The Need for Diversity in Clinical Trials

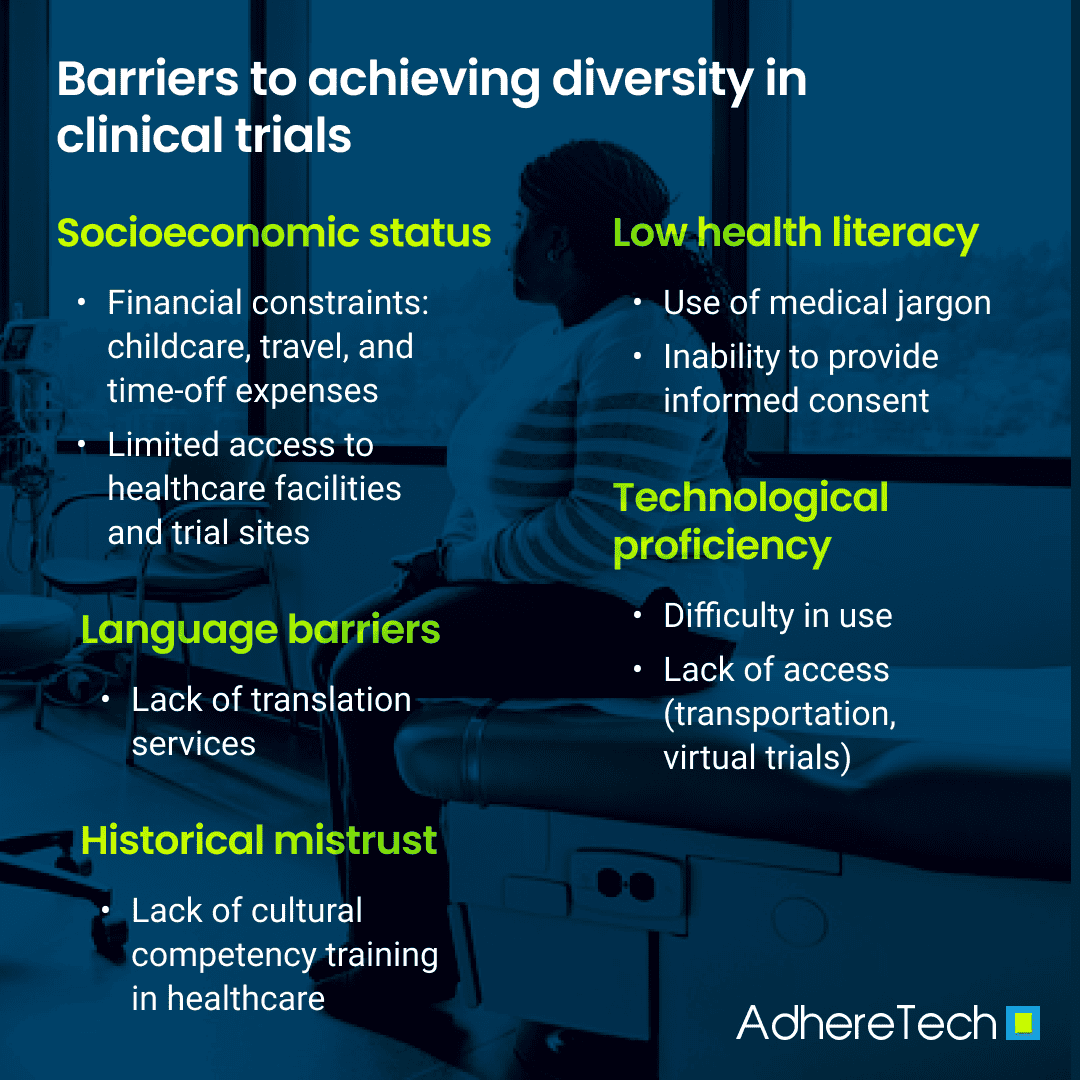

Diversity in clinical trials is critical for enabling research findings within these trials to be generalized to broader populations. By including participants from numerous backgrounds within clinical trials, trial data can accurately reflect the differences in treatment responses across diverse demographic groups, leading to personalized medical interventions and more equitable healthcare outcomes. However, numerous obstacles prevent clinical trials from being inclusive. These challenges can be categorized into financial, cognitive, language, communication, and cultural barriers (Bodicoat et al., 2021; Mapes et al., 2020; Niranjan et al., 2020; Turner et al., 2022). Understanding and addressing these barriers is crucial for developing comprehensive strategies to increase diversity and inclusivity within clinical trials.

It is essential to include diverse participant populations to produce scientific data that is both reliable and generalizable (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine et al., 2022). Without diverse participation, clinical research cannot fully account for the variability in treatment responses across different populations, leading to gaps in care and ineffective treatments for certain groups (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine et al., 2022). Hence, ensuring diversity in clinical trials is necessary for creating reliable and generalizable data that reflects real-world participant populations (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine et al., 2022). Acknowledging the existing barriers and designing trials representing the demographics of all participants receiving these treatments is essential for driving more equitable and effective health outcomes (Corneli et al., 2023).

To address the historical underrepresentation of various populations, numerous efforts have been made to increase these individuals’ enrollment and retention (Corneli et al., 2023). These strategies require proactive planning, with trials actively seeking to address the obstacles that currently limit diversity within clinical trials, such as providing financial support and assistance, enhancing health literacy, providing language translation services, and improving cultural competence among staff involved in clinical trials (Clapp et al., 2024; Corneli et al., 2023; Forum of Neuroscience and Nervous System Disorders et al., 2016).

Existing Barriers to Achieving Diversity in Clinical Trials

The Impact of Low Socioeconomic Status on Clinical Trial Participation and Enrollment

Financial barriers are a substantial challenge to ensuring socioeconomic diversity within clinical trials, with low-income individuals often unable to access clinical trials, likely due to associated costs such as transportation, child care, and time-off work (Bodicoat et al., 2021; Mapes et al., 2020; Niranjan et al., 2020; Turner et al., 2022; Zgierska et al., 2024). Research backs this notion, given that individuals living below the federal poverty level (FPL) are significantly underrepresented in clinical trials (Mapes et al., 2020).

Although sponsors and insurers often cover the expenses associated with participation, many potential participants of low socioeconomic status remain worried about additional trial-related costs, with minor additional costs more likely to affect them than high-income participants (Clark et al., 2019; Maps et al., 2020; Unger et al., 2016). For example, individuals with annual household incomes below $50,0000 were 27% less likely to participate in cancer clinical trials (Schoch, 2023). This is likely because higher-income individuals often have more financial flexibility and resources to participate without concern over these seemingly marginal costs (Unger et al., 2016).

The Challenges Faced by Prospective Participants with Low Health Literacy and Technological Proficiency

Cognitive barriers, such as low health literacy and limited technological proficiency, significantly impede participation in clinical trials. Individuals with low health literacy levels may struggle to understand complex medical terminology and trial protocols, leading to confusion surrounding the trial goals, procedures involved, benefits and risks, and comprehension of informed consent (Berkmen et al., 2011; Bodicoat et al., 2021; Mapes et al., 2020; National Institutes of Health, 2021). Resultantly, they are more likely to feel skeptical or overwhelmed by the clinical trial process, making them less likely to register or remain in trials (Barder et al., 2022).

Furthermore, basic technological proficiency has become increasingly necessary as clinical trials continue to include digital devices for data collection and communication purposes. For example, clinical trials now use mobile apps, online platforms, and electronic devices that track and record various aspects of participants’ health remotely (Inan et al., 2020; Munos et al., 2016). Decentralized trials, which focus on increasing convenience for trial participants by allowing them to participate from home, rely heavily on these digital medical and medication technologies (FDA, 2023). However, in order for these to be effective, they should integrate seamlessly into the participant’s existing life schedule to prevent additional participant burden, potentially discouraging trial engagement. Unfortunately, those who feel uncomfortable using or do not have access to technology, such as older low-income individuals and individuals living in rural locations, may decline to participate or not receive opportunities to participate in clinical trials (Curtis et al., 2022; Mubarak et al., 2022).

The Tribulations of Trial Accessibility for Non-English Speakers

Language barriers further hinder the inclusion of diverse populations within clinical trials. Non-English speakers may find it challenging to comprehend trial information and consent forms when translation resources are unavailable, discouraging them from participating in clinical trials (Mapes et al., 2020; Niranjan et al., 2020). This obstacle is increasingly pronounced for recent immigrants and non-native English speakers. For instance, research highlights that immigrant communities often have fears of deportation, a lack of available clinical trials, and language barriers, decreasing immigrant participants’ understanding of and comfortability with participating in the clinical trial process (Arevalo et al., 2016; Quay et al., 2017). Additionally, while Spanish translation resources are more commonly available in the US than those for other languages, diversity within Hispanic communities causes divergence in understanding the translations of healthcare terminology (Arevalo et al., 2016). Furthermore, translation services are often limited for individuals whose native language is not English or Spanish, such as individuals who identify as South Asian (Quay et al., 2017). As a result, this population is frequently excluded from clinical trials due to language barriers and a lack of available translation services.

Historical Distrust Among Minority Groups Contributes to Persisting Medical Mistrust

Pre-existing lack of trust in medical institutions, varying communication styles, and lacking cultural competence within the medical and healthcare systems contribute to deterring diverse populations from participating in clinical trials (Bodicoat et al., 2021; Maina et al., 2018; Mapes et al., 2020; Niranjan et al., 2020). Underrepresented groups, especially those identifying as Black, rural residing, or sexual/gender minorities, have a historical distrust of clinicians and clinical trials due to unethical practices in prior clinical trials and ongoing discrimination. For instance, the Tuskegee Syphilis Study was one of numerous studies utilizing inhumane practices, which disproportionately impacted Black Americans, leaving a lasting effect on their willingness to participate in medical research in the modern day (McCallum et al., 2006). Similarly, numerous conversion therapy studies were conducted on LGBTQ+ participants, often including harmful procedures that violated the rights of participants by treating their identities as pathological (Trispiotis & Purshouse, 2021). Unfortunately, even in the modern day, many healthcare organizations lack comprehensive cultural competency training, with 53% of organizations reported to have minimal training and activities on cultural competency, such as educational materials in different languages or online training offerings aimed at reducing disparities (Peek et al., 2021). Correspondingly, the scarcity of cultural competence within healthcare dissuades many minority populations from enrolling in clinical trials.

References

Arevalo, M., Heredia, N. I., Krasny, S., Rangel, M. L., Gatus, L. A., McNeill, L. H., & Fernandez, M. E. (2016). Mexican-American perspectives on participation in clinical trials: A qualitative study. Contemporary clinical trials communications, 4, 52-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2016.06.009.

Berkman, N. D., Sheridan, S. L., Donahue, K. E., Halpern, D. J., & Crotty, K. (2011). Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Annuals of internal medicine, 155(2), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005.

Bodicoat, D. H., Routen, A. C., Willis, A., Ekezie, W., Gillies, C., Lawson, C., … & Khunti, K. (2021). Promoting inclusion in clinical trials—a rapid review of the literature and recommendations for action. Trials, 22, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-021-05849-7.

Clapp, L., Henderson-Williams, L., & Whitehead, D. (2024). Diversity and inclusion in clinical trials: Tangible progress and strategies for the future. Applied Clinical Trials. https://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/view/diversity-and-inclusion-in-clinical-trials-tangible-progress-and-strategies-for-the-future

Clark, L. T., Watkins, L., Piña, I. L., Elmer, M., Akinboboye, O., Gorham, M., … & Regnante, J. M. (2019). Increasing diversity in clinical trials: overcoming critical barriers. Current problems in cardiology, 44(5), 148-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2018.11.002.

Corneli, A., Hanlen-Rosado, E., McKenna, K., Araojo, R., Corbett, D., Vasisht, K., Siddiqi, B., Johnson, T., Clark, L. T., & Calvert, S. B. (2023). Enhancing Diversity and Inclusion in Clinical Trials. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics, 113(3), 489–499. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.2819.

Curtis, M. E., Clingan, S. E., Guo, H., Zhu, Y., Mooney, L. J., & Hser, Y. I. (2022). Disparities in digital access among American rural and urban households and implications for telemedicine‐based services. The Journal of Rural Health, 38(3), 512-518.

Food & Drug Administration (FDA). (2023). The evolving role of decentralized clinical trials and digital health technologies. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/cder-conversations/evolving-role-decentralized-clinical-trials-and-digital-health-technologies#:~:text=DCTs%20and%20DHTs%20may%20help,access%20to%20research%20for%20them.

Forum on Neuroscience and Nervous System Disorders; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Neuroscience Trials of the Future: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2016 Aug 19. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK379506/doi: 10.17226/23502

Georgetown University: Center for Child and Human Development. (n.d.). Cultural competence. Georgetown University. https://gucchd.georgetown.edu/cultural-competence.php

Inan, O. T., Tenaerts, P., Prindiville, S. A., Reynolds, H. R., Dizon, D. S., Cooper-Arnold, K., … & Califf, R. M. (2020). Digitizing clinical trials. NPJ digital medicine, 3(1), 101.

Maina, I. W., Belton, T. D., Ginzberg, S., Singh, A., & Johnson, T. J. (2018). A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Social science & medicine, 199, 219-229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.009.

Manti, S., & Licari, A. (2018). How to obtain informed consent for research. Breathe (Sheffield, England), 14(2), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.001918.

Mapes, B. M., Foster, C. S., Kusnoor, S. V., Epelbaum, M. I., AuYoung, M., Jenkins, G., … & All of Us Research Program. (2020). Diversity and inclusion for the All of Us research program: A scoping review. PloS one, 15(7), e0234962. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234962.

McCallum, J. M., Arekere, D. M., Green, B. L., Katz, R. V., & Rivers, B. M. (2006). Awareness and knowledge of the US Public Health Service syphilis study at Tuskegee: implications for biomedical research. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, 17(4), 716-733. Doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0130.

Mubarak, F., & Suomi, R. (2022). Elderly forgotten? Digital exclusion in the information age and the rising grey digital divide. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, 59, 00469580221096272.

Munos, B., Baker, P. C., Bot, B. M., Crouthamel, M., de Vries, G., Ferguson, I., … & Wang, P. (2016). Mobile health: the power of wearables, sensors, and apps to transform clinical trials. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1375(1), 3-18.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Policy and Global Affairs; Committee on Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine; Committee on Improving the Representation of Women and Underrepresented Minorities in Clinical Trials and Research; Bibbins-Domingo K, Helman A, editors. Improving Representation in Clinical Trials and Research: Building Research Equity for Women and Underrepresented Groups. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2022 May 17. 2, Why Diverse Representation in Clinical Research Matters and the Current State of Representation within the Clinical Research Ecosystem. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK584396/

National Institutes of Health. (2021). Health literacy. NIH: Office of the Director. Retrieved July 17, 2024, from https://www.nih.gov/institutes-nih/nih-office-director/office-communications-public-liaison/clear-communication/health-literacy.

Niranjan, S. J., Martin, M. Y., Fouad, M. N., Vickers, S. M., Wenzel, J. A., Cook, E. D., … & Durant, R. W. (2020). Bias and stereotyping among research and clinical professionals: perspectives on minority recruitment for oncology clinical trials. Cancer, 126(9), 1958-1968. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32755.

Peek, M. E., Wilson, S. C., Bussey-Jones, J., Lypson, M., Cordasco, K., Jacobs, E. A., … & Brown, A. F. (2012). A study of national physician organizations’ efforts to reduce racial and ethnic health disparities in the United States. Academic Medicine, 87(6), 694-700. Doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318253b074.

Quay, T. A., Frimer, L., Janssen, P. A., & Lamers, Y. (2017). Barriers and facilitators to recruitment of South Asians to health research: a scoping review. BMJ open, 7(5), e014889. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014889

Schoch., S. (2023). Patients, poverty, and participation in research: The hidden cost of disease and socioeconomic status. National Health Council. https://nationalhealthcouncil.org/blog/patients-poverty-and-participation-in-research-the-hidden-costs-of-disease-and-socioeconomic-status/.

Trispiotis, I., & Purshouse, C. (2021). ‘Conversion Therapy’ As Degrading Treatment. Oxford journal of legal studies, 42(1), 104–132. https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gqab024.

Turner, B. E., Steinberg, J. R., Weeks, B. T., Rodriguez, F., & Cullen, M. R. (2022). Race/ethnicity reporting and representation in US clinical trials: a cohort study. The Lancet Regional Health–Americas, 11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2022.100252.

Unger, J. M., Gralow, J. R., Albain, K. S., Ramsey, S. D., & Hershman, D. L. (2016). Patient Income Level and Cancer Clinical Trial Participation: A Prospective Survey Study. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3924.

Zgierska, A. E., Gramly, T., Prestayko, N., Symons Downs, D., Murray, T. M., Yerby, L. G., Howell, B., Stahlman, B., Cruz, J., Agolli, A., Horan, H., Hilliard, F., Croff, J. M., & HEALthy Brain and Child Development (HBCD) Consortium (2024). Transportation, childcare, lodging, and meals: Key for participant engagement and inclusion of historically underrepresented populations in the healthy brain and child development birth cohort. Journal of clinical and translational science, 8(1), e38. https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2024.4