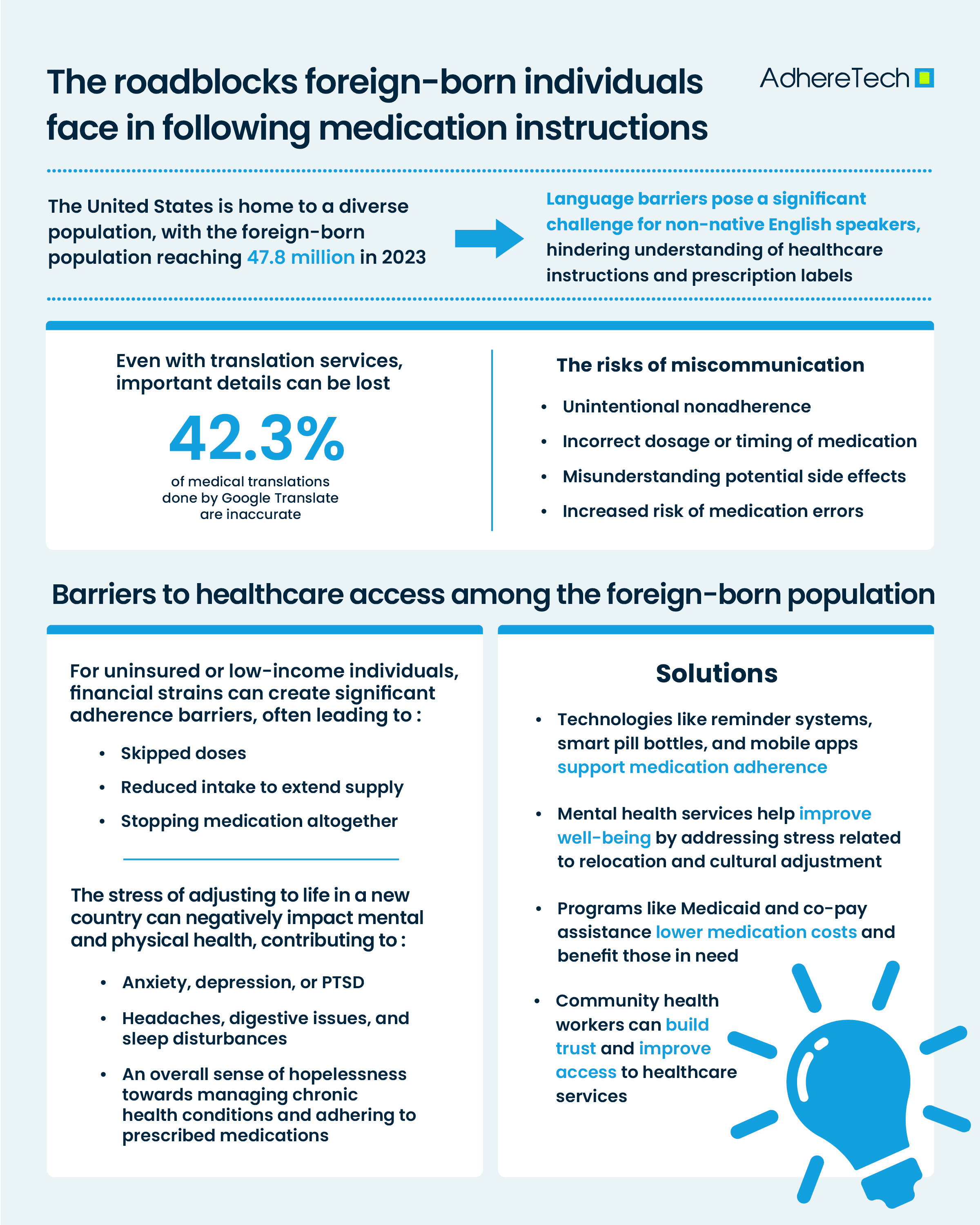

The United States is home to a diverse population, with the foreign-born population reaching 47.8 million in 20231. For many immigrants, navigating the healthcare system is an overwhelming task, with a series of barriers that make it challenging for them to adhere to their prescribed medications2. While healthcare access has improved in recent years, several unique challenges still hinder immigrant populations from following medication regimens effectively.

Language Barriers in Healthcare and Immigrant Adherence

One of the most significant hurdles faced by the foreign-born population are language barriers3. When individuals are unable to fully understand their healthcare provider’s instructions or the details outlined on prescription labels, it becomes exceedingly difficult to follow prescribed treatment plans3. Even with translation services or bilingual providers, nuanced medical instructions can still be lost in translation—with google translate only having a 57.7% accuracy rating when used for medical translations4. Misunderstanding how to properly take medications, including dosage, timing, and potential side effects, can result in unintentional non-compliance, medication errors, or even harm to the patient’s health5. To mitigate this, healthcare providers should aim to provide translated prescriptions, educational materials, and bilingual healthcare professionals—all of which can help alleviate language barriers.

Medication Non-adherence Issues With Refugee And Immigrant Patients

Those without permanent residency or health insurance, often struggle with the financial burden of healthcare6. Furthermore, those with limited access to affordable healthcare may be forced to choose between paying for medications or addressing other essential needs like food, housing, or education7. This financial strain frequently results in patients intentionally skipping doses, reducing the number of pills taken, or even stopping their medication altogether7. Moreover, for those without insurance or a stable income, the co-pays or out-of-pocket expenses associated with their prescriptions may be extensive, preventing them from acquiring their medication, further preventing adherence6. There are numerous existing programs that aim to help subsidize or reduce the cost of medications for low-income or uninsured individuals (For example Medicaid, Medicare Savings Programs, and Federally Qualified Health Centers and co-pay programs developed by pharmaceutical companies, which aim to reduce the out of pocket that patients have to pay for their medicines), which should be brought to the attention of those in need to ease the financial burden of healthcare.

Immigrants of low socioeconomic and/or undocumented status may have limited access to healthcare services8. Without routine check-ups, they may not receive appropriate prescriptions, and any necessary follow-up visits for ongoing medication management may be infrequent or nonexistent. Some immigrants may also fear seeking medical help due to concerns about their immigration status, a lack of familiarity with the healthcare system, or concerns over discrimination8. As a result, they may be more likely to self-medicate, use over-the-counter remedies, or even go without treatment, exacerbating health problems in the long-term9. Training and deploying community health workers from who understand the needs and barriers of undocumented individuals can improve trust and access to healthcare services.

Depression Among Immigrants

The stress associated with immigration itself can also significantly impact medication adherence10. Immigrants often face a series of challenges, such as adjusting to a new culture, navigating unfamiliar bureaucratic systems, and coping with the pressures of supporting family members back home or sending remittances2. This ongoing stress can take a toll on their mental and physical health, leading to conditions such as anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)7. Physical manifestations of stress experienced during the immigration process is also common, with headaches, digestive issues, sleep disturbances, and muscle pain all being common symptoms reported11. These factors can contribute to an overall sense of hopelessness or neglect when it comes to managing chronic health conditions and adhering to prescribed medications10. The use of mental health services that address the stress and trauma associated with immigration can also play a significant role in improving overall well-being, which is closely linked to better medication adherence.

Medication adherence devices such as reminder systems, smart pill bottles, and mobile applications can greatly support immigrant patients by addressing specific barriers they may encounter. The inclusion of multilingual interfaces, secure and confidential data management, and integration with community health resources can help immigrant populations overcome the unique set of challenges they face in adhering to prescribed medications. Addressing these challenges requires an approach that combines cultural sensitivity, financial assistance, improved healthcare access, and targeted support from both healthcare providers and the broader community. By recognizing these barriers and taking concrete steps to support immigrant patients, we can ensure better health outcomes for this vulnerable population.

References

- Moslimani, Mohamad, and Jeffrey S. Passel. “What the Data Says about Immigrants in the U.S.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 27 Sept. 2024, www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/09/27/key-findings-about-us-immigrants/.

- Ahmer Raza, Muhammad, et al. “Addressing Quality Medication Use among Migrant Patients: Establishment of an Organization to Provide Culturally Competent Medication Care.” Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal, 13 Dec. 2023, p. 101922, linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1319016423004176, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2023.101922.

- Kahler, Luke, and Joseph LeMaster. “Understanding Medication Adherence in Patients with Limited English Proficiency.” Kansas Journal of Medicine, vol. 15, no. 1, 11 Jan. 2022, pp. 345–350, https://doi.org/10.17161/kjm.vol15.15912.

- Patil, S., and P. Davies. “Use of Google Translate in Medical Communication: Evaluation of Accuracy.” BMJ, vol. 349, 15 Dec. 2014, pp. g7392–g7392, www.bmj.com/content/349/bmj.g7392.full, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7392.

- Jimmy, Benna, and Jimmy Jose. “Patient Medication Adherence: Measures in Daily Practice.” Oman Medical Journal, vol. 26, no. 3, May 2021, pp. 155–159, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3191684/, https://doi.org/10.5001/omj.2011.38.

- Rohatgi, Karthik W., et al. “Medication Adherence and Characteristics of Patients Who Spend Less on Basic Needs to Afford Medications.” The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, vol. 34, no. 3, 1 May 2021, pp. 561–570, www.jabfm.org/content/34/3/561.abstract, https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2021.03.200361.

- World Health Organization. “Refugee and Migrant Health.” World Health Organization, 2 May 2022, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/refugee-and-migrant-health.

- Hacker, Karen, et al. “Barriers to Health Care for Undocumented Immigrants: A Literature Review.” Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, vol. 8, no. PMC4634824, 30 Oct. 2015, p. 175, https://doi.org/10.2147/rmhp.s70173.

- Martinez, Omar, et al. “Evaluating the Impact of Immigration Policies on Health Status among Undocumented Immigrants: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, vol. 17, no. 3, 28 Dec. 2013, pp. 947–970, link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10903-013-9968-4, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-013-9968-4.

- Shahin, Wejdan, et al. “The Role of Refugee and Migrant Migration Status on Medication Adherence: Mediation through Illness Perceptions.” PLOS ONE, vol. 15, no. 1, 10 Jan. 2020, p. e0227326, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227326. Accessed 27 Apr. 2020.

- Richter, Kneginja, et al. “Sleep Disorders in Migrants and Refugees: A Systematic Review with Implications for Personalized Medical Approach.” EPMA Journal, vol. 11, no. 2, 1 June 2020, pp. 251–260, link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs13167-020-00205-2#citeas, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13167-020-00205-2.