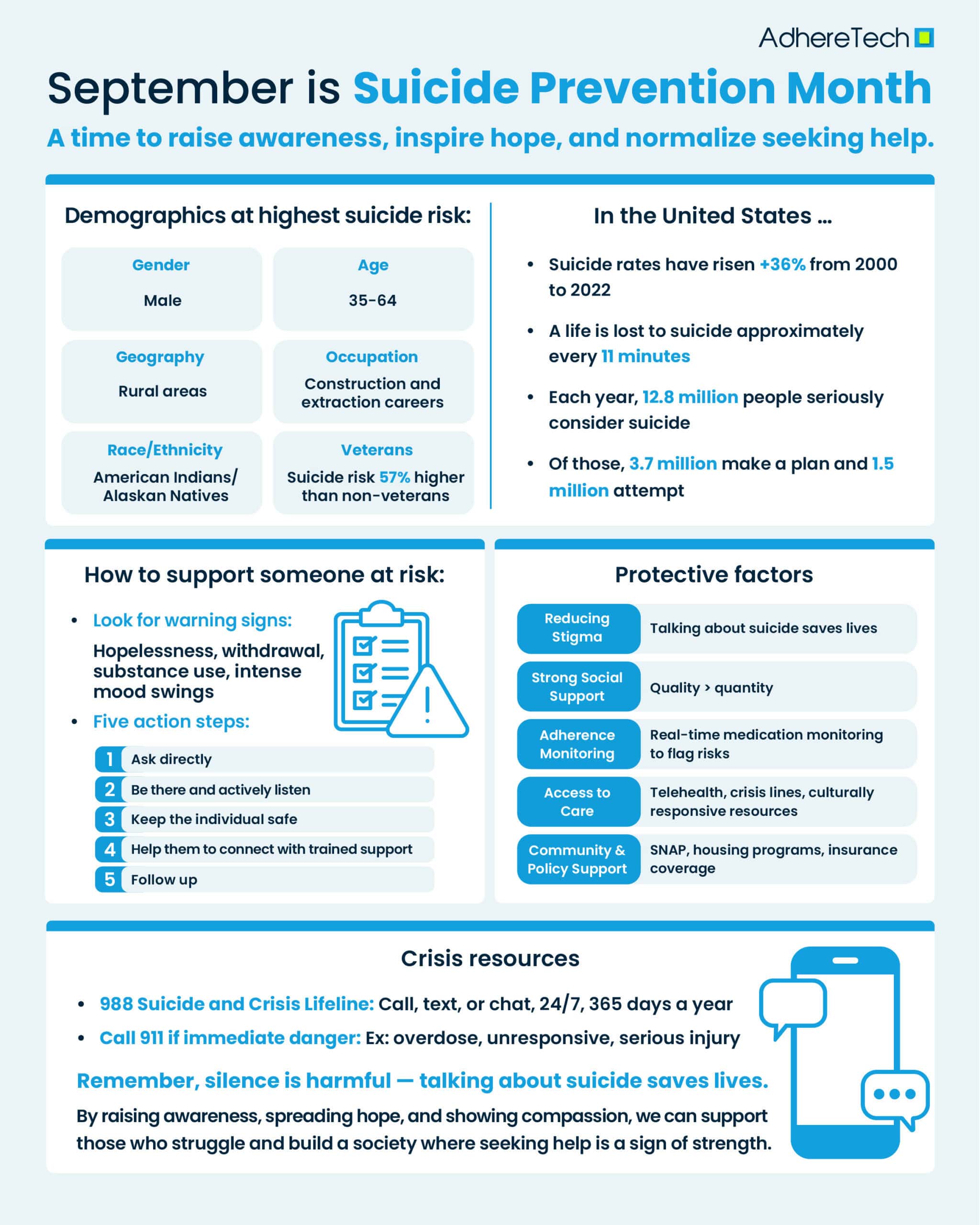

September marks National Suicide Prevention Month, a month dedicated to raising awareness, inspiring hope, and normalizing seeking out help when needed.1

Suicide, defined as death caused by harming oneself with the intention of ending their life, has been deemed as a public health crisis. In the United States, suicide rates have risen by 36% from 2000 to 2022, resulting in suicide being one of the top eight leading causes of death within the United States for individuals aged 10 through 64.2 In 2023, suicide was responsible for over 49,000 deaths – that’s one death every 11 minutes, or an estimated 134 deaths per day.2 More concerningly, over 12.8 million people have reported that they have seriously contemplated suicide, 3.7 million have made a plan, and 1.5 million have attempted.2

The consequences of suicide and suicide attempts are far-reaching. Individuals who attempt suicide and survive can experience injuries that have long-term, negative impacts on their physical and mental health.2 These impacts cascade, often harming the well-being of friends, loved ones, co-workers, and communities, often leading to prolonged feelings of grief, anger, guilt, shock, mental health issues, and in some cases, even suicidal ideation.2 Moreover, the cost of suicide and non-fatal self harm in the United States is an estimated $510 billion dollars annually, accounting for medical costs, lost work costs, etc.3

Given the high prevelance of suicide throughout society – and it’s detrimental personal, social, and economic impacts – it is critical to not only recognize at risk populations, but explore and address key risk factors associated with suicide and suicidal ideation.

Groups Disproportionately Impacted (Based on CDC Data from 2021)

Gender

- Males make up 50% of the American population, but account for nearly 80% of suicides (Males: 22.7 per 100,000, Females: 5.9 per 100,000).4

- Potential Reasons: Often lower levels of willingness to engage in mental health help seeking, higher rates of mental health strigma, higher rates of impulsivity, lack of gender-sensitive services for mental health, higher rates of alcohol and drug use, and higher rates of access and use of lethal means.5

Age

- 46.8% of all suicides in the United States occur in adults ages 35 to 64.6

Race and Ethnicity

- Age-adjusted suicide rates are highest among Non-Hispanic American Indians and Alaskan Natives (28.1 per 100,000).6

Veteran Status

- Age-adjusted suicide rates are 57.3% higher among veterans when compared to the non-veteran American adult population.6

Geographic Region

- Suicide rates increase as population density declines, with those living in rural (non-metro) areas having the highest rates (Large Metro: 11.6 per 100,000; Non Metro: 21.7 per 100,000).6

- Potential Reasons: Social isolation, easier access to lethal means, increased stigma towards those with mental health challenges, and lower mental health service availability.12

Occupation

- Individuals working in construction and extraction have higher suicide rates than the general population (Males: 49.4 per 100,000; Females: 25.5 per 100,000).6

- Potential Reasons: High stress work environment, emphasis on traditional gender roles (mental and physical “toughness”), job instability, higher risk of physical exhaustion and injuries, and elevated levels of opioid misuse.13

Barriers to Seeking Help

Stigma Against Suicide and Mental Health

Experiencing suicide-related stigma is commonly associated with a lower likelihood of seeking out mental health care and a higher risk of suicide.14 Suicide-related stigma encompasses public (external), internal, and perceived or anticipated stigma.14 Regarding public perceptions, when individuals view mental health or people struggling with mental illnesses unfavorably, this can lead to them devaluing said individual’s worth as a person.14 Unfortunately, many individuals internalize these perceptions, which can lead to self-isolation, in addition to feelings of worthlessness, shame, and fear, all of which can further reduce an individual’s likelihood of seeking out the appropriate mental health services.14

Lack of Effective Social Support Systems

Lacking established social connections and relationships can increase depressed patient’s risk of suicide, even more than the impact of depression on suicide alone.15, 16

Social support is defined as one’s perceptions that others, such as family, friends, and significant others, are able to offer psychological and physical care.16 However, the frequency of direct contact with members of ones support system does not automatically translate to feelings of connectedness or support, rather one’s perception of the quality of their relationships is believed to be a far more powerful, protective factor.16 This suggests that to effectively reduce the risk of suicide, individuals must not only engage in social interactions, but have established relationships with members of their support system that they believe can offer them effective mental and physical support.16

Unfortunately, individuals living with major depressive disorder, whose likelihood of dying by suicide is 8.22 times greater than that of the general population, often exhibit significant impairments in their social cognition when compared with other neuropsychiatric disorders.17, 18 Studies have shown that when unfamiliar adolescents interacted with clinically depressed and non-depressed individuals, they believed depressed individuals were less interested in establishing a friendship, resulting in them being less motivated to pursue developing a relationship with them.19 Moreover, the interpersonal theory of depression suggests that individuals living with depression often withdraw from social situations, excessively seek out reassurance, or express their negative emotions inappropriately, leading them to experience perceptions of social rejection, which increases their risk of social isolation.19 This suggests that having a diagnosis of clinical depression impairs social functioning, making it increasingly difficult for individuals at risk of suicide to establish and maintain protective social relationships.

Increases in Medication Non-Adherence

An estimated 24-28% of suicide victims become non-adherent to their medication regimens within the month before their death.20 Unfortunately, research indicates 46% of individuals who die by suicide had a diagnosed mental health condition at the time of their death.21 Psychopharmacological treatments are often prescribed to patients with mental health disorders, with estimates suggesting non-adherence rates range from 40-60% among psychiatric patient populations.20 Consequently, persistent non-adherence may serve as a critical warning sign for individuals at risk of suicide, especially if they have a history of prior suicidal ideation or attempts. Traditional methods of adherence monitoring are often inaccurate and retrospective, highlighting the need for solutions that ensure providers have access to accurate, real-time adherence data to identify at-risk patients and proactively intervene.

Low Socioeconomic Status

Income poses a major challenge for individuals struggling with suicidal ideations. While many of these individuals may be motivated to seek out help, they may lack the necessary financial resources to do so. Research has shown significant associations between unemployment and suicide risk, with the American National Health Interview Survey finding a 45% increased risk of death by suicide among unemploymed versus employed individuals.22 While unemployment can lead to significant financial strains which make it exceedingly challenging to get the support they need, the loss of work-related social relationships also appears to contribute to the increased risk among this population.22

Insufficient health insurance coverage is a key contributer as well, with suicide rates 26% lower in contries with the most coverage compared to those with the least.23 For those with suicidal ideations and plans to act on them, psychiatric hospitalization or inpatient services may be deemed necessary. The associated costs typically range from $500 to $2000 dollars per day, with estimated costs of $15,000 to $60,000 for a standardized 30-day stay.24 For those without health insurance, these hefty costs are often completely unaffordable, and even for those with health insurance, high out of pocket costs or co-pays may serve as a preventative barrier.

Limited Resource Availability

Residing in rural or underdeveloped areas can severely limit accessibility to mental health services due to limited resources, professionals, and specialized services.25 Without services widely advertised in the community, individuals may be unaware of where to turn for help.25 Moreover, even for those aware of such services, the extensive travel time associated with reaching the closest facilities may be infeasible.25

While telehealth services have expanded mental health accessibility for those residing in rural or underdeveloped areas, a series of challenges still exist.25 Some individuals do not possess the technology or technological literacy necessary to access telehealth.25

Cultural Dynamics

Both regional and religious differences appear to play a significant role in help-seeking for suicidal ideations or behaviors.25 Countries and regions have varying availability and awareness of specialized psychological care services. For those with limited resources, mental health may be more heavily stigmatized or individuals may be skeptical of such services, reducing their likelihood of seeking them out support.25 Moreover, different cultural values influence perceptions of self-reliance, with some encouraging seeking help and others viewing help-seeking as a weakness.25 For instance, Chinese culture frequently encourages self-reliance and informal support, both of which can decrease the likelihood of individuals seeking out professional help.25 Similarly, American values often encourage individualism, being independent and self-reliant, a theoretical principle that has been associated with increased risk of suicide and suicidal ideation.26

Religion also plays a large role in attitudes towards suicide, with many religions often disapproving or prohibiting suicide. Although religious values can serve as a deterrent for committing suicide, these beliefs may also result in a fear of ostracization or dissapproval, preventing individuals from discussing their struggles and seeking out necessary support.

For example, Islam strictly prohibits suicide, with certain countries considering suicide or suicide attempts as a criminal offense.27 Christianity has long held the belief that suicide is a sin.27 However, for an act to be deemed a sin in Christianity, the individual must be mentally competent, which may blur perspectives if one views suicide as an act of someone who is mentally ill.27 Similarly, traditional Judiasm considered suicide as a criminal act with severe spirtual consequences, however, in the modern day it is often viewed more compassionately, considered to be an act of someone struggling with mental illness.27 While Hinduism discourages suicide, referred to as an abandonment of life, the ideology of death signaling rebirth have led some to suggest suicide may considered more tolerantly than other religions.27

Consequently, while major world religions often prohibit suicide, their teachings and cultural interpretations can have complex effects – deterring some from self-harm, but also discouraging others from reaching out for the support they need. When paired with the criminalization of suicide, these dynamics may further isolate individuals, increasing their risk as oppossed to reducing it.

Facilitators to Seeking Support and Supporting Loved Ones

Reducing Stigma

Reducing the stigma surrounding suicide requires addressing widespread societal misconceptions. For instance, many people consider suicide as an act of selfishness, considering it as “taking the easy way out.”28, 29 In reality, individuals experiencing suicidal ideations or engaging in harmful self behaviors frequently feel so helpless and hopeless that they believe suicide is their only option.29 These individuals are not only thinking of themselves, but often believe those around them would be better off without them.

Similarly, there is the common misbelief that suicide only impacts individuals with mental health conditions.29 Yet, life stressors, relationship issues, grief, abuse, and crises have all been associated with suicidal ideations and attempts, with an estimated 54% of people passing from suicide not having a diagnosable mental health disorder.29 Unfortunately, this misconception has led many to believe that once an individual becomes suicidal, they will always remain suicidal.29 Active suicidal ideation and behaviors are often short-term and situationally-specific, and although these thoughts can return, they are not permanent.29 In fact, 90% of people who attempt suicide, do not die by suicide, emphasizing that with the correct services and support in place, individuals can recover and lead fulfilling lives.30

The widespread stigma surrounding suicide contributes to people being afraid to discuss it openly.29 Yet, research shows that discussions surrounding suicide not only reduce stigma, but also help individuals seek help, rethink their options, and share their experiences with others.29 To successfully begin dismantling the stigma surrounding suicide, society must begin talking about it more openly and continue to advocate for mental health awareness, especially among at-risk populations. In doing so, conversations can be approached compassionately and effectively, offering better support to those in need.

How Can We Support Individuals Struggling with Suicidal Ideations and/or Behaviors?

Literature consistently highlights that strong social support serves as a protective factor against suicide.15 As previously mentioned, the perceived quality of support is far more important than perceptions regarding the quantity of support.16 So how can we effectively support those who may be struggling?

- Be Aware of the Warning Signs31

- Expressing feelings of hopelessness, feeling trapped, being a burden to others, or wanting to die.

- Increased use of alcohol and/or drugs.

- Increased anxiety, agitation, and/or mood swings.

- Sleeping too much or too little.

- Social withdrawal or isolation.

- The Five Action Steps31

- Ask the question, “Are you thinking about suicide.”

- This communicates you are open about speaking about suicide in a supportive, non-judgemental manner.

- Be there, whether this is being physically present, speaking on the phone, or showing support for an individual.

- Actively listen to the individual to understand what they are thinking and feeling.

- Keep them safe

- If possible reduce an individual’s access to lethal means or places.

- Help them connect with professional and community resources and services.

- Ask the individual how you can support them in accessing help from loved ones or mental health professionals.

- Follow-up

- After connecting an individual with immediate support, follow-up to see how they’re doing.

- Ask the question, “Are you thinking about suicide.”

- Emergency Response31

- To receive support from a trained counselor, call, text, or chat the 988 suicide and crisis lifeline.

- Call 911 immediately if …

- A person has a serious injury that requires medical attention.

- A person discloses they have taken substances in an attempt to end their life.

- A person is unresponsive.

Utilizing Real-time Medication Adherence Monitoring to Support Pro-Active Intervention

A reported 24 to 28% of suicide victims are non-adherent to their medications in the month before their passing.13 While existing adherence measures, such as pill counts and e-diaries, provide retrospective accounts of patient adherence, they are subject to social and desirability biases which may cause individuals to overreport their true adherence in journals or dump their medications to appear adherent.32

Employing real-time adherence monitoring measures is essential for identifying non-adherence patterns immediately. For those with an elevated risk, or prior history of suicidal ideations or behaviors, this monitoring could allow providers to determine patient’s at risk in real time, allowing for pro-active outreach from healthcare providers to offer the necessary support and resources.

Providing Support and Increasing Accessibility for those of Low Socioeconomic Status

For those of lower socioeconomic status – housing instability, reduced household financial security, and lack of social connection via unemployment or loss of employment – can all increase the risk of suicide.33 The CDC lists a series of strategies to strengthen economic supports and promote healthy social connections to address these challenges.33 Services such as supplemental nutrition assistance programs (SNAP), social security, and unemployment insurance are available to help those in need of financial support.33 Meanwhile, various services offer assistance to individuals in need of stable housing, like Housing First, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and the Veterans Affairs Programs for Veterans Without Homes.33 Recommendations for strengthening social support include engaging community members in shared activities and facilitating healthy peer connections within communities.33

Notably, low socioeconomic status itself can serve as a barrier to seeking help, particularly if individuals are unable to afford the costs associated with accessing necessary mental health support and services.33 Ensuring that all health insurance policies, including both private and public, cover mental health conditions is critical for expanding accessibility and ensuring individuals receive support, regardless of their economic status.33

Expanding and Improving Resources

For those residing in rural communities, it may be increasingly challenging for them to access the appropriate mental health services.25 Lack of public transportation services, expenses associated with transportation and time off, less opportunities for social connection, increased access to lethal means, and stigma surrounding seeking mental health services, can all prevent rural residents from accessing necessary care.34

As a result, increasing the availability of resources, reducing public stigma, and expanding accessibility to care is essential for ensuring individuals with suicidal ideation have the necessary resources in place to pro-actively seek support.34 Improving public health messaging regarding how to obtain mental health care, such as via telehealth of crisis lines, and disseminating free resources, is essential in ensuring rural communities are equipped with the awareness of existing resources and knowledge to utilize them.36 Moreover, encouraging individuals at risk for suicide to maintain social connectedness, whether this be through virtual communications, phone calls, or engaging in community events, can also help to reduce individuals’ risk.35

Given the stigma associated with mental health, individuals in rural communities with small population sizes may find it more challenging to maintain their privacy and anonymity.36 Telehealth services, that enable patients to access care from their own homes, in addition to increasing mental health education campaigns, offer potential solutions.36

Culturally-Competent Approaches for Suicide Prevention

Culture can have a significant influence on an individual’s likelihood of seeking suicide prevention resources. In order to develop effective suicide prevention strategies, respecting and responding to group’s beliefs, practices, and cultural needs and preferences is vital. Recommendations include:

- Continuing to research and understand the influence of culture on mental health and suicide.37

- Ensuring teams include diverse representation of cultures throughout planning, implementation, and evaluation to develop a collaborative, effective solution.37

- Tailoring information and resources to reflect cultural values, beliefs, and language whenever possible.37

- Facilitating an open-dialogue with members of different cultures to respect and understand their preferences.37

- Partnering with community organizations and leaders to increase trust in proposed resources and services.37

Suicide Prevention Month serves to remind us that talking about suicide is not harmful, but silence is.40 By raising awareness, spreading hope, and engaging in meaningful action, we can help break the stigma, support those who are struggling, and create a society where seeking help signals strength – not weakness. Together, we can save lives by engaging in open conversations, connecting individuals to resources, and showing compassion to those struggling.

References

1 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2025, August 11). Suicide prevention awareness month digital toolkit. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved August 28, 2025, from https://www.samhsa.gov/about/digital-toolkits/suicide-prevention-month

2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025, March 26). Facts about suicide. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/index.html

3 Peterson, C., Haileyesus, T., & Stone, D. M. (2024). Economic cost of US suicide and nonfatal self-harm. American journal of preventive medicine, 67(1), 129-133.

4 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025, March 26). Suicide data and statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/data.html

5 Cleary, A., Griffith, D. M., Oliffe, J. L., & Rice, S. (2023). Editorial: Men, mental health, and suicide. Frontiers in sociology, 7, 1123319. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2022.1123319

6 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Health disparities in suicide. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/disparities/index.html

7 National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2013, May 23). Suicide rates rise significantly amongst baby boomers, study finds. National Alliance on Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/nami-news/suicide-rates-rise-significantly-amongst-baby-boomers-study-finds/

8 Oyesanya, M., Lopez-Morinigo, J., & Dutta, R. (2015). Systematic review of suicide in economic recession. World journal of psychiatry, 5(2), 243–254. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v5.i2.243

9 Indian Health Service. (2023, March). Behavioral health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/behavioralhealth/

10 ATrain Education. (n.d.). 3. Suicide, race, and ethnicity. ATrain Education. https://www.atrainceu.com/content/3-suicide-race-and-ethnicity-0

11 American Addiction Centers. (2025, March 26). Suicide among veterans. American Addiction Centers. https://americanaddictioncenters.org/veterans/suicide-among-veterans

12 Casant, J., & Helbich, M. (2022). Inequalities of Suicide Mortality across Urban and Rural Areas: A Literature Review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(5), 2669. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052669

13 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2024, May 1). Suicide and mental health challenges in the construction industry. https://www.nationalacademies.org/news/2024/05/suicide-and-mental-health-challenges-in-the-construction-industry

14 Wyllie JM, Robb KA, Sandford D, Etherson ME, Belkadi N, O’Connor RC. Suicide-related stigma and its relationship with help-seeking, mental health, suicidality and grief: scoping review. BJPsych Open. 2025;11(2):e60. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2024.857

15 Motillon-Toudic, C., Walter, M., Séguin, M., Carrier, J. D., Berrouiguet, S., & Lemey, C. (2022). Social isolation and suicide risk: Literature review and perspectives. European psychiatry : the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 65(1), e65. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.2320

16 Silva, C., McGovern, C., Gomez, S., Beale, E., Overholser, J., & Ridley, J. (2023). Can I count on you? Social support, depression and suicide risk. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 30(6), 1407-1415.

17 Kupferberg, A., & Hasler, G. (2023). The social cost of depression: Investigating the impact of impaired social emotion regulation, social cognition, and interpersonal behavior on social functioning. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 14, 100631.

18 Arnone, D., Karmegam, S. R., Östlundh, L., Alkhyeli, F., Alhammadi, L., Alhammadi, S., … & Selvaraj, S. (2024). Risk of suicidal behavior in patients with major depression and bipolar disorder–a systematic review and meta-analysis of registry-based studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 159, 105594.

19 Kupferberg, A., & Hasler, G. (2023). The social cost of depression: Investigating the impact of impaired social emotion regulation, social cognition, and interpersonal behavior on social functioning. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 14, 100631.

20 Goldsmith, S. K., Pellmar, T. C., Kleinman, A. M., & Bunney, W. E. (Eds.). (2002). Barriers to effective treatment and intervention. In Reducing suicide: A national imperative (pp. 167–200). National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10398

21 National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2022, August). Risk of suicide. https://www.nami.org/about-mental-illness/common-with-mental-illness/risk-of-suicide/

22 Stack, S. (2021). Contributing factors to suicide: Political, social, cultural and economic. Preventive medicine, 152, 106498.

23 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, October 17). Suicide risk is tied to local economic and social conditions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/prevent-suicide/index.html

24 Agape Behavioral Healthcare. (2025, April 9). How much does inpatient mental health treatment cost? https://agapebhc.com/how-much-does-inpatient-mental-health-treatment-cost/

25 Vlasak, Rachael M., “Barriers to Help-Seeking Behavior for Individuals with Suicidal Ideations & Previous Suicide Attempts” (2023). Counselor Education Capstones. 185. https://openriver.winona.edu/counseloreducationcapstones/185

26 Eskin, M., Tran, U. S., Carta, M. G., Poyrazli, S., Flood, C., Mechri, A., Shaheen, A., Janghorbani, M., Khader, Y., Yoshimasu, K., Sun, J. M., Kujan, O., Abuidhail, J., Aidoudi, K., Bakhshi, S., Harlak, H., Moro, M. F., Phillips, L., Hamdan, M., Abuderman, A., … Voracek, M. (2020). Is Individualism Suicidogenic? Findings From a Multinational Study of Young Adults From 12 Countries. Frontiers in psychiatry, 11, 259. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00259

27 Gearing, R. E., & Alonzo, D. (2018). Religion and suicide: New findings. Journal of religion and health, 57(6), 2478-2499.

28 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2023, April). Mental health: Get the facts. https://www.samhsa.gov/mental-health/what-is-mental-health/facts

29 Fuller, Kristen. (2020, September 30). 5 common myths about suicide debunked. National Alliance on Mental Illness. https://www.nami.org/stigma/5-common-myths-about-suicide-debunked/

30 Barber, C. (n.d.) Means matter: Suicide, guns, and public health. Harvard: School of Public Health. https://hsph.harvard.edu/research/means-matter/

31 National Institute of Mental Health. (2024, August). 5 action steps to help someone having thoughts of suicide. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/5-action-steps-to-help-someone-having-thoughts-of-suicide

32 Eliasson, L., Clifford, S., Mulick, A., Jackson, C., & Vrijens, B. (2020). How the EMERGE guideline on medication adherence can improve the quality of clinical trials. British journal of clinical pharmacology, 86(4), 687-697.

33 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, June 4). Suicide prevention resource for action. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/resources/prevention.html

34 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, July 24). Suicide prevention: Rural policy brief. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/rural-health/php/policy-briefs/suicide-policy-brief.html

35 Monteith, L. L., Holliday, R., Brown, T. L., Brenner, L. A., & Mohatt, N. V. (2021). Preventing Suicide in Rural Communities During the COVID-19 Pandemic. The Journal of rural health : official journal of the American Rural Health Association and the National Rural Health Care Association, 37(1), 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12448

36 Rural Health Information Hub. (2025, March 17). Mental health stigma in rural communities. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/mental-health/4/stigma.

37 Suicide Prevention Resource Center. (n.d.). Culturally competent approaches. https://sprc.org/keys-to-success/culturally-competent-approaches/