Using Biofeedback to Understand Medication Response in Real Time

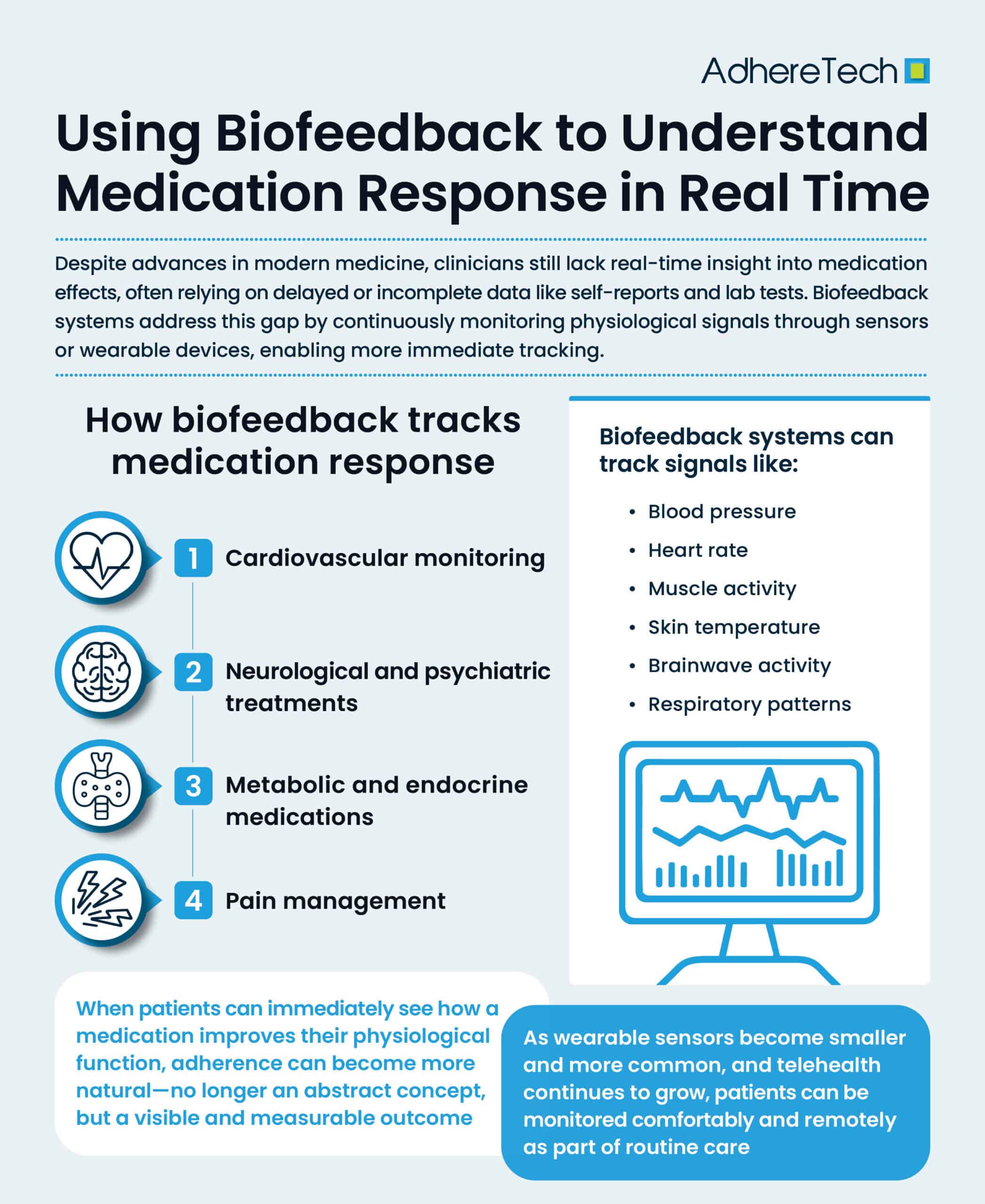

The advancement of modern medicine has revolutionized how we treat disease, yet one major limitation persists: we know very little about how patients respond to medications in real time.1 Traditionally, clinicians rely on retrospective observations, such as patient self-reporting or scheduled lab tests, to evaluate whether a treatment is effective.2 However, these methods frequently leave providers with an incomplete picture of a patient’s health— tools collecting biofeedback data, physiological signals from the body, offer a promising solution.2 By continuously monitoring measurable biological responses within the body, biofeedback systems can help clinicians and patients track how the body reacts to medications on a moment-to-moment basis.3 Using sensors placed on the skin or integrated into wearable devices, biofeedback systems can track signals such as:3

- Heart rate and heart rate variability/abnormalities

- Blood pressure

- Skin temperature

- Muscle activity (electromyography)

- Brainwave activity (electroencephalography)

- Respiratory patterns

The core idea is that biological processes that are normally measured once on a routine basis (every few weeks to months typically) can be measured in real-time.3 In traditional settings, biofeedback has been used to help patients manage stress, migraines, and chronic pain by giving them insight into how their body reacts to different stimuli, environments, and even medications.3 Today, with significant, continual advances in digital health and wearable sensors, this concept is evolving into a powerful tool for medication monitoring.

The Need for Real-Time Medication Insights

While there is a general misconception that medications impact all patients the same, each patients’ body responds differently to their medications. Factors like genetics, diet, co-existing conditions, and lifestyle can alter drug absorption, metabolism, and effectiveness.4 Some patients experience side effects that discourage adherence, while others fail to notice improvements in their symptoms, which can oftentimes require weeks or months of consistent treatment adherence.4 Both adverse side effects and non-tangible treatment benefits can significantly reduce the likelihood of patients’ taking their medication.5

Conventional methods of tracking medication response—such as quarterly lab results or patient diaries—cannot capture these variations, providing only a snapshot into each patients’ adherence data.1 For instance, blood draws only reliably detect medication adherence within the recent days preceding their clinical visit. Likewise, patient diaries are subject to inadvertent (forgetting to record whether they consumed their medications or not) and advertent inaccuracy biases (choosing to report adherence to treatment, even if untrue). In contrast, biofeedback offers the unique opportunity for continuous monitoring, allowing for the early detection of therapeutic benefits and adverse effects via physiological markers.3 Real-time data ensures that clinicians no longer need to wait until a follow-up appointment to understand whether a medication is truly working and reduces the risk of non-adherence.

How Biofeedback Tracks Medication Response

1. Cardiovascular Monitoring

Medications for hypertension, anxiety, and cardiac conditions often influence heart rate and blood pressure.6 Wearable biofeedback devices, such as discrete smart watches and rings, can monitor these metrics continuously, providing clinicians with a clear profile of how a drug stabilizes or destabilizes cardiovascular function throughout the day based on patient’s dosing time(s).7

2. Neurological and Psychiatric Treatments

Drugs that target the central nervous system, such as antidepressants, antipsychotics, or stimulants, can have subtle and varied effects on brain activity.8 Biofeedback through EEG sensors helps researchers and clinicians measure shifts in brainwave patterns, offering early indicators of whether the medication is producing the intended neurological response.9 However, continuous EEG monitoring currently entails week long hospital stays or surgical implementation, making it burdensome, expensive and intrusive for patients.9

3. Pain Management

Analgesics and muscle relaxants are often prescribed for chronic pain, yet effectiveness can be highly subjective due to psychological processes.10 Biofeedback devices that measure muscle tension and skin conductance offer an objective measure of how the body to pain relief therapies, providing a more reliable measure.3

4. Metabolic and Endocrine Medications

Medications for diabetes or thyroid conditions alter metabolism in ways that are not always immediately visible.11 Continuous glucose monitoring already functions as a form of biofeedback, demonstrating how blood sugar responds to insulin or oral medications in real time.12 Future systems may expand this approach to track other biomarkers linked to hormone regulation.

Benefits of Real-Time Biofeedback in Medication Management

Biofeedback offers a powerful way to personalize treatment by giving clinicians real-time data about a patient’s responses.3 Instead of depending on population averages, providers can adjust dosages more precisely and quickly, tailoring medication regimens to each individual.3 When patients can immediately see how a medication improves their physiological function, adherence can become more natural—no longer an abstract concept, but a visible and measurable outcome. This same continuous feedback can reveal early warning signs of adverse effects, such as sudden heart rate spikes or irregular breathing, that may otherwise go unreported between appointments,3 possibly increasing the likelihood of non-adherence.

Just as importantly, biofeedback places patients in control of their own care.3 By making hidden physiological processes visible, it empowers them to engage actively in their treatment plans and strengthens the partnership between patients and their providers by providing tailored treatment approaches.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite its potential, using biofeedback to guide medication response still faces important challenges. Continuous monitoring produces massive amounts of data, which necessitates effective systems that can filter, analyze, and interpret information without overwhelming clinicians.13 Accuracy and reliability are equally critical, as many devices on the market have not been FDA approved, and inconsistent readings could undermine trust or lead to incorrect decisions.13 There are also risks associated with the use of artificial intelligence in these systems; if an AI model is not appropriately trained, it can lead to hallucinations such as false positives, which could compromise patient safety and treatment outcomes.14 Privacy is another concern, as constant data collection and transmission demand robust protections for ensuring security and patient consent.3 Accessibility also poses a barrier: wearable devices can be expensive, and unequal access risks widening existing healthcare disparities, particularly for those of low socio-economic status.15 Finally, integrating biofeedback into clinical workflows remains difficult, especially for practices already burdened by electronic health record management.16 Thoughtful implementation will be essential to ensure this technology enhances care rather than adding administrative strain.

The Future of Biofeedback in Medicine

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) with biofeedback represents an exciting frontier. AI algorithms can sift through complex datasets, identifying patterns that may not be immediately visible to human observers.17 For example, machine learning could detect subtle variations in heart rate variability that predict whether a patient will benefit from a particular cardiovascular medication.17

In addition, miniaturized sensors are making biofeedback more accessible and user-friendly. Smartwatches, adhesive patches, and even contact lenses are being developed to provide continuous, unobtrusive monitoring.18 As these devices become more common, biofeedback will likely shift from only being provided in specialized therapy rooms to an integral part of everyday life.

Moreover, the rise of telehealth creates opportunities for remote monitoring. Patients in rural or underserved areas can transmit biofeedback data to providers without needing frequent in-person visits.15 This makes real-time medication monitoring scalable across diverse patient populations.

Ethical Considerations

While the potential is vast, the use of biofeedback for medication monitoring raises ethical questions. Should providers expect patients to wear devices 24/7? Who owns the data generated, and how should it be stored or shared? Balancing innovation with autonomy and privacy will be essential.

Furthermore, providers must ensure that biofeedback does not replace human judgment.18 While sensors and algorithms provide valuable insights, clinical expertise remains indispensable in interpreting and contextualizing the data.

Biofeedback represents a powerful tool for understanding how patients respond to medications in real time. By making physiological responses visible and measurable, it allows clinicians to personalize treatments, detect side effects early, and empower patients to engage more actively in their care. Although challenges such as data management, device accuracy, and privacy remain, the trajectory of technological innovation suggests these obstacles will be addressed with time.

Ultimately, biofeedback has the potential to transform medication management from a reactive process into a proactive, dynamic partnership between patient and provider. In the future, taking a pill may no longer be an act of faith—patients and clinicians alike will have immediate evidence of whether the treatment is doing what it is supposed to do.

References

- Ahmed, Shabbir, et al. “Pharmacogenomics of Drug Metabolizing Enzymes and Transporters: Relevance to Precision Medicine.” Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics, vol. 14, no. 5, Oct. 2016, pp. 298–313, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2016.03.008.

- Alorfi, Nasser M. “Pharmacological Methods of Pain Management: Narrative Review of Medication Used.” International Journal of General Medicine, vol. 16, no. 16, 2023, pp. 3247–3256, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10402723/, https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S419239.

- Balogh, Erin P, et al. “The Diagnostic Process.” Nih.gov, National Academies Press (US), 2020, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK338593/.

- Baryakova, Tsvetelina H., et al. “Overcoming Barriers to Patient Adherence: The Case for Developing Innovative Drug Delivery Systems.” Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, vol. 22, no. 22, 27 Mar. 2023, pp. 1–23, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-023-00670-0.

- Celano, Christopher M., et al. “Anxiety Disorders and Cardiovascular Disease.” Current Psychiatry Reports, vol. 18, no. 11, 26 Sept. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5149447/, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-016-0739-5.

- Dias, Duarte, and João Paulo Silva Cunha. “Wearable Health Devices—Vital Sign Monitoring, Systems and Technologies.” Sensors, vol. 18, no. 8, 25 July 2018, p. 2414, www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/18/8/2414, https://doi.org/10.3390/s18082414.

- Dibonaventura, Marco, et al. “A Patient Perspective of the Impact of Medication Side Effects on Adherence: Results of a Cross-Sectional Nationwide Survey of Patients with Schizophrenia.” BMC Psychiatry, vol. 12, no. 20, 20 Mar. 2012, p. 20, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22433036, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-20.

- Eom, Young Sil, et al. “Links between Thyroid Disorders and Glucose Homeostasis.” Diabetes & Metabolism Journal, vol. 46, no. 2, 31 Mar. 2022, pp. 239–256, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8987680/, https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2022.0013.

- Frank, Dana L, et al. “Biofeedback in Medicine: Who, When, Why and How?” Mental Health in Family Medicine, vol. 7, no. 2, June 2010, p. 85, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2939454/.

- Khalifa, Mohamed, and Mona Albadawy. “Artificial Intelligence for Clinical Prediction: Exploring Key Domains and Essential Functions.” Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine Update, vol. 5, 1 Mar. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpbup.2024.100148.

- Khatiwada, Pankaj , et al. “Patient-Generated Health Data (PGHD): Understanding, Requirements, Challenges, and Existing Techniques for Data Security and Privacy.” Journal of Personalized Medicine, vol. 14, no. 3, 3 Mar. 2024, pp. 282–282, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10971637/, https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14030282.

- Malik, Kashif, and Anterpreet Dua. “Biofeedback.” PubMed, StatPearls Publishing, 2021, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553075/.

- Marzbani, H., et al. “Neurofeedback: A Comprehensive Review on System Design, Methodology and Clinical Applications.” Basic and Clinical Neuroscience Journal, vol. 7, no. 2, Apr. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4892319/, https://doi.org/10.15412/j.bcn.03070208.

- Team Scrut. “AI Hallucination: When AI Experiments Go Wrong.” Scrut.io, Scrut Automation, 2 Jan. 2024, www.scrut.io/post/ai-hallucinations-grc.

- Mayo Clinic. “Biofeedback – Mayo Clinic.” Mayoclinic.org, 18 Mar. 2023, www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/biofeedback/about/pac-20384664.

- National Library of Medicine. Chapter 2—How Stimulants Affect the Brain and Behavior. Www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US), 2021, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK576548/.

- Ranganathan, C, et al. “Exploring Disparities in Healthcare Wearable Use among Cardiovascular Patients: Findings from a National Survey.” Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine, vol. 24, no. 11, 9 Nov. 2023, pp. 307–307, https://doi.org/10.31083/j.rcm2411307.

- Russell, Steven. “Continuous Glucose Monitoring.” National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2023, www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/managing-diabetes/continuous-glucose-monitoring.

- Thakkar, Anoushka, et al. “Artificial Intelligence in Positive Mental Health: A Narrative Review.” Frontiers in Digital Health, vol. 6, no. 1280235, 18 Mar. 2024, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10982476/, https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2024.1280235.