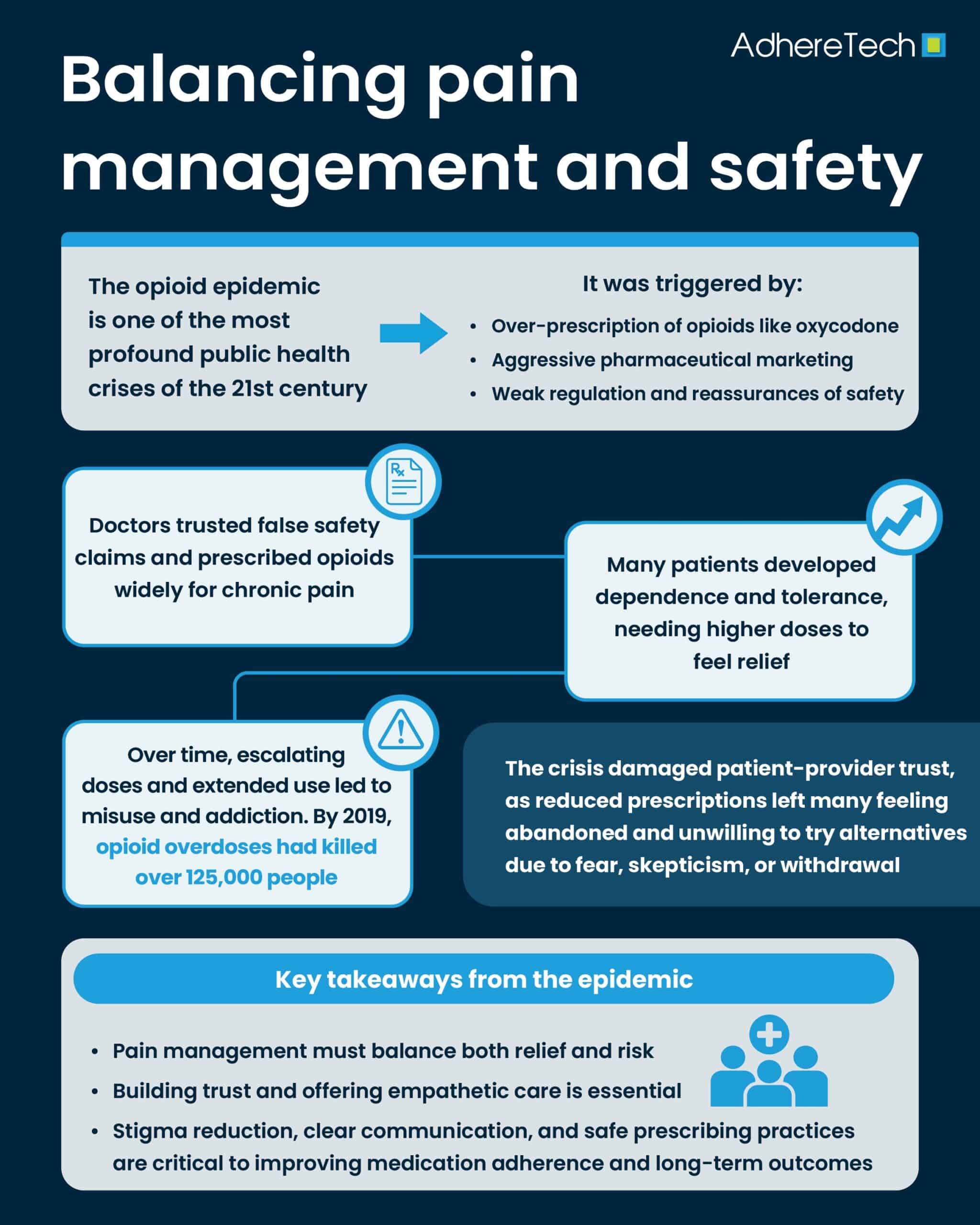

The opioid epidemic is one of the most profound public health crises of the 21st century1. Beginning in the 1990s, the widespread over-prescription of opioid painkillers—coupled with aggressive pharmaceutical marketing and a lack of regulation—set the stage for an era marked by rising addiction rates, overdose deaths, and significant social and economic consequences1. But the epidemic is more than just a tragedy of addiction; it has deeply influenced the way patients interact with prescriptions and medication adherence, complicating both pain management and broader healthcare strategies2.

In the 1990s, pharmaceutical companies began aggressively marketing opioid painkillers as a solution for patients experiencing chronic pain1,2. At the time, opioids like oxycodone, hydrocodone, and morphine were hailed as revolutionary pain management options, offering long-term relief for individuals with conditions such as back pain, arthritis, and cancer2. Doctors were encouraged to prescribe these medications liberally, with assurances that they were safe and non-addictive when used properly1,2. The aggressive marketing campaigns by pharmaceutical companies downplayed the risks of addiction, and many healthcare providers were not fully aware of the dangers these medications posed3. As a result, opioid prescriptions skyrocketed, and what began as a solution to pain quickly turned into a widespread addiction problem2,3.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 125,000 people died of opioid overdoses in 2019 alone3. Many of these overdoses started with legal prescriptions, which were written in good faith to help patients manage pain1,3. However, over time, the ease with which patients could obtain these drugs and the growing dependence on them created a perfect storm for the opioid epidemic3. At the heart of the opioid crisis is the way in which the over-prescription of pain medications affected patient adherence to prescriptions1-3. While the initial goal of pain medication prescriptions was to alleviate suffering, over-prescribing opioids led to an unfortunate trend: patients not only became physically dependent on the drugs but also often misusing them3.

For many, the immediate pain relief brought by opioids overshadowed the long term consequences, such as an increasing tolerance (the need for higher doses over time to achieve the same effect(s)5) and physical dependence (experiencing withdrawal symptoms when the drug is stopped6)1-4. As a result, patients found themselves needing more prescriptions, leading to escalating doses and extended use. In many cases, this cycle led to addiction2-4. What started as adherence to a prescribed medication regimen morphed into self-destructive behaviors, such as doctor shopping, where individuals would visit multiple doctors to obtain additional prescriptions, or turning to illegal sources to procure opioids3-4.

This phenomenon was exacerbated by the stigma that patients with chronic pain and addiction often faced7. Many people were reluctant to seek help for their opioid misuse out of fear of judgment, and instead, they continued to seek out prescriptions from illegal sources, contributing to both addiction and worsening physical health7. This stigma associated with opioid abuse can cause patients to underreport symptoms or avoid care altogether, further compromising adherence to prescribed therapies8. The epidemic has thus complicated the delicate balance between managing pain effectively and preventing substance misuse, ultimately disrupting consistent and effective medication use.

Another significant consequence of the over-prescription of opioids has been the erosion of trust between healthcare providers and patients9. Historically, doctors have been viewed as the primary authority on medical decisions, and their advice was often followed without question. However, as the opioid epidemic progressed, many patients became disillusioned when they realized that the medications they had been prescribed were contributing to their physical and emotional decline9. For patients who had become dependent on opioids, their sense of trust in the healthcare system eroded further when doctors, in response to the crisis, began to limit opioid prescriptions or abruptly discontinue them. This shift felt like abandonment, and it often led to more dangerous coping mechanisms, such as turning to illicit drugs like heroin3,8. The lack of continuity and empathetic care in the transition away from opioids has made it difficult for patients to adhere to new pain management strategies, as they often feel misunderstood or neglected by their providers9. As a result, when doctors attempt to reduce opioid prescriptions in favor of alternatives, patients may resist or even abandon the new treatments in favor of the only solution that feels familiar: opioids3,4. This reluctance is often tied to the fear of withdrawal symptoms or the belief that the alternatives will not provide the same level of relief3. This poses a significant barrier to adherence to new pain management plans, further exacerbating the cycle of opioid dependence10.

While the over-prescription of opioids in the 1990s and early 2000s remains a major public health issue, there are important lessons to be learned for future pain management and prescription practices. The opioid epidemic has highlighted the need for a balanced approach to pain management—one that minimizes the risk of addiction while ensuring that patients’ pain is managed effectively.

References

- Xianhua Zai. “Beyond the Brink: Unraveling the Opioid Crisis and Its Profound Impacts.” Economics & Human Biology/Economics and Human Biology, vol. 53, 1 Apr. 2024, pp. 101379–101379, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2024.101379.

- Phillips, Jonathan K, et al. “Evidence on Strategies for Addressing the Opioid Epidemic.” Nih.gov, National Academies Press (US), 13 July 2020, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK458653/.

- World Health Organization. “Opioid Overdose.” World Health Organization, 29 Aug. 2023, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/opioid-overdose.

- GOV.UK. “Opioid Medicines and the Risk of Addiction.” GOV.UK, 2020, www.gov.uk/guidance/opioid-medicines-and-the-risk-of-addiction.

- Lynch, Shalini S. “Tolerance and Resistance to Medications.” MSD Manual Consumer Version, MSD Manuals, 6 Mar. 2025, www.msdmanuals.com/home/drugs/factors-affecting-response-to-medications/tolerance-and-resistance-to-medications.

- National Cancer Institute. “Https://Www.cancer.gov/Publications/Dictionaries/Cancer-Terms/Def/Physical-Dependence.” Www.cancer.gov, 2 Feb. 2011, www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/physical-dependence.

- Committee on the Science of Changing Behavioral Health Social Norms. “Understanding Stigma of Mental and Substance Use Disorders.” National Library of Medicine, National Academies Press (US), 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK384923/.

- Cheetham, Ali, et al. “The Impact of Stigma on People with Opioid Use Disorder, Opioid Treatment, and Policy.” Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, vol. 13, no. 13, 2022, pp. 1–12, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35115860/, https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S304566.

- Somohano, Vanessa C, et al. “Patient-Provider Shared Decision-Making, Trust, and Opioid Misuse among US Veterans Prescribed Long-Term Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain.” Journal of General Internal Medicine, vol. 38, no. 12, 28 Apr. 2023, pp. 2755–2760, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08212-5. Accessed 13 Jan. 2024.

- Marashi, Amir, et al. “Trends in Opioid Medication Adherence during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Retrospective Cohort Study.” JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, vol. 9, 1 Sept. 2023, pp. e42495–e42495, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10504620/, https://doi.org/10.2196/42495. Accessed 15 Apr. 2025.