical information—like dosage, expiration dates, or warnings—can be nearly impossible to read.8

2. Cluttered Information

Labels often contain excess medical jargon, legal disclaimers, and unnecessary repetition. This overwhelms users and distracts from information obtaining vital instructions.9

3. Inconsistent Terminology

Phrases like “Take once a day,” “Take every 24 hours,” and “Daily” may appear interchangeable but can confuse patients—especially when multiple meds are involved using different terminologies.

4. Poor Color and Contrast

Low-contrast text, lack of color-coding, or similar-looking packaging can lead to dangerous mix-ups.2

5. Lack of Multilingual Support

For non-English speakers, lack of translated instructions or symbols reduces comprehension and increases risk.10 Many will use translation tools (such as Google translate), which can give inaccurate translations, and cause incorrect use of medication

Principles of Better Packaging Design

1. Simplicity and Clarity

Good design begins with clarity. Instructions should be written at a 5th to 6th-grade reading level, avoiding abbreviations like “PO” (by mouth) or “BID” (twice a day). Using plain language—such as “Take 1 pill in the morning and 1 pill at night”—is more universally understood.

Visual hierarchy is also important. The most important information (e.g., drug name, dosage, timing) should be prominent, while less critical details (e.g., manufacturer address) can be minimized.

2. Typography and Readability

The U.S. Pharmacopeia recommends using at least 12-point font in sans-serif typefaces like Arial or Helvetica.11 High-contrast colors (black text on white background) further improve legibility.

3. Standardized Instructions

Using standardized language helps patients understand and compare medications easily. Research from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) supports standardizing phrasing to reduce dosing errors.12 For example: “Take 1 pill in the morning and 1 pill at night” is clearer than “Take twice daily”. “Take with food” is better than “PC” (post cibum).

4. Color Coding and Icons

Color coding can reduce confusion, especially for patients with multiple prescriptions. Assigning a consistent color to each medication (as can be done with the AdhereTech medication bottles)—along with a unique icon or pictogram—helps distinguish drugs at a glance.2 However, designers must be cautious. Color-blind users may struggle to differentiate certain hues, and the use of patterns or shapes alongside colors may mitigate against this.

Pictograms, such as a sun for morning or a bed for nighttime use, help overcome language barriers and support patients with low literacy. Studies show that combining pictograms with text reduces dosing mistakes and improves recall.13

5. Packaging Form Factor

The physical design of packaging matters too. For instance:

- Blister packs can help patients track doses, especially when labeled with days of the week14

- Easy-open containers benefit older adults or those with limited dexterity15

- Child-resistant closures must balance safety with ease of access for those with arthritis or disabilities15

- Innovative packaging, such as smart pill bottles or reminder-enabled packs, can further support adherence16 and ensure accurate dosing

An example of well designed and thoughtful medication packaging can be found in the U.S. Veterans Health Administration (VHA). The VHA implemented standardized labels across its pharmacies, including bolded drug names, larger fonts, and consistent instructions. Evaluations showed improved patient understanding and satisfaction.17

Inclusive Design for a Diverse Population

Designing for health means designing for everyone—regardless of literacy, language, vision, or cognitive ability. That includes:

- Multilingual instructions or pictograms for non-English speakers

- Braille or audio-enabled labels for blind or low-vision patients

- Easy-to-follow visuals for people with cognitive disabilities or dementia

By testing packaging with real patients across diverse populations, manufacturers can identify problems early and ensure usability extends across all potential patients.

The Design Process

In the drug development process, packaging design is typically addressed at a surprisingly early stage—often well before a full understanding of the disease state, patient population, or real-world use patterns is established.18 At this point, decisions are frequently driven more by manufacturing efficiency, regulatory compliance, and cost-containment than by usability or patient comprehension.19 As a result, critical aspects of packaging (such as clarity of instructions, ease of access, or adaptability to patient needs) can be overlooked or undervalued.20 This early lock-in limits flexibility later in the process, when insights from clinical trials or human factors testing might otherwise inform more patient-centered design choices. Thus, the prioritization of logistical and economic factors during initial development can unintentionally create packaging that hinders rather than helps medication adherence and effective use.

Policy and Regulation

In 2006, the U.S. Pharmacopeia issued voluntary guidance on medication label design.21 Yet adoption remains uneven. Advocates call for updated federal standards requiring22:

- Minimum font sizes and contrast levels

- Plain language instructions

- Testing with real users before approval

Medication packaging is more than a container. It’s a communication tool that can save lives. When designed well, it empowers patients to take control of their health. When designed poorly, it introduces risk and confusion.

Pharmaceutical companies, designers, regulators, and healthcare providers must collaborate to prioritize patient-centered packaging. The tools and research already exist. What’s needed now is the will to use them.

References

- Aceves-Gonzalez, Carlos, et al. “Estimating the Impact of Label Design on Reducing the Risk of Medication Errors by Applying HEART in Drug Administration.” European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, vol. 80, no. 4, 29 Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-024-03619-3.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “What Is Health Literacy?” Health Literacy, 16 Oct. 2024, www.cdc.gov/health-literacy/php/about/index.html.

- Archroma Packaging Technologies. “Designing Pharma Packaging for Child Safety and Ease of Use by Seniors.” Packaging Europe, 2021, packagingeurope.com/designing-pharma-packaging-for-child-safety-and-ease-of-use-by-seniors/9913.article. Accessed 18 July 2025.

- Bix, Laura, et al. “Is the Test of Senior Friendly/Child Resistant Packaging Ethical?” Health Expectations : An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, vol. 12, no. 4, 1 Dec. 2009, pp. 430–437, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5060504/, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00534.x. Accessed 24 Nov. 2020.

- ECA Academy. “FDA´S New Guidance on Readability.” Gmp-Compliance.org, ECA Academy, 30 June 2022, www.gmp-compliance.org/gmp-news/fdas-new-guidance-on-readability?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Accessed 18 July 2025.

- Endestad, Tor, et al. “Package Design Affects Accuracy Recognition for Medications.” Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, vol. 58, no. 8, 27 Sept. 2016, pp. 1206–1216, https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720816664824.

- Grauer, Anne, et al. “Examining Medication Ordering Errors Using AHRQ Network of Patient Safety Databases.” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, vol. 30, no. 5, 30 Jan. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocad007.

- Guidance for Industry Best Practices in Developing Proprietary Names for Drugs DRAFT GUIDANCE Drug Safety. 2014.

- Gursul, Deniz. “Health Literacy: How Can We Improve Health Information?” NIHR Evidence, 13 June 2022, evidence.nihr.ac.uk/collection/health-information-are-you-getting-your-message-across/.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Literacy, et al. “Executive Summary.” Nih.gov, National Academies Press (US), 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK216029/.

- Leat, Susan J., et al. “Improving the Legibility of Prescription Medication Labels for Older Adults and Adults with Visual Impairment.” Canadian Pharmacists Journal : CPJ, vol. 149, no. 3, 1 May 2016, pp. 174–184, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4860753/, https://doi.org/10.1177/1715163516641432.

- Liu, Kelly, and John F. ODonovan. “Pharmacy Packaging and Inserts.” PubMed, StatPearls Publishing, 2022, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559201/.

- Pandey, Mamata, et al. “Impacts of English Language Proficiency on Healthcare Access, Use, and Outcomes among Immigrants: A Qualitative Study.” BMC Health Services Research, vol. 21, no. 1, 26 July 2021, pp. 1–13, bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-021-06750-4, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06750-4.

- Park, Hyang Rang, et al. “Effect of a Smart Pill Bottle Reminder Intervention on Medication Adherence, Self-Efficacy, and Depression in Breast Cancer Survivors.” Cancer Nursing, vol. Publish Ahead of Print, 12 Oct. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1097/ncc.0000000000001030.

- Saleem, Ahsan, et al. “Investigating the Impact of Patient-Centred Labels on Comprehension of Medication Dosing: A Randomised Controlled Trial.” BMJ Open, vol. 11, no. 11, Nov. 2021, p. e053969, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053969.

- Trokic, Hana. “Medicine Packaging: Navigating Regulations in the UK.” Globalvision.co, GlobalVision, 17 July 2024, www.globalvision.co/blog/medicine-packaging-navigating-regulations-in-the-uk. Accessed 18 July 2025.

- World health Organisation. “Failure to Take Prescribed Medicine for Chronic Diseases Is a Massive, World-Wide Problem.” Www.who.int, 1 July 2003, www.who.int/news/item/01-07-2003-failure-to-take-prescribed-medicine-for-chronic-diseases-is-a-massive-world-wide-problem.

- Algorri, Marquerita, et al. “Patient-Centric Product Development: A Summary of Select Regulatory CMC and Device Considerations.” Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, vol. 112, no. 4, Feb. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xphs.2023.01.029.

- Food and Drug Administration. “The Drug Development Process.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 4 Jan. 2018, www.fda.gov/patients/learn-about-drug-and-device-approvals/drug-development-process.

- Rigby, M. “Pharmaceutical Packaging Can Induce Confusion.” BMJ, vol. 324, no. 7338, 16 Mar. 2002, pp. 679a679, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7338.679/a. Accessed 23 Mar. 2020.

- Yin, H. Shonna, et al. “Pictograms, Units and Dosing Tools, and Parent Medication Errors: A Randomized Study.” Pediatrics, vol. 140, no. 1, 27 June 2017, p. e20163237, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3237.

- Young, Jay. “Why Are Pharmaceutical Labels Important and What Happens If Products Are Labelled Incorrectly?” Uk.com, Premier Labels, 15 Sept. 2022, www.premierlabels.uk.com/news/why-are-pharmaceutical-labels-important-and-what-happens-if-products-are-labelled-incorrectly.